story and photography by Bob Jacobs

[Virginia Motorcycle Rides: A Civil War Ride was originally published as a Favorite Ride in the October 2009 issue of Rider magazine]

Medications always come with risks as well as benefits. The Doc says, “Take one of these every day. Let me know if you experience any side effects.” The main side effect of living, of course, is dying. Life causes death. We get to weigh that against the benefits of having deep, meaningful relationships, self-awareness, knowing love, seeing stars in the midnight heavens—not to mention cold beer and hot dogs.

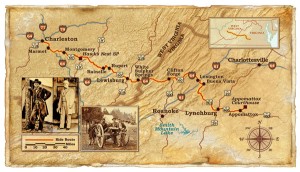

All of this occurs to me as I heel my Harley Ultra over again, scraping the jiffy stand in a tightening, left twisty southbound on West Virginia’s highway 60 running from Charleston to Lewisburg. Alone in the mountain morning, I pull off to snap a picture down into the shallow river valley along which this byway snakes its way toward biker bliss, green beyond all belief, smoky blue in the distance. The surround-sound audio track is a whisper of wind in the oak and maple leaves arching over me, birdsong mingling with the tinkle of hot pipes cooling in the shade. Three days away from home in the flat, fertile farmland of Illinois, I’m having side effects.

The wife, Max by name, says one day, “The family reunion is at Nags Head, North Carolina, this July. We’re going.” I say, “Great, sweetheart, let’s ride.” She says, “Nice try, but I only get two weeks off work, and it’s the folks’ 50th anniversary. I’m doing all the arranging, so I’m flying down. You take the bike if you want, but show up before it’s over, dude, or…else.” She has a way of emphasizing “else” that makes me shiver.

Side effect: I’m on the road, soloing through this green paradise of a state in mountains that by California and Colorado standards would be called “hills,” but that here—where the Civil War is not quite over and done with—are mountains, whether my friends out west like it or not. I’m standing beside the bike just past Hawk’s Nest State Park, taking another picture of it against the grandly twisting road, when a guy in a pickup truck that I couldn’t identify through the rust and added-on ricks and racks in the bed, pulls to a stop. The guy wants to know if “everthin’s OK.” I don’t know about everything, but I tell him that the bike and I are just fine. “Ever rid the mountins before?” he asks, spotting my Illinois plates. “Not these ones,” I reply. “Well, these are good ’uns,” he grins. “Some nice switchbacks come up in a couple of miles. Take ’er easy, and ride safe.” So saying, he pulled away, leaving a blue exhaust trail.

At lunch in Lewisburg, I look at my map, and see that if I continue into Virginia from here, there’s a place that brings a niggle to my soul. Appomattox.

There are holy places in this country. Last year I rode to Gettysburg, where Americans suffered almost as many casualties in three days as we did in 10 years of Vietnam, and turned the tide that would wash up two years later at a home in Appomattox Court House, Virginia. That event in Gettysburg was a side effect of one company of General Lee’s soldiers making a detour into a town on their way around it to see about buying some shoes. They were spotted by a Union Army lieutenant from Illinois, who started the shooting that would turn the fields red with blood and drive the Confederates back south forever.

I ride Interstate 64 across the Allegheny Mountains and the Shenandoah Mountains, all looking the same to me, to Buena Vista, Virginia, then head south on the rollercoaster that is Route 501 across George Washington National Forest to Lynchburg. Route 460 from there is a rolling four-lane that puts me off on the road to Appomattox Court House National Historic Park.

It rained most of the way down, but here the sky was a startling blue, studded with puffballs like cotton, once the staple of the South that figured as a major cause of our not-so Civil War. On April 2, 1865, that war was drawing to an inevitable conclusion as General Grant—having taken Richmond and then Petersburg—was forcing General Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia to begin retreating west toward Lynchburg. The retreat was a costly one, with skirmishes taking hundreds more lives before Grant’s forces pushed the Confederates into a bottleneck valley that ended at Appomattox Station. On April 8th at about four in the afternoon, Brevet Major General George Armstrong Custer led a massive charge that defeated the last Southern brigade guarding Lee’s flank two miles west of Appomattox Court House. The next morning, Grant got a letter from Lee asking for a meeting.

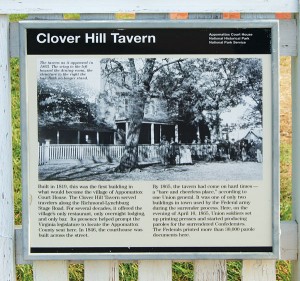

I parked the big Harley practically on the same spot where the Union forces would have been bivouacked, and walked up a slight grade to the home of Wilmer McLean. This house, where Lee and his adjutants waited on that April morning for the arrival of Ulysses S. Grant and his staff, stands today virtually the same as it was then. I went up the same front steps trod by two gallant generals, entered the hallway of the house and turned left into the parlor. There stands the marble-top parlor table where Lee sat, and a few feet away, the oval spool spindle table made of pine used by Grant. The unremarkable smatter of buildings marking the town—a tavern, a farmhouse, the McLean slave quarters—look just as they did when the two warriors exchanged letters of agreement to the surrender…and the war was over.

As afternoon brought forth the golden apple of the sun, I rode out past the cemetery at Appomattox holding the graves of 18 Confederate soldiers, maintained lovingly by the Daughters of the Confederacy. One of them told me that “the South never really surrendered here. It just quit fighting.”

I made the family reunion in Nags Head on time. It’s a family of terrifically diverse opinions, lifestyles and ethnicities, just like the rest of America. And the side effect of my bike trip to commune with my personal God of the highway for a few days was a revelation. People are wrong to think of Appomattox as a surrender. Grant and Lee, two noble Americans, spent an hour or so in that parlor talking about old times, shared memories and regrets about the horrible killing. Unlike the common belief, Grant did not ask Lee for his ceremonial sword. Grant was covered in dirt from his long ride in from Farmville. Taking a sword was far less important to him than taking a bath. Appomattox was, in fact, a reconciliation of a broken family.

The side effect of war is, after all, inevitably peace. A few days after Grant and Lee went their separate ways, President Abraham Lincoln in Washington told the assembled Union Army Band, “We have won a beautiful song. Will the band please play ‘Dixie’?”

The 618,000 who died in that damned war were, each and every one, an American. And Appomattox Court House, Virginia, it turns out, is the place where their sacrifice is enshrined, not as a memorial to winners and losers, but as our national family reunion.

Hi Bob, Really enjoyed your article. I live in Frederick Md. and enjoy riding the battlefield at Gettysburg among other civil war locations on my motorcycle. I figure you know this but the civil war started in Wilmer McLean’s front yard (1st battle of Manassas) as his house was the HQ for Beauregard and ended in his front parlor at Appomattox. Kinda neat. Take care and ride safe.

Andrew Husser

There were foreign fighters who participated in the US Civil War – more for the Union than the Confederacy.