Gazing from behind small, wire-framed spectacles and fingering a pointed beard, he was right off the set of a Burl Ives movie. Driving a relic of a pickup truck nearly his own age, he cruised along indifferent to cars traveling 20 mph faster. Like me, he appeared to be on his way to Los Angeles, and there were still 30 miles to go.

My loaded motorcycle eased by, the Ohio license plate apparently breaking the highway’s spell. Catching up alongside, he nodded warmly, then with a long sweeping motion pulled off his straw hat and proclaimed, “Welcome to California.” With that, he slowed and soon disappeared in my mirrors.

That was four decades ago and now I was planning another trip, one that would again take me to L.A. Over the years I’d found what I considered some of the finest riding highways in the U.S., and at 65 years of age I wanted another crack at them. But this trip would be different.

For all of those years, my trips west from my central Ohio home had taken me first to Denver, where my best friend Ed Burchard lived. We’d been in Vietnam together and he was the best man at my wedding. The trip to Ed’s had always been a prelude of sorts for the remainder of my adventure. But this year Denver would be my last stop. There were highways to be ridden before I got there, fellow riders to meet and share stories with along the way.

U.S. Route 2, my original “favorite highway,” was my first destination. Years ago I’d ridden it from Washington state heading east into Minnesota. All those years ago it had stood out. Little seemed to hinder my progress as I rode past miles of wheat fields and through the many small towns. Route 2 seemed to stretch on forever, this long thin line across northern America.

This year it was again a special ride, but after 40 years had become the local freeway, four lanes of easy travel from one place to another. I decided to look for adventure on the less traveled two-lane roads I prefer. A few miles to the south I found the perfect road, one that would take me all the way to Montana and the famous Beartooth Highway. Long regarded as one of the finest motorcycling highways in America, it calls people like me back again and again. But I’d picked the wrong time to be traveling in this part of the country. The tight switchbacks of the Beartooth were slowed by rain, and to experience the ride as one should I would have to return someday.

From there it was on to Glacier National Park and its Going to the Sun Road, a Mecca for anyone on two wheels. Around every turn the scenery changed, revealing even more jagged peaks. The parking lot on the Continental Divide at Logan Pass is clogged for a reason.

Days later I found myself on California’s PCH, the Pacific Coast Highway, a magnet for anyone on two wheels. For an Ohio flatlander the true draw to the West Coast is riding along the Pacific Ocean. Here the highway and the coastline mesh, forming a bond; the line of pavement acting as an artist’s flowing line separating the primal Pacific from the soft beaches and harsh cliffs. This is paradise for anyone on two wheels. On one side is the largest body of water on this earth and on the other a barrier intent on holding it in place. The result of that struggle is some of the most coveted real estate in America.

After all of the highways I’d been on and how straight most were, my tires had worn a bit flat in the middle. This road, and the many other crazy mountain roads I traveled in California, took care of that problem. When I eventually headed east my tires had regained their rounded form.

Yosemite, what I consider the most beautiful of America’s national parks, was next. I don’t believe there’s any way to look at the park other than in a state of awe. With the road to Glacier Point, the beautiful ride through the valley and the ride over Tioga Pass, this is a special place.

As I rode through California I started to give more thought to where I was heading. Over all of the miles and no matter which direction I was headed, I was always aiming for Ed’s place. He’d grown up in California but Denver had been his home since our days in the service. On all of my visits we’d share the same tired war stories from years long past, with Ed’s boisterous laughter filling the air for half a city block. Always the contrary one, even though he had been born near Oakland, Ed had chosen to live in Bronco Country where his beloved Raiders were despised.

Once out of California the miles seemed to skip by. A 75-mph speed limit will do that. On the eastern edge of Arizona between Clifton and Alpine is a north-south stretch of highway once known as U.S. Route 666, the Devil’s Highway. The number was changed to U.S. Route 191 some years back, partly due to so many highway route signs being stolen. It’s known in many motorcycling circles as one of the finest stretches of roadway in the U.S.

From the south it first runs through a massive copper mine. If you’ve never been close to anything like it this is a must-see. But once beyond that the fun begins. This highway is not for the casual rider in a hurry; it’s a test of will and ability, particularly in the south. Treat it like a racetrack and you’ll be disappointed.

