The eerie thing about the Bonneville Salt Flats is exactly what makes them so good for high-speed runs—-their flatness. I’m sitting on my 2006 Triumph Bonneville T100 in the prestaging area, very glad that I’m the second bike in line, not the first, because I’m not sure where we’re supposed to go. The staff fellow waves five of us off and we head across the salt. No signposts, just the occasional blue markings on the white salt. After a mile we see three small canopies set up, with RWB written on the salt; that is our staging area.

None of us are going for records. We are in the Run Watcha Brung class, where anybody can show up on any bike, and as long as the motorcycle and the rider’s kit passes safety scrutiny, off you go. Nuts and bolts like drain plugs and wheel axles have to be safety wired. A Snell 2010-approved helmet is required, and leather for all vestments—gloves, boots and suit, be it one-piece or a two-piece that zips together. Apparently man-made fibers do not do very well when sliding along the salt at 100 mph.

Everyone has heard of Bonneville as the place to go fast. The salt flats cover about 30,000 acres at the western edge of Utah’s Great Salt Lake Desert, which stretches for roughly 4,000 square miles from Salt Lake City to the Nevada border. Big. In 1914 a fellow in a Blitzen-Benz automobile claimed to have gone 141 mph on the flats, but regular speed trials did not begin until 1925. Then in 1956 a Triumph-powered streamliner went 214.47 mph, and the Triumph Company decided to name a 1959 motorcycle model after the place. So what better bike to run at Bonneville today than the latest eponymous Triumph?

The flats can be rented from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management for events like the BUB Motorcycle Speed Trials, which Denis Manning started in 2004. He owns the Big Ugly Bastard company that makes motorcycle exhaust systems. The deal here is that you can run for fun, or run for a record, and Denis pays for both AMA and FIM (the international equivalent) officials to be on hand with their timing equipment. For $150 I could go and do two passes in the RWB class; if I got hooked on the salt, I could pay for more.

Record-seekers paid $650 and could run until they got a record, or the engine blew up. It was $20 a day for spectators.

Chris Sidah, the magazine’s Tech Q&A contributor, and I loaded my 2006 Triumph Bonneville T100 into the back of his pickup, with our two Suzuki DR650s on a trailer for play bikes. Eight hundred miles later we pulled into the Wendover Motel 6 on a Friday evening. At $35 a night this place is home to a lot of go-fast enthusiasts who would rather put their money into camshafts and tires than fancy rooms.

Next to us a fellow had a fully faired Yamaha SR500 tucked into the back of a van, and he introduced us to the rest of the Sodium Distortion gang—a play on salt addiction. This loose-knit group has been coming out to the flats for the past nine years, and they were hauling some mildly bizarre machinery, including two very long unfaired bikes designed with minimal frontage, the engines being behind the crouching rider, the wheelbases probably 180 inches or so. We were advised to be out at the access road by 6 a.m. Four miles east of the motel a sign on Interstate 80 points to the Bonneville Salt Flats, with a paved road leading out to the salt. At the end of the asphalt is a check-in point, making sure that everybody who goes on the flats has signed a waiver accepting the risks involved.

Check-in would not open until eight o’clock, but the idea was to be near the head of the line when the action began. Chris and I got up in the dark and were there shortly after six…with two dozen trucks and vans already in front of us. The socialization is great, meeting and greeting, talking with old friends and new acquaintances, this kind of fraternity being the heart and soul of the week. No bushes, trees or hiding places, should you happen to be called by nature, so BUB is kind enough to place some honey pots along the road.

Checked in, waivers signed, wrist bands on, at nine o’clock the first van with bike in back heads east onto the flats, with orange cones every half mile or so the only indication of where to go. After some five miles cars, trucks and a big trailer appear on the horizon—the pits. There are no

formal sites, but eventually three rows of vehicles and canopies and motorcycles lined up, with more than a hundred feet between the rows. The easternmost row faced the return road, marked by a dotted blue line. Parallel to that and a quarter mile farther east was the five-mile short course, and beyond that the 11-mile long course.

Saturday was merely paperwork, inspection and getting organized; no runs. We set up our canopy, off-loaded the Bonneville, and I walked down to register. Then I took the bike and my gear down for scrutinizing. The Bonnie, thanks to Chris’s meticulous work, passed without a problem, as did my gear: a Hein Gericke two-piece suit, Roadgear gloves and boots and a Bell Star helmet.

