When winter drifts into North Texas, those of us who ride year-round seek more agreeable climates, yet never have to leave the state. Big Bend National Park, where the Rio Grande does a U-turn on the border between Mexico and Texas, is very attractive between November and April. During the summer months, ground temperatures there can be as high as 180 degrees Fahrenheit—no bueno. But except for the occasional winter storm, the barometer hangs around 20 percent humidity and daytime temperatures dwell in the 70s in Big Bend during late fall, winter and early spring.

Big Bend National Park contains over 800,000 acres of mountains, high desert and river environments. It is one of the least visited parks in the National Park System and is surrounded by vast ranch country that is principally inhabited by high-desert wild things. Throughout the larger Big Bend region, the roads are broad, the curves sweeping and the vistas immense, with virtually no traffic. Speed limits seem all but ignored, except in the park itself, where police exhibit an uncanny ability to appear out of nowhere just when the road begs for something more than 45 mph.

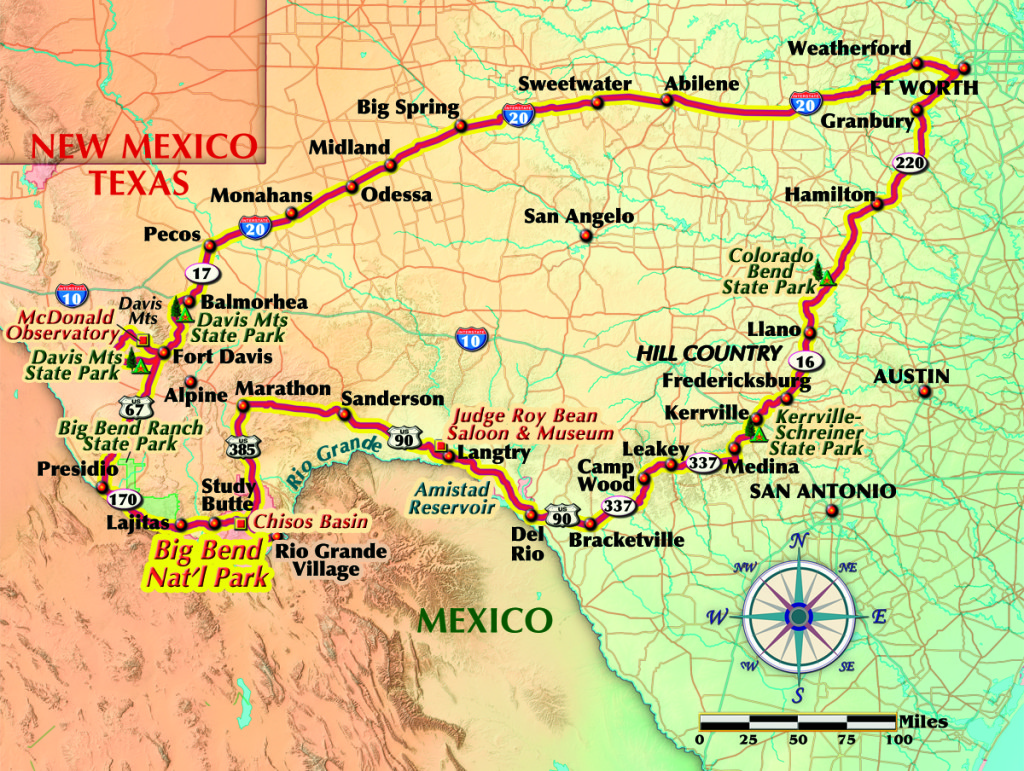

The journey to Big Bend is a major one for us. Our less-than-direct 600-mile route from Dallas/Fort Worth to that remote area of West Texas is curvaceous and seductive, passing through the stunning, limestone-riddled hill country west of Austin. Some of the roads along our route are especially popular with motorcyclists, like Farm to Market (FM) Route 51 south of Granbury, State Route 16 south of Kerrville and the renowned Twisted Sisters. Their twists and turns are fun and irresistible, but sometimes catch riders off-guard in the more challenging spots, places where small memorials of trinkets and motorcycle parts often haunt the roadsides.

On this ride we lunched in Llano along Route 16 at Cooper’s Bar-B-Que, turned west on FM Route 337 at Medina (one of the Twisted Sisters) and said a fond adieu to the hill country at Camp Wood. The Texas Pecos Trail Region, which consists of 22 West Texas counties and almost 35,000 square miles, beckons…real ranch country with great expanses that are vacant of corrals, barns, houses, lights or traffic…and lonely. Only an occasional glimpse of a Border Patrol vehicle, a solitary sentinel on a distant mesa, reminded us that we were not alone.

Though the official position is that the Texas border with Mexico has been closed at all but a few points of entry along the Rio Grande, the “border” is in fact a virtual reality. Brackettville is not an official entry point, but it was our overnight destination and close to the border. So we checked in at the security gate for Fort Clark Springs and found our rooms in the barracks, built in 1874. This frontier fort is a historic site converted into a recreation center and resort, and the barracks have been converted into a motel, relatively safe and secure, especially for unattended bikes.

