Riding and Life Lessons on a Big Scenic Loop

When Don Scott, my neighbor and riding buddy, mentioned he wanted to go on a long ride—nothing but blue highways, maybe across Canada, a loop through the Rockies—I reached for the road atlas. Tucked away on the western edge of Montana was a town called Wisdom. It seemed a noble and appropriate destination.

I sketched out a route. Nothing complicated. I don’t believe in GPS, MapQuest or anything that requires putting on bifocals at speed. We would leave Evanston the day after Labor Day, go to the Mississippi River and turn right. At Duluth, hang a left. A day later, turn right. Cross into Canada to Winnipeg. Turn left. Follow the Yellow Head Trail until we ran into the Canadian Rockies, take another left. Eventually, we’d come to the town of Wisdom.

Day One: Crossing Wisconsin we pass franchises offering excitement to flatlanders. Extreme fireworks. Victory fireworks. Old Glory fireworks. Shockwave, the adult video store. Plowrider, wave surfing at an indoor water park. Such and such Harley-Davidson. This is familiar territory, the stuff of weekend escapes. We pass through towns so small everyone makes the football team. Crammed between the river and the rock bluffs, every town has a roadhouse, saloon or café, an auto body shop. Harleys nurse curbsides in litters. A sign hanging on a wagon parked roadside states simply: Pleasant Surroundings.

We look for rhythms and omens. Nearing the Mississippi we are transfixed by a sense of vast wingspans, whirling hunger—three blue herons circle above the hills. On a smaller scale, hawks work the updrafts over the bluffs along the river. We share the sense of flight.

We take a rest stop by the river, watch a local drive his pickup to water’s edge and slightly beyond. He tosses sticks into the river for his dog to retrieve.

If we had a timetable, an ETA to reach a specific town by nightfall, we abandon it immediately for a pace that allows good food, conversation, reflection. Mileage is not our master. When night falls we stop in Frederic, a small town 72 miles shy of Duluth. We walk to dinner.

Over dinner we discuss the learning curve. This is Don’s first long trip. He has discovered that his bike can run all day, mile after mile, and be as fresh at the end of the day as the beginning. (Something not to be said for the riders.) And it can do that for days on end. Anything is possible.

Lesson: Stop one town short of the obvious destination, i.e., don’t end a day in a major town. Everyone will be headed there (it’s the nature of MapQuest).

Day Two: We pass through towns where the churches outnumber the fireworks stores, but only just. Road signs warn of snowmobile and ATV crossings, as though motorheads were just another form of wildlife. What looks like a largemouth bass impaled on a stake turns out to be a mailbox. Welcome to the North Woods.

We cross Minnesota on Route 2, through a forest of poplar and pine. In the ’30s robber barons cut a 60-mile swath through the hardwood forest. The quick growing species reclaimed the land, creating an unintentional monocrop. The towns are relics. Wide streets and boardwalks indicate former resort destinations, famous for vice, fishing and other seasonal male pursuits.

In the afternoon, turning north, we pass farms so vast, I think, if the fields were fairways, each hole would be a par 200. We pass farms with three, five and seven silos. We contemplate the wealth generated by the land.

We cross into Canada and decide to stay in Morris rather than push on to Winnipeg. Burke’s, the family restaurant across from the Motel 8, closes at 9 but they welcome us anyway, letting us cook sirloin and T-bone on an indoor barbecue pit.

Lesson: There’s no such thing as too many stops. Motorcycling is a sedentary sport. Stretch your legs. Even people who have desk jobs don’t sit at their desks all day.

Day Three: The day begins with a wheat field the color of gold, a color you only find in impressionist paintings and songs by Sting. The day will continue the palette. It will end in a wheat field. Twelve hours straight, every hue of gold, tan, green and gray. Hay in rolls stacked five high. Fields of stubble. A hawk sitting on one hay roll surveying the field before him like a diner consulting a menu.

The colors change throughout the day, depending on the angle of the sun, or the time that has passed since the harvest. One field has the mad swirls of van Gogh tempered by the cold efficiency of a Zamboni driver, the color reflecting the direction of the blade. Oddly, a day of wheat is far from boring. Now I know why Monet painted the same haystacks 28 times.

Toward the end of the day the terrain shifts from absolute flatness to small hills and mounds. Water trapped in roadside depressions captures the golden stubble—each pond looks like it has the eyelid of a snake, retracting as the angle changes.