In the afternoon we left the Triumph and canopy at the pits and went riding on the DRs in the mountains west of the flats. Good fun, but it got a bit windy, so we headed back to take down our canopy, leaving just the frame. When the wind blows out there, it can create mischief. On race days, all action is stopped if the wind exceeds 10 mph, and the streamliners can’t run if it is over 3.5 mph. Tricky little devils, those streamers, and expensive to crash.

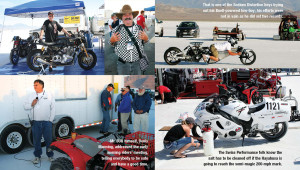

Scotty Murnan rode his 1977 Harley Shovelhead out from Indiana to try to get to 100 mph, ape-hangers and all; he did not make it. Second from left: Victory over Clement by Triumph Bonneville riding Brook Rosberg was celebrated with her daughter and a pair of shaved-ice cones. Second from right: The author is getting ready to go to the Run Watcha Brung line and have a second go at reaching 106 mph—sorry, only 105.957.

I walked through the pits, where more than a hundred crews had set up. Somebody had lashed two Honda 175 twins into a sidecar outfit. A Yankee 500 looked set to go fast. A Victory Vision had a number plate. English motojournalist Alan Cathcart would be riding the new Norton 961. There was Max Lambky’s twin-engined Vincent streamliner, with a half dozen famed Vincenteers sitting in the shade discussing the old days. One of them was Marty Dickerson, who first ran the salt in 1950 and set a record last year on a Vincent at age 83; he is definitely addicted to the salt. A stock 2005 Triumph Bonneville is on our row, ridden by Brook Rosberg, an attractive lady from Chicago. That will be my competition, and she is a good deal more aerodynamic than me.

Sunday was the big one…for me and the two-run RWB riders. The record-busters would be out there for five days, tuning, retuning, fiddling, trying to eke out one or two more mph. I have no idea how many AMA and FIM records there are, from vintage flatheads to the latest top-fuel contender, but the list runs into the hundreds. And when you make a record run, you know that it is there waiting for the next person to break it.

The riders meeting was at 7 a.m., and I was there early. Denis gave us a briefing, saying that since he holds the world record, at 367.382 mph, his Lucky 7 is not going to be running today. None of his serious competitors were on hand for this event, but they were plotting somewhere. A small second meeting is held for all the new guys, to make sure they would know where to go and not mistakenly cross a track with someone approaching at 200 mph. Pre-staging started at nine.

After the wave-off we rolled along to our staging area. To speed things up, so to speak, RWB would be running miles 1-4 on the short course, rather than 0-5: first mile to accelerate, second to hug the gas tank and get measured, third to slow down and angle left to the return lane. Once a new rider understands the basics of the layout, it all seems simple, but had I been by myself I might still be out there, circling the salt.

My turn; wire up the kickstand. Go forward 50 yards to where the flagman is standing 20 feet from the track. His radio tells him the track is clear. Flagger tells me to check that my visor is down, chin-strap tight, waves the green flag and I ride forward 10 yards to make a 90-degree turn onto the track, worn smooth and flat. I’m a bit over-enthusiastic, or nervous, and as I twist the throttle the rear tire spins. Back off, get straight, and now I have a mile to accelerate to the max, redline in first, second, third, fourth—the engine seems to be peaked at 6,800 rpm. Fifth gear. The two-mile marker flashes by as the speedometer reads 105 mph. I hold the throttle and hunker down. Three-mile marker goes by. I back off, and half a mile later turn onto a well-beaten escape road, ride over to the return lane and back to the pits.

Chris greeted me with a slip that read 105.705, thanks to the instancy of the computer world. Then I was back in line, back on the track, trying to crawl under the paint—and managed to eke out another quarter-mph, to 105.957. Brook pulls 106.9—I have lost.

Maybe I should lose a lot of weight and go back next year…an indication that one is suffering from salt addiction.

Postscript: Cathcart set a record for Production Pushrod on the Norton at 129.191, and the Sodium Distortion gang got two records. Three weeks later, at another speed meet at Bonneville, the Ack Attack beat the BUB Lucky 7 record by going 376.156 mph.

(This article Bonneville To Bonneville: Running the Time Traps at the 2010 BUB Motorcycle Speed Trials was published in the January 2011 issue of Rider magazine.)