The following morning, we picked up the Texas Pecos Trail (U.S. 90), which covers over 1,300 miles from San Antonio to the west and northwest, taking us toward the wilds of Big Bend. Del Rio, the last sizeable town on our route, disappeared in our wake. We crossed over the Amistad Reservoir, situated in both Texas and Mexico, then the Pecos River that feeds it. Barely noticeable alongside the road, the village of Langtry boasts the historic site of the bar where the famous “Hanging Judge” Roy Bean held court, with Boot Hill out back.

Pressing on, we rode as far as Marathon and checked in at the Gage Hotel around 3 p.m. It’s only 30 miles to the north entrance of Big Bend National Park on U.S. 385. We had plenty of time to ride to Rio Grande Village near the southeast boundary of the park before sunset and gaze upon the shining bluffs of the Sierra del Carmen range. We didn’t tarry because large wildlife abounds, especially after dark, and the margaritas and steaks prepared in the White Buffalo Bar at the Gage Hotel were calling our names.

Alfred Gage, a transplant from Vermont, built the Gage in the late 1920s. He needed a hotel and headquarters for his 500,000-acre ranch, which was accessible only by train or horseback over a long and desolate road. A Texas oilman bought the hotel in 1978, restored it to its former glory and added the bar, a health spa, a seven-acre garden and additional rooms around a courtyard near the pool.

Big Bend National Park also contains the northern portion of the Chihuahuan Desert along 118 miles of the Rio Grande. This remarkable convergence of desert with mountain and river ecosystems is one of only 250 areas in the world to be designated a “Biosphere Reserve” by UNESCO. It is vast and remote with few services. Gas is available in Marathon, one location in Big Bend National Park (not always open) and Study Butte, outside the western boundary of the park. Alpine, Texas, located over 100 miles to the north, boasts the nearest hospital. Personal safety is stressed in the park, and most folks who visit are encouraged to remember the common mantra regarding flora and fauna in this country: “If it don’t stick you, it’ll bite you.”