We ride toward clouds. It is impossible to judge due west, but the obscured sun still illuminates the edges of higher clouds, visible through patches of blue. What appear to be mountains on the horizon are potash mines. For the first time in five decades I wish I’d paid more attention to those grade school maps with tiny symbols for crops, minerals, livestock. And other resources. Nothing prepares you for the size, the abundance. What is potash?

I tend toward silence and observation, fly-on-the-wall journalism. Don is more garrulous. He believes in the European notion that “Time is relationship.” He makes a human contact at every pit stop, meal and roadside encounter. Over breakfast he asks the waitress what she knows about potash. I watch her face as she recounts a tour of a mine, descending on an elevator for 20 minutes. Her guides opened a panel in the side of the cage and she watched the earth rush past. She watched men dig out rooms of potash, rooms the size of warehouses. When she returned to the surface she could taste something like salt on her lips. She thought it was used in fertilizer, but the fact was not as transfixing as the look on her face as she relived the descent.

I call Don the conversational equivalent of a Seeing Eye dog.

Lesson: Scenery has a human component.

Day Four: As we head across Canada, I recall snatches of a song by Ian & Sylvia, two folksingers from the ’60s, something about short grass, cowboys and the land: “The sun burns the snow high on the mountain, it runs and it roils to the sea/Silt and soil, down it pours/down to the river the gold river flows/to the sea.”

We are riding the song in reverse. The Plains are slowly rising, a process we notice only when the land falls away. We stop on the edge of a valley cut by the Saskatchewan River, and look down into beauty. For hours we ride the ridge, skirting a plateau to the north, a declining slope to the south. Ghost Riders in the Sky replaces the song about landscape.

Today, we ride the sky. You can see weather cells form 50 miles away, watch thunderheads climb 50,000 feet in a half hour, clouds that look like the Three Mile Island cooling towers turned upside down. Clouds do what clouds have never done before, assume shapes that make no sense, that threaten, then release rain.

In the space of minutes we are pelted by hail, rain and a flurry of snow. Back home, we’d wait out the weather under an overpass. Canada, it seems, does not waste money on such frills. Here there are intersections. Roads cross. Deal with it.

At a gas station café the owner invites us to wait out the downpour with pie and hot tea. Another customer says he’s willing to buy our bikes, real cheap.

We push on. The rain stops, but the clouds gain a dark mass that obliterates the sky, save a narrow band of blue to our west. As we reach Saskatoon, a setting sun fills that gap with blinding, blood-red light, which seems to shatter and reform, becoming the neon of the city.

That night, we compare notes. Don is bothered by a sense of disorientation, that he has become untethered from time. I tell him it’s normal on tours. I call it combat time—much of your brain is occupied with the same task, maneuvering the bike, but it is automatic, non-memorable activity. Then you see a flicker of something, a snapshot, a vivid image. An abandoned church and cemetery in the middle of a median strip, traffic hurtling by on either side. A restaurant in the shape of a giant fish, mouth open. Fiberglass sculptures of blue herons, standing 6 feet high on a street corner, where? There’s no context, the images stand alone. I know only one person who can recite a motorcycle ride in exact order.

Lesson: Don’t pack for conditions at home (we’d left in 97-degree weather). Pack for everything. Shopping on the road is not a trustworthy option.

Day Five: The sunrise enters the motel room like a nail. It is cold. I joke about scraping ice off the bikes. We breakfast in Hinton, a boomtown on the edge of the Canadian Rockies. The foyer has a weird set of public service ads, asking patrons to Cage Your Rage. Tense little scenarios suggest reasons to avoid barroom brawls, to quell the impulse to take it outside.

Maybe it’s a promotion for a local cable TV show. Don starts a conversation with Chris, a local rider who is heading the annual Toys for Tots ride later that morning. He has a Harley Road King, a Ducati and a couple of Nortons. He tells us that beyond the trees there is a network of roads to oil exploration sites, natural gas pipelines—that is a minor city. The past summer 1,000 workers had lived in a tent city. That probably explains the posters.

Outside of Hinton we catch our first glimpse of the Canadian Rockies, an arc of snowcapped peaks that cover a third of the horizon. Snowcapped. In September. Yikes.

We’d had days of wheat, of wings, of weather, now we enter a day of rock and ice.

The Icefields Parkway threads a valley between the eastern and western Rockies, 140 miles of wild rock sculpted by glaciers, frost, wind and rain. The road barely demands attention, which is good. I feel I am moving down the aisle of the world’s biggest big-box store. To the east are a series of overthrust mountains, steep sloped on one side, almost vertical cliffs or escarpments on the other. To the west are dogtooth mountains, rock turned on its side to form spikes and spires. Sawtooth Mountains with spires separated by gullies. Castellated mountains—the so-called layer-cake mountains that resemble buttresses and towers. And horn mountains sculpted on three sides by glaciers. The mountains are raw, wilder than anything in the Colorado Rockies.