Later the highway opens up into a more tranquil place. I saw mountain goats and wild turkeys, and there were warning signs for elk. This is somewhere near a hundred miles of glory, truly a serious motorcycle rider’s paradise.

Thirty years earlier Ed had told me about a road he’d found in his four-wheel-drive truck, portions that were at best a logging trail. Today it’s called Utah State Route 12, aka A Journey Through Time Scenic Byway. For me it starts in Escalante, continuing through Boulder to Torrey. In reality this stretch is 60 miles of pure joy for anyone on two wheels.

Beginning just beyond Escalante, the highway drops quickly into what can only be called the most beautiful expanse of slickrock you can imagine. The colors, the nearly molten terrain, are what you might find on another planet. Allow for time, it’s hard to keep your eyes on the road with so much beauty around you.

From there it was up a bit and along the Hogback, the spine or ridge of the area, then up into the aspens. There’s little along the highway to remind you of civilization, and that’s one reason I keep going back. I find it magical.

There were other “fun” finds along the way. In Milwaukee I’d stopped by the Harley-Davidson Museum and watched the fantastic mechanical wings open over the city’s art museum. I visited Lambeau Field, and in Bemidji, Minnesota, I found my first Paul Bunyan. Then, later in my trip, a second in Klamath, California. In Montana, I stopped where Custer had last stood, and in Astoria, Oregon, found the Astoria Column. In Eureka, California, I admired the beautiful murals painted on the city’s buildings and in L.A., Dodger Stadium, a must-see for every baseball fan.

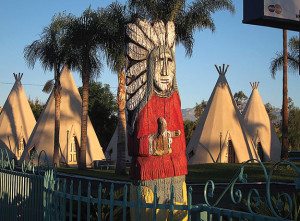

It seemed that at every other stop I’d find some welded recreation of a metal dinosaur. In Victorville I found the Route 66 Museum and from there I spent a night in one of the iconic structures from the Route 66 era, the Wigwam Motel in San Bernardino. Where else could you wake up in a teepee with nearby roosters welcoming the rising sun? Near San Diego I watched hang gliders set sail along the Pacific shoreline, and in Felicity, California, the Official Center of the World, gazed at our planet’s history in granite. This may have been the most unexpected find of my entire trip.

On Utah Route 12 I had saved the best till last. I’d had my fun. This was my favorite ride in decades. But after a night in Torrey, it was on to Denver and Ed, and this was no longer an adventure—it was now a trip of another nature, a serious commitment. I was going to say good-bye to my best friend at Ed’s memorial service, and there were still miles to ride.

Ed had passed some weeks earlier, so the pain of him being gone had subsided a bit. I arrived early at Fort Logan, the military cemetery in Denver. Stunning in its simplicity, its rolling acres and thousands of grave markers gently reflect the somber elegance of our military tradition. The weather people had claimed that it would be raining hard by noon and later the skies would really open up. I had reason to be concerned.

There’s nothing that can match the dignity of a military funeral. The USAF supplied two tech sergeants as an Honor Guard. They folded the American flag and with crisp precision presented it to Ed’s wife. Ed had told her the one thing he wanted at his funeral was a “flyover,” something reserved for military officers or dignitaries, not a one-term sergeant. But mid-way through the eulogy we were interrupted by two fighter jets screaming overhead. The thought of those two jets being there for Ed’s family still raises goose bumps. Ed had a way of always getting in the last word.

This was the perfect setting for those who loved Ed to say farewell. I stayed in Denver for another day to help with family matters and, after a few tears, was on my way home. There were still things to see but the adventure was over, and I don’t remember much from the days of riding that were in front of me.

It never rained that day. Thanks, Ed.

Rest in peace, my friend. Rest in peace.

|

|

|

|

This was a beautifully written and poignant article. I’m surprised no one has commented on it yet. You’ve managed to pack a powerful, life changing experience into a few paragraphs, Mr. Frick. Thank you for that.

I could also trace my previous path with him through parts near Escalante; it brought back memories from 20 years ago I took on a similar trek. It’s an incredible area of the Southwest and will leave an indelible mark on you if you’re lucky enough to experience it.