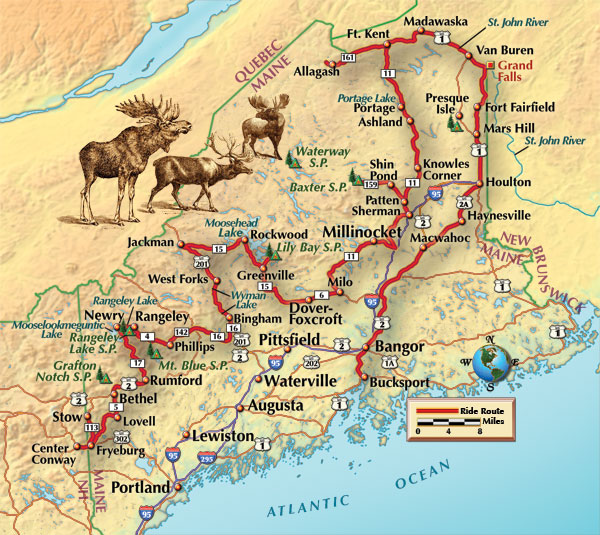

The premise took hold in my mind after recently moving from San Diego to New York. Why not complete the journey from the extreme Southwest corner of the United States to the most Northeastern quadrant? On my map that looked to be Madawaska, Maine. All right, Rider hadn’t published a tour story about Maine in quite some time, so off I rode in search of finality…and moose.

Just inside Maine I rolled northward on State Route 5 to Bethel, a place on someone’s list of the top 10 outdoors towns in which to live. Downtown is a National Historical District that includes Gould Academy, one of Maine’s oldest prep schools. It’s also the locale of an annual Western Maine European Motorcycle Meet.

My first encounter with moose occurred near Rumford, sort of. A roadside stand offered moose horns for sale. The seller told me artisans generally buy them to design furniture or to carve them into intricate crafts. He judges the price by weight, looks and size, charging $8-$10 a pound. Even the smallest horn cost $70. Yikes! My guess is it would make an interesting adornment for a cruiser or chopper.

I passed through Rumford, where Androscoggin Falls provides hydropower for the sprawling paper mill. I left the belching smokestacks behind by following State Route 17 north alongside Swift River. Although bumpy and frost-heaved, the road rises through woods and past ponds until it crests the Appalachian Trail. My senses were smacked aware by the sight of forested mountains rimming a series of interconnected lakes and rivers swallowing the distance.

Then I was on the Height of Land Overlook, gazing at the blue sheen of Mooselookmeguntic Lake and a greenish tint of the Alleghenies extending into New Hampshire. Maine contains 6,000 lakes and 32,000 miles of rivers, and here lies a pretty fine sample. A bit farther along I passed another overlook offering up a panorama of Rangeley Lake and a succession of peaks above 4,000 feet. Soon I’d wrapped around Rangeley Lake itself and crossed the Appalachian Trail once again, picking up State Route 142 to glide alongside another mountain background. Unadulterated riding pleasure continued unabated along State Route 16 through coniferous forest, open meadowland and quaint villages hugging the bends of various rivers.

Sensory overload began anew on U.S. 201 north of Bingham. I caught up with a group of motorcyclists, and we swayed with the curves lashing Wyman Lake for miles as a film reel of mountain frieze rolled by. Soon we rambled along the Kennebec River across the Appalachian Trail yet again to West Forks, where rafters and kayakers charged the riffles and rapids.

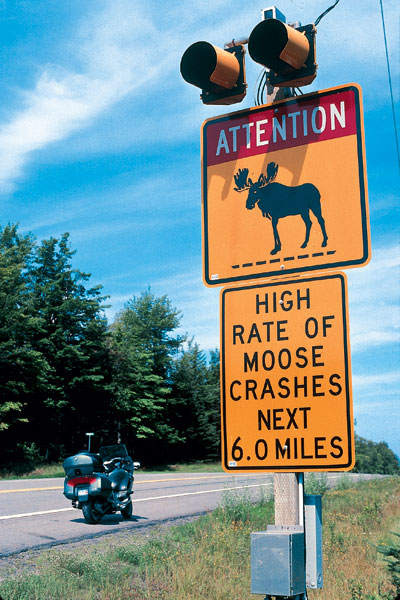

Out of West Forks Beemer and I plunged into pure wilderness. Signs appeared showing a moose in silhouette and flashing alternating amber lights, declaring Emergency—Dangerous Moose Crossing Next 35 miles. Periodically I would notice swerving skid marks on the road in areas with no crossroads or other hazards. It slowly dawned on me that drivers were braking hard to avoid moose; it’s not for nothing the speed limit is held at 55 mph.

