(The article Norm and Me was published in the January 2010 issue of Rider Magazine.)

Story and photos by Bill Heald

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from traveling many, many miles by motorcycle, it’s that it is a very visual medium. True, the smell of the flowers, bakeries and the compost piles you pass as you ride along, and the feel of the temperature dropping as you go into a valley are all an integral part of the experience. The sounds of the passing environment can’t be ignored either, unless you’re running with a pack of straight-piped cruisers.

But the eyes get the most sumptuous feast as we travel, and when I strap on my helmet and load up the saddlebags for a two-wheeled excursion, my visual sense goes into a very specialized mode. As you need to keep your attention focused on the road for survival’s sake, you really can’t peer extensively at the passing flora, fauna and Things of Man the way you’re able to do when staring out of a train window. What I do is take visual “snapshots” of the passing world, and after the trip you’re about to read about, I have learned to capture such moments with much greater clarity. Thanks to seeing things through the eyes of a master observer, these portraits of the ride get etched in my mind in a much more meaningful way.

Norman Rockwell was one of America’s most famous artists and illustrators, and knew a thing or two about visual snapshots. Best known for his iconic The Saturday Evening Post covers, his peerless mastery of realism and his ability to convey a uniquely American view of everyday life made him famous all over the world.

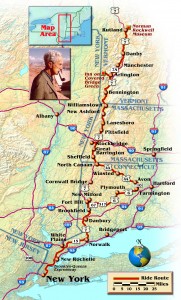

I’ve always been curious about Rockwell because, while he was undoubtedly an American treasure, he certainly had his critics who thought he often painted the world through rose-colored glasses. Since I’m basically a tank half-empty kind of guy these days, I was intrigued by this optimistic outlook that is clearly a bit different from mine. In reading his biography, I learned that Rockwell lived his life in three really picturesque Northeastern locations that unquestionably shaped how he viewed things. Clearly, in order to get a feel for how he saw and reproduced the world around him, I had to visit them all on (what else?) a Triumph Rocket III Touring. Why the Big Triple? Well, Rock-et and Rock-well seem to go together, and I more than once told folks it was actually a Rockwell III Touring that I was riding.

The tale begins in a town called the Mighty Macintosh, or as it is occasionally known, the Big Apple. Norman Rockwell was born in a brownstone on the Upper West side of Manhattan, which today is still a pretty charming neighborhood where you can park your Rocket III with ease and stroll around. As Rockwell did not become nationally famous here (although he started illustrating Boys Life covers at the incredibly young age of 16), I therefore saddled up and headed toward nearby New Rochelle, where his professional career took off shortly after he migrated there in 1915. After a quick visit to my old apartment in Brooklyn (nostalgia overtook me for a moment), I used the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway to get me to the Hutchinson River Parkway, and you’ve never seen two such wildly contrary roadways. Where the B.Q.E. is a flow-challenged, often battered concrete goat path that tested both the Touring’s suspension and my backside’s compliance, the Hutchinson was on this sunny day a smooth, bucolic masterpiece of upscale motoring magnificence. This was the kind of road that I could see would help make a commute into The City more tolerable, especially on two wheels.

I rolled off the parkway and into a quiet, perfectly maintained neighborhood that looked remarkably (dare I say it?) picturesque. I parked in front of Rockwell’s former New Rochelle home, comfortably nestled in a community where he spent many happy and productive years. At the age of 22 he did his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post, and over the next 47 years he would do 320 more for this prestigious, and iconically American, publication. While Rock- well was most famous for these covers (that he produced in stunning oil paintings I got to see many of later), he was an incredibly prolific artist and illustrator who worked in many media and left behind a vast, fascinating body of work. Much was done here, but he took his second wife and three sons up to Vermont in 1939. Enough New Rochelle Rockwell reverie! It was clearly time for me to head north.

I got back on the Hutchinson River Parkway, which mystically turned into the Merritt Parkway (also known as Route 15) in Connecticut. As I motored north this route continued to be a very pleasant, winding trail that forbids truck traffic. Just past Norwalk I vectored west over to Route 7, also known as the Ethan Allen Highway, and a bizarre thing greeted Le Rocket and me as we trekked north. Just past Brookfield, I observed what I thought was either the Martian war machines from The War of the Worlds or some really bizarre-looking electrical towers. It was the latter, but through the blurred mosaic of my bug spattered visor (I was running next to the Norwalk River, quite popular with flying insects), I’d swear these things were moving.

