You’ve got to love Thomas Wolfe, the truly great American writer who died at 38 in 1938, but not before he passionately put thousands of words to the beauty and sadness of everyday life, feelings most of us have but don’t have the God-given talent to express. You can’t go home again, he lamented. In the true sense he was right. But I’m talking ephemerally here about Pam’s grandparents, Francis Leroy and Mary Pearl Bruce, their ramshackle farmhouse and an old apple tree that still bears cold red sugar pills in October’s first frost. The house and the tree are located on a hill in Tekoa, Washington, in a place suffused with the past called The Palouse, where deep volcanic loess birthed a 2,000-square-mile undulating sea of grass 30 million years ago that rolled forever just like the ripening wheat does now. Pam was born there March 29, 1947, in a nearby midwife’s home, which is still there, too.

It seemed like a good reason, like a good place to ride. For me, riding home again was out of the question. I’m from L.A. My home is done, gone, extinct, outtathere and otherwise as strange and cold to me now as a crater on the moon. I knew from a previous reunion with Pam’s relatives that the Palouse is still very much intact, that Tekoa and a dozen other small townships tucked into the creases of the green hills are images from a Norman Rockwell painting, that endless waves of grain shimmer in a staggering panorama of light and shadow and recall the anthem that celebrates the beauty of America.

I told Pam, dear, let’s go home again, to your home, to the Palouse. Call Aunt Tootsie. Tell her and the rest of the Bruce mishpookah, as we say here in Big Valley, to get the meatloaf in the oven. We’re on our way to Spokane with plans to rent a Harley-Davidson and ride to Tekoa and environs and connect with your Grandpa and Grandma Bruce. I know they’ve been gone for decades but trust me—we’re going to cruise their homeland with alacrity, and remember their life and times. Advise Tootsie I can tell from the old sepia photograph from the ’30s of the two of them in the gilded frame she sent me that I’m pretty sure I would have loved Grandpa and Grandma, too. He in those grimy workaday bib overalls and his Jack London tousled hair and she without a stitch of makeup in that shortsleeve muted print dress with a sweetly feminine touch of lace at the breast pockets and at that ladylike neckline and with her left hand resting tenderly on his right shoulder and their wonderful honest expressions that say, Hey world, give us all you got, we can take it. Yep, I’m pretty sure I would have loved them, too. A Harley-Davidson motorcycle seemed right for this project. The internationally famous Spokane photographer I cajoled into this project to back up my meager skills with my ancient (horrors!) non-digital Nikon, a supremely creative lensman by the name of Dominic Bonuccelli, rides a Suzuki.

There’s a huge Einar Petersen oil that looms above the fireplace in the grand lobby of the centurial Davenport Hotel in downtown Spokane, a rather dramatic epic mural of Columbus’ ships, the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria negotiating a wild running sea. I wondered why I was so drawn to it until we rode south into the heart of the Palouse on Highway 27 and I saw that storm-tossed ocean again as a bounding landscape, the sculpture of an Ice Age flood of Genesis scale that involved 500 cubic miles of water suddenly breaking through an ice dam in what would be called Montana 17,000 years later. This is called understanding the land, Scarlet, the only thing that lasts. Since we are here for what amounts to be five minutes you might as well navigate an elongated series of sweet soulful corners on your Ultra Classic Electra Glide and fly through April emerald waves of burgeoning wheat and connect with, well, there’s no other word for it, creation. The stuff that went down before we arrived on this incredibly diverse fascinating planet is important. The stuff lends perspective. Is it just me or do Disneyland and the Super Bowl and Michael Jackson and Arnold’s Hummer and Martha’s souffle and your brand-new high-resolution plasma television matter a whit in the grand scheme of things?

I’m fighting the urge to believe I was born too late. I wish I could have been there in Tekoa the night that Grandpa Bruce, a boxer in the Marines in 1917, this tungsten-tough guy at 140 pounds, reluctantly kicked some ass in the bar and then drove bullyboy to the hospital and then went back to the bar to help clean things up. Was this not a gentleman? At Grandpa and Grandma’s place in Tekoa, now long deserted, sadly the barn long gone, I ask Pam, please dear, go sit under the old apple tree out back where Grandpa went to sleep forever in 1974 and then tell me a story. She says, When I was quite a little girl, maybe four, Grandpa asked me to bring him some matches so he could do some welding on the plow. Somehow the matches ignited and my whole sleeve went afire. Grandpa heard me scream and there he was in a millisecond to push my arm into the snow.

We ride to Goldenrod Cemetery located in a windy copse of trees on a round hill high above Tekoa so Pam can pay her respects at Granda and Grandpa’s grave. Grandma died in 1967 after a life that would have snuffed a lesser woman decades earlier. Shot by her unhinged father in 1935, diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1939, her 10-year-old son killed in a shooting accident in 1942, run over by a grain truck in 1954. And I bitch when a sprinkler goes on the fritz. Cousin Cookie tells my favorite Grandma story: “When I was four Grandma picked me up in the old Ford with Frieda, her Nez Perce woman friend, who knew where the best huckleberries were to be picked. Well, Frieda stank like old road kill in July; she bathed rarely, let us say. Grandma had the windows down but I was dying in the back seat. Then I saw Grandma’s eyes in the rearview mirror. Her expression said, I love and respect this Indian woman and if you let on one smidgen of your discomfort I’m going to tan your hide dark brown.”

Pam’s Aunt Tootsie, Grandma and Grandpa’s youngest daughter (her real name is Virginia but Grandpa always called her Tootsie), is 70. She is an attractive zaftig woman with a big heart, tested plenty by life’s usual tragedies over the years. There’s a sign over her stove that reads “The Only Reason There’s A Kitchen Here Is Because It Came With The House.” Believe me, you do not even try to BS this woman. She has two dreams left: One, to go skydiving and two, to ride on a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. I always consider it nothing short of miraculous when I can make a woman happy.