We rolled through the Kennebec Watershed and arrived in Jackman, a lonesome outpost virtually on the edge of the wilderness. Simple saltbox structures with peaked roofs reflect an Acadian population, Americans of French descent who immigrated from Canada. Most information signs in Northern Maine are written in both English and French. My biker compatriots are Quebec bound, so we parted after a fill-up of 87 octane; no high-test in the boondocks.

I headed east through the canopied landscape over State Routes 15/6. Nearly 90 percent of Maine is forested, and I often felt claustrophobic tunneling through a viewless slot. After 30 miles or so of enduring the Beemer’s infernal pinging at every twist of the throttle, the sight of more lakes, rivers and mountains alleviated my ennui. Near Rockwood the Moose River empties into Moosehead Lake beneath the prominence of Mount Kineo, a Maine landmark because of its Gibraltar-like prominence.

Out of Greenville on the south shore of Moosehead Lake, I took an unnumbered spur north to Lily Bay State Park. I learned that this is an old tote road. Long before there were state highways in Maine, logging trucks stamped out tote roads. Throughout northern Maine are spurs that seemingly go nowhere, but in actuality feed to an extensive private road network used by lumbermen to clear timber. These roads were also the only way that supplies could be transported to the remote settlements in Maine’s frontier. Steamboats also plied the lakes, and in Greenville you can still experience a float on the Katahdin, now a museum. Seaplanes are a modern transportation way of life up here, and I spot them clustered about, some available for sightseeing excursions.

After a night camped along the wooded shoreline of ultra-clear Moosehead Lake, I continued south on State Routes 15/6. Here again were moose warning signs. I had inquired about moose the previous afternoon in a Greenville café, and was told by the waitress that if I wanted to see moose, take this road to the DOT maintenance yard at dusk. “The most dangerous time!” piped up a diner. “You’ll more ’n likely hit one,” chimed another; “If a crazed logger doesn’t hit you first,” he added. I made a cowardly retreat to my campsite. By the light of day the signs didn’t mince words: High Rate of Moose Crashes Next Six Miles.

I hooked up again with scenic Route 16 heading east past the distinctive spire of the Congregational Church in Dover-Foxcroft. American flags flapped from virtually every telephone pole entering and exiting Milo, another village embracing a picturesque river bend. State Route 11 became another single-barrel shot through thick woodland to Millinocket, where more flags jutted from just about every stanchion. I discovered that regions throughout this patriotic state hoist their flags on Memorial Day and keep them flying through July 4 and beyond.

I obtained 93 octane in Millinocket and the Beemer responded with a satisfying burp as we continued up Route 11, swaying alongside this river route past Grindstone Falls and its unique rapids burbling over striated rock. Out of Sherman the road elevates to a turnout revealing a 360-degree sweep of Maine in contrast. Fields of potato blossoms fill the hillsides. Eastward looms the Aroostook Plateau. Westward across a valley of forestland rise the successive peaks of Baxter State Park, including prominent Mount Katahdin at 5,267 feet. On this mountaintop begins the Appalachian Trail. The road undulates northward from here to Patten.

Patten is home to the Lumbermen’s Museum, appropriate since State Route 159 from here to Shin Pond joins another tote road, one in service for more than 175 years. This must still be the lifeline of Maine’s modern lumber industry, because I encountered truckload after truckload of rolling thunder blasting past as I headed toward Shin Pond. I paused by two seaplanes resting in an idyllic cove like contented waterfowl. I stopped to fill my canteen with spring water gushing forth out of a standpipe protruding from the hillside.

The road ahead rose, dipped and curved through deep woods until I spotted two Baxter Park peaks poised above a sharp bend. I paused to photograph—a fortunate act—because as I dismounted a behemoth filled the bend with its bulk, issuing forth a staccato growling as it careened through the apex at a speed I would fear to go.

Late afternoon shadows rippled across the road in the logging truck’s wake. Do I continue up this delightful, twisty tarmac for a chance encounter with a 100,000-pound brute, or backtrack for a possible collision with a 1,500-pound moose? Lesser of the two evils, I decided, so it was return to Patten, where I calmed nerves with a lumberman’s meal of eggs, corned beef hash and a side of beans at Debbie’s Deli.

Route 11 due north of Patten enters Aroostook County, the largest one east of the Mississippi River. The road sweetly roller coasters and gently curves through the North Woods, occasionally zipping apart the pine and spruce as it unravels into the pastoral distance. We entered the Fish River Valley past Portage, the landscape filling now with grasslands and wildflower meadows. Lupine splashed various shades of lavender brushstrokes along the roadside.