We see bighorn sheep and a stranger form of wildlife. A man in a suit sports a bike helmet with a flashing red light. He sits atop a unicycle, pedaling his way through the park. OK….

We buy necessities in the totally cool town of Jasper, continue past the retreating Columbia Ice Field, travel beneath the Bow Glacier hanging above a lake, before ascending a spectacular mountain pass to our overnight in Golden.

Lesson: Stop counting the days.

Over coffee Don notes, “Yesterday I was riding on rock. It didn’t feel green. Today is green.”

I’d noticed the same thing. The mountains have receded behind pine trees. The river winds through a valley that is blatantly fertile.

We ride Route 93 along the flank of the western Rockies, past farms and cattle ranches, logging operations and golf courses. One of the reasons we travel is to see road signs you don’t find at home. We pass wildlife signs with silhouettes of caribou, deer, moose, elk and bighorn sheep. We encounter a sign of a car hitting a moose, with the warning that we are entering a “High Impact Zone.” Another sign warning that pictures of wildlife mean “Caution, stupid.” For all the warnings we see only cattle, not wildlife.

In Radium Springs we stop for caffeine and warmth at the Meet On Higher Grounds coffee shop. A waitress who looks like Mother Nature serves us an organic treat that has all the ingredients of a bird feeder, plus molasses, and is divine. We talk to a couple of ridiculously fit hikers, wearing shorts, who support our plan to abandon 93 for the Crowsnest Pass toward Waterton-Glacier National Park.

We traverse a high plateau covered with golden fields, stark white wind generators and fever dream images of the Wild West—rust-red iron silhouettes of cowboys calf roping, herding rust-red cattle, and rust-red Indians tending rust-red fires, rust-red rodeo hands riding rust-red horses.

We cross into the United States at Chief Mountain Pass, 10 minutes before closing. In Babb and St. Mary’s the no vacancy signs glare red. Is this adventure or bad planning? We turn down the chance to rent a presidential suite for $475 at St. Mary’s Resort, but luck out, nabbing a guest cottage for $175.

Lesson: When your destination is a national park, ignore lesson one. The nearest towns will be booked with overflow. There is no end of season. After the kids go back to school, or leave the nest, Baby Boomers and foreign tourists—not to mention the guys who can’t find their way home from Sturgis—flock to the West. Make a reservation.

The next morning Don waylays a driver of one of the restored vintage tour buses that crisscross Glacier National Park. The red ignites the morning. He tells us that the director of the park came in with a handful of mountain ash berries and said, “Paint the buses this color.”

We head up Going-to-the-Sun Road, stopping every few miles to contemplate a glacier-carved peak, the fall of light on a dark-blue lake, the feel of the day.

We crest Logan’s Pass and see the interior of the Rockies in all its glory. The Garden Wall, a huge face of rock, curves to our right. Before us lay peaks with glacial cirques clawed in the flanks. The Highway to the Sun traces a line down the Wall, beneath waterfalls. Mountain goats are stark white against the shadows. We descend, only to stop, turn around and repeat the experience. The namesake glaciers may be gone, the artists having signed their work have moved on. What’s left is silence and awe.

After so much beauty, Kalispell, the western portal to Glacier, strikes us as a grotesque collection of strip-mall franchise clutter. We ride south into smoke. Montana is on fire.

Lesson: If you peak first thing in the morning, don’t be surprised if it goes downhill from there.

Wisdom: At a coffee stop in Suly we meet a resident of Wisdom. He tells us the town has a population of 65. About a third male. Three single women. Three restaurants. A gas station. A general store. It’s a great place to live, although he has to travel as far as 300 miles to find work.

Lewis and Clark passed this way, and after surviving a particularly hellish series of passes, decided to name three convergent rivers after the qualities of Thomas Jefferson, their sponsor. Of the three—Wisdom, Philosophy and Philanthropy—only Wisdom stuck.

We ride through a valley cut by the Bitterroot River, in a haze of smoke that makes the world as claustrophobic as the inside of a light bulb. Every store and gas station has a sign: Thank you firefighters.

We reach Wisdom a little after noon. Our waitress at Fetty’s is a delight—young, blonde, talkative. She moved to the area from Seattle/Tacoma after her apartment was broken into on her 21st birthday. She loves the town. She never locks her door. She knows everyone in the valley. There is no television or cell phone service, but she doesn’t mind. She’s found a place where her four-year-old son can excel.

