The prairie states are filled with automobile collections calling themselves museums and debris-filled barns devoted to ancient farm implements. There are museums dedicated to barbed wire. I passed a small billboard, hiding in a windbreak of trees, announcing the Kansas Motorcycle Museum. When I saw another motorcycle turn down a side road, toward Marquette, I figured what the hey.

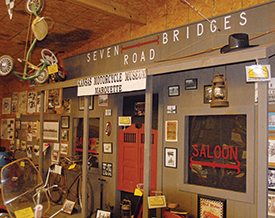

Marquette could be a model for the plastic towns that adorn train sets. Three blocks of tidy restored brick and stone buildings—the relic of a once prosperous town. Marquette once boasted an opera house, built in 1886—a building so grand it occupied a whole block. A one-room white brick schoolhouse, relocated from another town, served as a school museum. At the end of the last block (Washington and Third streets), occupying two adjacent storefronts, stood the Kansas Motorcycle Museum. A half-dozen Harleys nuzzled the sidewalk.

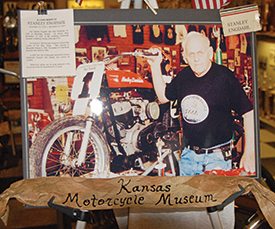

I parked on the north side, beneath a wall mural painted by students at a nearby Christian college. An old Harley dirt track racer piloted by Stan “The Man” Engdahl seemed to leap out of the frame. On the back, a pert brunette wrapped her arms around the driver’s waist. The backdrop indicated a crossroads of State Routes 141 and 4. For most of the century, I would learn, 4 and 141 were the main roads out of town. The intersection depicted in the mural was near the reservoir, where young lovers fought the summer heat, close to the farm where Engdahl was born.

I walked inside to be greeted by a spry silver-haired lady, whose reedy voice was woven from loose skeins of air and smoke. She was the girl on the bike, 50 years later, LaVona Engdahl. She pointed to a jigsaw puzzle showing a curled up cat with a sign: “Warning: I don’t do mornings.”

“That’s me. I am not a morning person,” she said.

She waved me into the first showroom. Along one wall, enshrined in a glass case, were some of the 600 trophies her husband won mucking around on motorcycles. As a teenager, he’d built a dirt track on the family farm. Won his first race in 1944. After serving in the military, he got serious. In his 40s, he won the national scrambles championship five times. He was Kansas State Champion 16 times. He won one race with a broken leg taped to a 2-by-4 splint. In the center of the showroom was the 1957 Harley-Davidson 750 K model on which he’d dominated the prairie states. Engdahl ran a motorcycle shop for years, and also served the people of Marquette for 30 as chief of the volunteer fire department. He died in 2007 after collapsing at a house fire.

In 2003, the town had embarked on an ambitious plan to restore the three-block downtown area. Buildings were painted in their original color. The opera house became home to small shops. And the storefront on the corner of Washington and Third became the Kansas Motorcycle Museum, something for Stan and LaVona to do as they aged. Some 21,000 riders have passed through the museum. It is a gathering place for poker runs. A side eddy in the stream of bikes heading west on Interstate 70.

Expanded to two showrooms, the museum houses over 100 bikes, some rare, some whimsical. Mike Bahnmaier, a man with two Harley dealerships in Kansas, loaned the museum a stunning collection of vintage motorcycles. I wandered the black-and-white checkerboard floor, admiring a 1906 Thor Single Cylinder Racer, then a 1914 Yale 2-speed twin (both still bearing bicycle pedals and chains as backup).

There was a 1916 Indian 8-valve boardtrack racer, a 1922 Harley and a 1926 Excelsior Super X. I imagined screaming engines, splintered tracks, wide-eyed fans. A 1927 Indian bore a tag identifying it as a Wall of Death Bike.

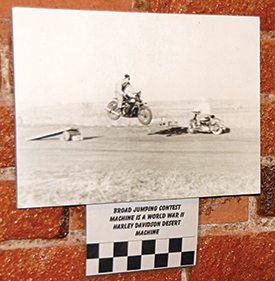

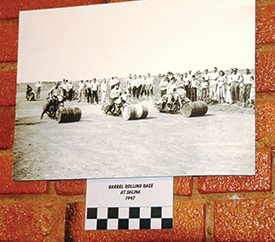

Now they sat quietly, dripping oil into tin pie plates. Signs carried a plea: Eyeballs don’t leave fingerprints. The bikes were immaculate, the product of careful restoration. The exposed walls were covered with photos showing the role of motorcycles in mid-century Kansas. A “stunter” standing between two bikes piloted by the Marquette Thrill Riders team. A solo rider climbing down from a ride standing on his seat. A bike in mid-air, propelled off a short ramp in a broad-jump competition. Hotshoe riders planting a foot as they careen around a dirt track. Three riders lined up nose to oil drums in something called the Salinas Barrel Rolling Race. Let Valentino Rossi try that.

I thought of the difference between this homegrown sense of fun—soldiers returning from war restless, bored and finding fun in the mechanical possibilities of Harleys. On the West Coast, those restless men gave us the Hell’s Angels and Hollister. Here in the heartland, we ended up with thrill seekers, steel-shoe competitors, fun and true love.

I saw a photo of Stan and LaVona on their wedding day, seated on a Harley outside of a trailer. Yes, the museum has motorcycles. But something more.

Morning was hours behind. I found LaVona working on another jigsaw puzzle—an attic overflowing with interesting objects, wooden floorboards—the kind of puzzle that has a useful clue in every piece. “That’s my attic,“ she said, “my life. Every Christmas I get a new jigsaw puzzle.”

I asked if I could take her picture. We flirted. I went outside and looked at the girl on the bike in the mural. I imagined what she must have felt like the first time she felt the wind in her hair, and how that feeling lasted a lifetime.

LaVona passed away at the end of 2013.

(This article Dreams on the Prairie was published in the December 2014 issue of Rider magazine.)