My northward trek halted at Fort Kent along the St. John River. I felt compelled to seek road’s end toward Allagash. Some 30 miles later I encountered locked gates and the beginning of gravel roads launching into the Allagash Wilderness. With no intent of taking the 850-pound BMW into no-man’s land, I backtracked to locate camping.

I happened upon Two Rivers Lunch Diner, a rustic enclave full of game heads mounted to every available wall space, and large maple tables supported by tree trunk legs. “Dinner ’til sixish,” I was told by the proprietress. It was close enough, so I took her up on the offer. I was directed to McBreairty Lodge for camping. I pulled up to a well-kept clapboard house, and there on the porch contentedly swinging away was an elderly lady who introduced herself as 89-year-old Evelyn. Her daughter helps to run the adjacent McBreairty Lodge, she informed me.

“I was born right up the road,” the still spry Miss Evelyn intoned. “My husband ran the ferry across the Allagash for 36 years until the bridge was put in. He built this house for us in ’47. You want to camp down along the river you’ll need my permission,” she stated firmly. After sweet-talking Miss Evelyn, I got her OK.

The rising sun lured me back to Fort Kent where I picked up the start of U.S. 1, a highway that follows the Eastern seaboard all the way to Key West. Now there’s a tour idea! But I would be content to make Madawaska, not knowing what to expect. Wouldn’t you know it, a billboard appeared on the outskirts proclaiming Madawaska the most “North Eastern Town of the United States,” and officially acknowledging it as “one of the four corners.” In the midst of town next to a McDonald’s I discovered a granite monument topped by a carved outline of the United States, further emphasizing the notion. Across the street they were even building a memorial recognizing the Perimeter Run phenomenon.

Beemer and I glided along a glossy slope angling down to the St. John River dividing the United States and Canada. The land abruptly rose again on the Quebec side, displaying a forested mountain backdrop. We breezed past wide-open fields and farmland. I stopped to visit an Acadian Village outside of Van Buren. This got me to thinking that I couldn’t come this close to Canada and not cross over, so I jumped the river to check out Great Falls, so named because located here is the largest waterfall east of Niagara. The St. John River cut a gorge through Canadian Shield rock, and during spring freshet the falls produce a foaming, thunderous volume nearly equaling Niagara.

Time to drop south following U.S. 1 past mixed groves of hardwood and pine. I skirted the city of Presque Isle by heading down U.S. 1A, passing a wind farm and ski area on Mars Hill. Route 2A out of Houlton plunged us back into forest until meeting up with U.S. 2 flowing lazily alongside the Penobscot River. Timber used to choke this wide river during the great log drives 100 years ago, destroying bridges and docks in the process. I passed through Bangor, hometown of scaremeister author Stephen King. There are even moose warning signs for the six-mile stretch of Interstsate 95 through downtown Bangor, for gosh sakes.

I stumbled across a festival in Bucksport celebrating the grand opening of the Penobscot Narrows Bridge, an impressive cable-stay design supported by two 445-foot obelisk towers. From the picturesque Bucksport waterfront this architectural artwork beautifully framed the 75-year-old suspension bridge it replaces. Being held concurrently at the waterfront was a Bikefest sponsored by the United Bikers of Maine. This group publishes a slick Maine motorcycling touring guide endorsed by Governor John Baldacci, himself a rider (contact www.RideMaine.net).

I learned one of the bridge towers held an observation deck, the only bridge with an observatory on the American continent; indeed, only one of three such bridges in the entire world. Not one to miss an opportunity, I grabbed the last ticket of the day and headed up the tower. Below the 420-foot level of the obelisk lay a New England sampler of bay waters caressing a charming waterfront town defined by chapel steeples puncturing a wooded countryside, further extending to a mountain backdrop. One plaque said you can see Mount Katahdin 100 miles away on a clear day. I couldn’t, but it only reminded me of what else I didn’t see.

I saw moose horns; I saw moose heads; I saw moose figures and moose ornaments; I saw moose signs; I saw Moose River, Moosehead Lake, Moose Lodge, even Moose Crossing; I also saw a moosehead light switch and a fanciful flying moose. But I saw no moose. An uncanny occurrence made up for it, though.

I squinted out the observatory window, looking into the distance and recalling when I was on the Shin Pond tote road setting up for pictures. Throwing all caution to the wind, I’d parked the bike dead center on the road pointing toward me, and set up a tripod roadside with camera attached facing the BMW and that scenic bend in the road. If all worked well I would run to the bike while the timer counted down and get my shot. My senses were alert for any faint tremble, any auditory signal of an approaching growling beast, when I heard something else, a thrashing in the dense woods, then a crashing, followed by a snort; at least, I think it was a snort.

I may not have seen a moose, but dad-gum-it, no one can tell me I didn’t hear a moose!

Thanks for the article Alan. I’m heading up this way in the spring.