That is the lesson of Wisdom. On the ride out of town a bald eagle swoops out of the sky and escorts us, no more than 100 feet away. We ride west, then south, following the winding Gallatin River into West Yellowstone. A day of highways designed and guided by rivers.

Lesson: Wisdom exists.

We enter Yellowstone. At Fountain Paint Pot we listen to the earth turn water to steam, a sound of jet engines. We watch geysers pulse and burble. We sit with others and wait for Old Faithful to do its thing, with far less vigor than anticipated.

We pull off the highway and sit by a river watching fly fishermen work their way upstream. Close your eyes and you can re-create the river by sound. To the left, the slap of water over a submerged rock. In the background the sizzle of water cutting into the far bank. In the foreground, the collapse of a standing wave. The gurgle of smaller waves over a gravel bar. The sounds are spatial, like a musical score or memories of a great ride. This one.

We turn at Mammoth Hot Springs and follow the Lamar River out of Yellowstone, past herds of bison, the occasional elk and deer. This has to be the most tranquil valley on Earth.

In Cooke City we have lunch at the Prospector Grill, and glean info from other travelers. The motels are booked at all the major cities in Wyoming, but the Beartooth Hideaway in Red Lodge has plenty of rooms available.

Red Lodge was a boom town, home to cattle barons, sheepherders, gamblers and coal miners. At one point, the town had 20 saloons. In 1924, when the mines started to close, locals turned to making bootleg liquor. In 1931 a local doctor came up with the idea of building a “high road” into the Beartooth Mountains, something that would connect Montana to the tourist traffic visiting Yellowstone. Like the Going-to-the-Sun Road, and the Icefields Parkway, the Beartooth Highway was Depression-era make-work. Inspired, miraculous makework, completed in 1936.

We enter from the Wyoming side, climbing a series of switchbacks through grassy meadows and pine forests. A scenic turnoff allow us to contemplate the Absaroka-Beartooth Mountains. It is a view that will suck your lungs out. It’s just the start. The road continues higher, past a series of alpine lakes, dark blue against green. What can only be called tundra rises against a single stone peak. Unlike any road we’d traversed, this one holds nothing back. It takes us over the top, across a beautiful plateau. At 10,947 feet above sea level, the second highest road in America.

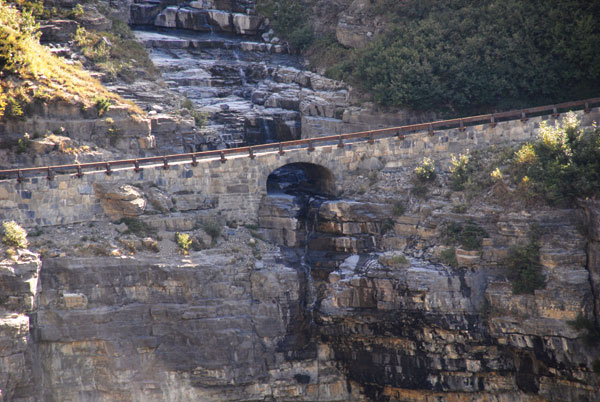

I think: The road has us and will not let go. My heart is somewhere outside my chest, my lungs have forgotten how to breathe. Once again, the earth falls away. We find ourselves on the edge of a narrow valley, a canyon a mile deep, filled with sunlight and haze. The road descends one side of that void, a series of switchbacks that are dizzying—although separating that feeling from the overall awe is difficult. Steel nets line the road to slow falling rocks. The BMW RT is a hawk, claws extended, in full plummet.

When we reach the valley floor a moose, black coated with golden-brown antlers, lopes alongside the road, keeping pace.

That night we celebrate with an elk and trout dinner at the Carbon County Steak House, essentially, wonderfully whipped.

Lesson: Know when the trip is over.

The next morning we chip ice off the bikes and head home. The cold front creates a cleansed sky that will last two days.

Spearfish. The Badlands. Grassland turning to corn fields. Rows of plants packing heat, green holsters mid-stalk. Silos silver in the sun. Wind turbines as white as the future. Weird sculptures in the middle of wheat fields. A huge billboard advertising microsurgical vasectomy reversal (such a large sign for such a small operation?). A team of paragliders spiraling above a county airport. Crossing the Mississippi, recognizing the familiar.

Four-thousand, six-hundred, sixty-two miles. Wiser for each one. Home.