This bug-induced “art” was instrumental in putting me in a Rockwell state of mind, because once I wiped off my visor I could again see the world around my Triumphant perch with crystal clarity. I recalled how much of Norman’s work expressed incredibly sharp detail; of seeing the intimate points of humanity that others may miss. “Without thinking too much about it in specific terms,” he once said, “I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed.”

This critical aspect of Rockwell’s work changed how I saw things as I rode along on this journey. Farther up on Route 7, I encountered some wicked-nasty construction; the kind that makes you cook in the sun and brutally taxes your clutch hand. Yet I actually found the putt-putting in traffic allowed me to observe the faces of road workers as they rebuilt and expanded the road, and I saw their sweat and effort and concentration in a Rockwell way that I would have missed before. I was one who before did not notice, and now I was noticing.

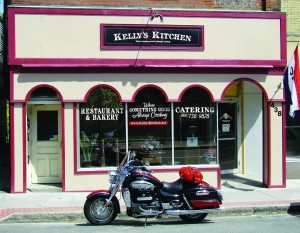

Freedom from traffic congestion came when I headed east on Route 67, and the ride that followed was nothing short of stellar. Parts of this smooth, winding empty route with the odd scenic overlook reminded me just a bit of the Blue Ridge Parkway, with a stronger New England flavor of course. As I headed east on Route 317 toward central Connecticut the antique stores gained in frequency, which was a sight I was to see all through this trip through Rockwell’s rural America. There’s lots of cool old stuff in this region of the country where the American lifestyle as we know it first got off the ground.

It was time to pick up the pace, so I throttled up the big Rocket and followed Route 6, Route 10 and ultimately Route 44 heading northwest. A very late lunch in Winsted, pie in North Canaan and bam! I was on Route 7 heading into Massachusetts. I call this part of this roadway the Rockwell Parkway, because it links major Norman sites together and has tributaries (like Route 7A in Vermont) that show that 19th- and 20th-century small-town America is still around in the 21st century.

In Stockbridge, Massachusetts, we find the largest and grandest of the Rockwell museums, for in 1953 this is the final town where he settled, living and working here until his death in 1978. I broke the chronology of the trip at this point (he lived in Vermont in between New Rochelle and here), as I really wanted to see this excellent facility and take the audio tour right away. This is a comprehensive trip through his life and times, and you get to see a substantial volume of his work in full oil-painted glory and learn how he worked and found his subject matter. His beautiful Stockbridge studio has been moved to the museum site, and the main street of the town itself still looks much as he captured it in the past. Rockwell’s models and locations typically came from right around him, using the neighbors and structures that he regularly visited.

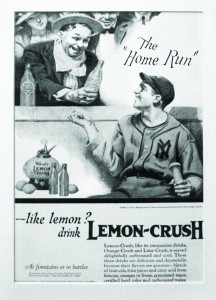

After staying in Pittsfield, I rolled north (and back in time, in terms of Rockwell’s life) on Route 7 into Vermont and the charming little town of Arnold. Rockwell lived here from ’39 until ’53, and west of town Julia and Clint Dicken’s Inn on the Covered Bridge Green is found close to the babbling Batten Kill River (which is famed for its fly fishing). On their property is a studio Rockwell built in 1943 to replace one that burned down earlier, and the Dickens now let folks stay there as part of their bed-and-breakfast operation. In Arlington there’s a small but (I’m told) excellent Rockwell museum, but it was closed when I was there so I headed north to Rutland, where I knew another Rockwell collection was waiting to be examined. I stayed on Route 7A as long as I could, cruising through the charming town of Manchester and arriving at the Rutland Rockwell Museum just after enduring a rather robust thunderstorm that battered the Rocket with rain drops the size of small asteroids. This museum was a pleasant surprise, for it has an absolutely vast collection of Rockwell’s work including illustrations you don’t see very often. These include movie posters, advertisements and tons of magazine article illustrations all displayed chronologically. This is a must-see for Rockwell fans, and their gift shop is likewise vast and interesting.

After a pleasant stay in Rutland it was time to roll back south toward Manhattan, and as I rolled away from a gas station I watched a strange character standing by the intersection with a sign he flashed at passersby. His sign said, “I knew about the Terrorist Attacks,” and his baseball cap, aviator Ray-Bans, perfectly laundered shirt and khaki pants and newish New Balance running shoes gave him the bizarre aspect of a CIA spook that had, well, changed course in life. I couldn’t help but notice as I rolled on the power and blasted out of Rutland that I see the world with far greater detail now, for I absorbed this singular individual’s aspects as he stood on the corner with a quick, passing glance. I have Norman Rockwell to thank for this newfound vision, and can’t recommend a ride on the trail of this amazing American artist highly enough.