Of course you can ride home again if you are fortunate enough to be born and raised in the Palouse, because the clock stopped here, or at least slowed way down, a long time ago. And the whopping slap-in-the-face irony is that the cause is called progress. When motorized farm machinery began to replace the horse-powered variety, fewer people were needed to work the land. Population drained, development in many local towns and communities ceased and so what we have here now is a tableau of western America to cruise that is unfettered by heavy traffic, crass commercialism and other unpleasant realities of the new world order.

You better plan a place to sleep, though, because motels in the Palouse are rare as hen’s teeth. We stayed in Tekoa at Jerry and Mary Heitt’s 100-yearold house, Touch O’ Country Bed and Breakfast, located in a lovely leafy neighborhood of the old hometown. Jerry was in the milk business and remembers delivering to Grandma and Grandpa Bruce’s farmstead 40 years ago, so there is great connection here as well, and Mary’s cinnamon rolls are world class.

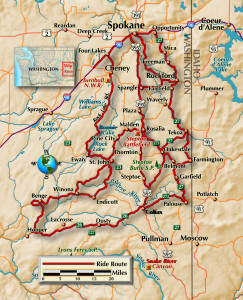

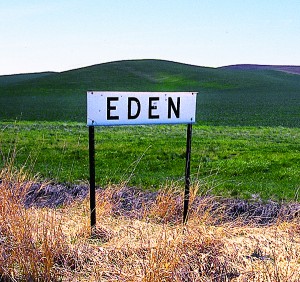

My intention is to ride every road in the Palouse, and we come close to pulling it off. Scenes from our moto tour unwind in an unforgettable series of meaningful moments. Fried oysters at the Harvest Moon in Rockford, where I chat with one of the local citizens, a Harley rider, who tells me he escaped from the city 10 years ago and it was the second best thing that ever happened to him (the first best thing being the Harley and he said so right in front of his wife). An historic gray abandoned gas station in Farmington that fueled an era of Model T’s. A stunning 360-degree hundreds-of-miles-in-every-direction view of the seemingly infinite carpet of the Palouse from atop the 3,612-foot summit of Steptoe Butte, a quartzite mountain that has survived eons of erosion, and once the vertiginous site of a hotel called The Cashup, now gone with the wind. A sign along the tracks at a railroad shed near Garfield that reads simply in block letters “Eden” against a sprawling backdrop of green hills draped with the fecundity of burgeoning grain. A shadow of motorcycle and rider on a weathered barnwood wall at sunset in the region’s namesake town of Palouse. Palpable history on the windswept knoll of Steptoe Battlefield in Rosalia, where in 1858 Colonel E.J. Steptoe and his command of 159 cavalrymen were routed by an allied band of Spokane, Palouse and Coeur D’Alene, a rare victory for the tribes. Getting lost on the road to the lonely abbreviated hamlet of Ewan and ending up Electra Gliding through a grain field. The windfretted surface of deep, mysterious Rock Lake, said in Indian lore to be an evil place of strange sucking currents according to Cousin Cookie, where five fishermen, the church pastor and four young men, and even once a derailed train, disappeared forever. (Cookie, by the way, is a specialist in family counseling for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Would you say Grandma Bruce’s Frieda lesson took?)

The symbolic perfection of giant 10-story General Mills grain elevators looming against a pale blue sky high above and behind and overbearing old storefronts on Main Street in St. John, including the Rialto, the favored local watering hole, where the ladies there put up with our Harleyish aggrandizing like, well, ladies. The barns of the Palouse, the artistic architectural perfection of function dictating form, the grand working buildings from the horse-drawn era that symbolize shelter and harvest, warmth and honest effort wedded to that most ancient of human activities, the growth of the soil. I wondered why I’ve often thought of barns as cathedrals without a superfluous line and then I walked inside the big round barn on Highway 23 east of Ewan and looked up at the great dome and remembered that twice-repeated line in T.S. Eliot’s haunting poem: “In the room the women come and go talking of Michelangelo.”

So much to see, so little time. It takes me all week to finally reach Nona Hengen on the phone in Spangle. I know of her only by her reputation as an accomplished artist and writer, especially as a chronicler of regional history and culture in the third edition of her massive 900-page tome, Gateway To The Palouse, which is as telling a portrait of American history as I’ve ever read. Get this from the dust jacket: “William Spangle, Palouse pioneer, has experienced the brutality of war during Sherman’s March to the Sea, despair as a Confederate prisoner, and sorrow at the death of his president, Abraham Lincoln, whose hand he shook when he was liberated from Libby Prison in Richmond when the Confederate Capitol fell.” You don’t think this whole country of ours is as connected as chainlinks?

Nona’s ancestral family farmhouse outside of town also serves as a gallery of her prolific talent. When she shows us in and we view her large mural of Palouse Falls and the magnificent canyon into which it spills, the handiwork of the raging Biblical Ice Age Flood, and she says, “Surely you rode there, didn’t you?” I realize we’ve managed to avoid one of the region’s major scenic exclamation points. It’s OK. It’s a compelling reason to return soon, to ride home again, maybe just before harvest time when amber waves of grain are rolling across the land. Aunt Tootsie said, as we were departing, struggling not to weep as she said it to me, that Grandma Bruce often reminded her to live every day like it was the last day.

(This article You Can Ride Home Again: Seeing America in the Palouse was published in the November 2005 issue of Rider magazine.)

|

|

|

|