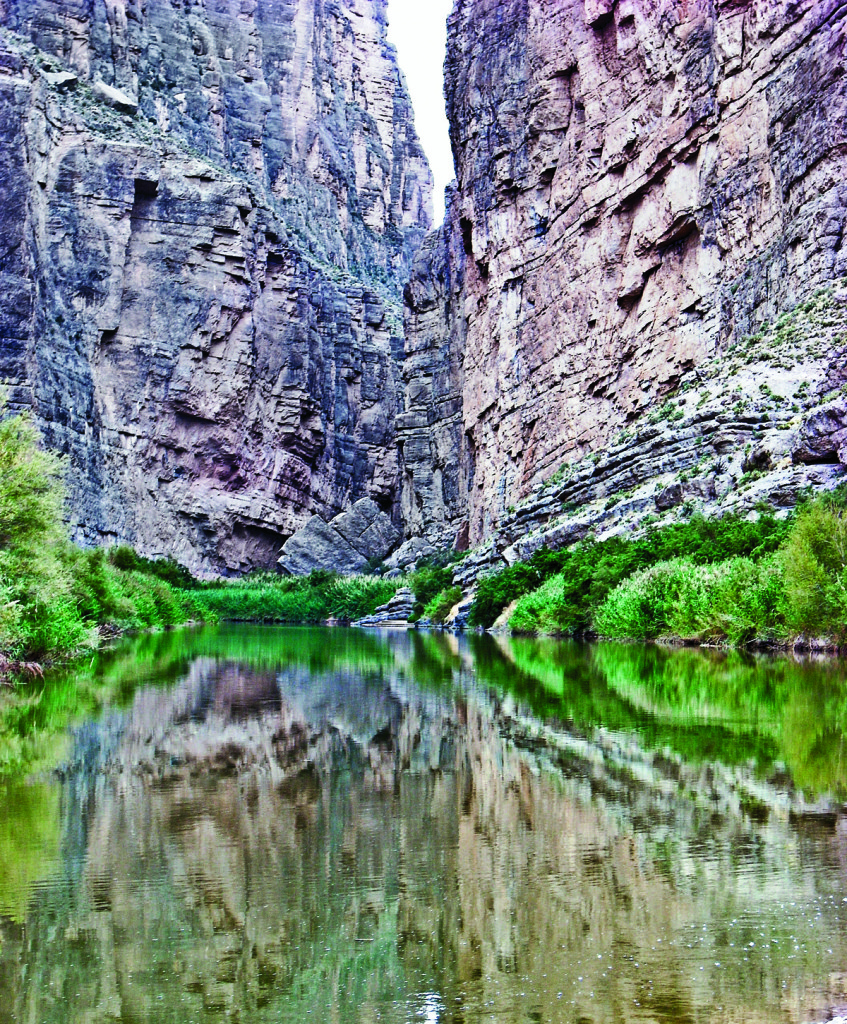

Early risers can hump it deep into Big Bend for a visual extravaganza in Santa Elena Canyon as the sun breaks over the mountains and spray paints the canyon walls with colors that artists eat their hearts out to replicate. Beware of rains anywhere within a hundred miles of the park. Flash floods racing down any canyon, arroyo, wadi or wash can be disastrous. When afternoon rains threated, we took refuge in the high Chisos Basin and watched the thunderstorms drag rainbows across the surrounding mountaintops. The Lodge, located in the basin at over 5,000 feet, offers full hotel services with a restaurant as well as a trailhead for hikers fanning out on the many trails into the mountains. The campground nearby is popular for its climate and proximity to all the various sites in the park.

When the sun began its run for the other side of the world, we carefully made our way down the twisting road out of the Chisos Mountains, pausing for the occasional deer ogling us from the center of the road. During the ride westward to Study Butte, Big Bend continued to cast its spell of beauty and harshness, conflict and harmony.

In Study Butte-Terlinqua (of chili cook-off fame), we checked in at Big Bend Motor Inn and parked ourselves on the veranda, refreshments in hand, to observe another flaming sunset. When it was done, we headed off to the Kiva for underground barbecue and river-rat music.

The last truly technical, gorgeous and sometimes hairy route is FM 170, known as the Camino Real. It flows 70 miles from Study Butte westward to Presidio, past the new resort of Lajitas and winds alongside the Rio Grande, which marks the southern boundary of the rugged Big Bend State Park (as distinguished from the National Park). The road surface, except for the low water crossings, is generally good and the views are stupendous, but the combination of severe elevation changes, some decreasing radius and off-camber blind curves, with the occasional javelina herd lounging across the road, can cause problems for the unwary, unskilled or just plain foolish.

From Presidio, U.S. 67 led us northward, through the Chinati Mountains to Marfa (of the mysterious “lights” fame). From there, State Route 17 soon delivered us to historic Fort Davis. Nestled in the southeastern corner of the Davis Mountains, the fort was established in 1854 and is one of the best remaining examples of a frontier military post in the U.S.

There are a number of good places to stay in Fort Davis, but I recommend the Limpia Hotel. Built in 1912, it has been restored with old-world charm and offers many amenities, like a pool and a good restaurant. Advance reservations are advisable at the Limpia, as well as at all the overnight lodging places mentioned, because winter and early spring is peak season. The scenic loop on State Routes 118 and 166, running through the Davis Mountains past the famous McDonald Observatory, is a great afternoon excursion.

After dinner, we made our way back up Route 118, a writhing, 16-mile climb to the McDonald Observatory, to enjoy the highlight and virtual culmination of our trip—the observatory’s Twilight Program and after-dark Star Party. Again, reservations in advance are advised. This facility is owned by the University of Texas at Austin and is one of the foremost astronomical research facilities in the world. It is located on one of the “darkest” sites in the U.S. The high altitude and stable air above the Davis Mountains ensure the view of the sky is clear and sharp, allowing stars, galaxies and planets to shine through. Bring warm clothing even if it is warm in Fort Davis, and try to avoid a full moon as its light interferes with the view. Probing into deep space through huge telescopes, we observed the Andromeda Galaxy, which is 2.5 million light-years away from the Milky Way and twice its size with over a trillion stars.

The ride back down the mountain to Fort Davis at 11 p.m is almost ethereal but requires focus. Deer and javelina often loiter in numbers on and alongside this road, especially at night. We kept the speeds down and the eyes up.

If there is time, I recommend taking a day at the observatory for real-time solar viewing and a guided tour of the entire facility, which continues to grow with new telescopes, instruments and researchers who push the frontier of astronomical research. Spur 78, the road to the top of Mount Locke, is the highest public road in Texas, with an elevation of 6,791 feet. On top are the Otto Struve (82-inch) and the Harlan J. Smith (107-inch) mirrored telescopes. Over on Mt. Fowlkes is the Hobby-Eberly Telescope, a revolutionary optical device designed for spectroscopy, which is responsible for the lion’s share of current astronomical knowledge.

We are not ready to leave this country, but at some point we must pick a route back to Dallas/Fort Worth. The quickest one leads north along State Route 17, intersecting Interstate 20 north of Balmorhea. Then we slabbed it the remaining 450 miles, arriving in Dallas before the 6 p.m. news with great memories of another wild ride in Big Bend.

(This article Wild Texas: A Winter Ride to Big Bend was published in the May 2013 issue of Rider magazine.)

Big Bend is my favorite place to ride in Texas. I hope to get back there next spring. Great post and pictures.

Thanks for the memories… Ride safe and I hope we see you down the road somewhere…