Slogging on foot for days through deep snow on unmarked mountain trails with little to eat isn’t anyone’s idea of fun, but that’s how Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery crossed Idaho 200 years ago.

We did it a much better way—in summer by motorcycle—yet still gained a deep appreciation for the explorers’ journey. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were commissioned by President Jefferson to find a river route from the Midwest to the Pacific Ocean. Combining adventure, adversity, danger, endurance and ingenuity, their three-year odyssey from 1804 to 1806 is the ultimate U.S. road story. There’s even a woman: Sacajawea is getting due recognition, particularly for the Idaho portion of the trip, thanks to the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial celebration.

Indeed, the Idaho crossing was the most hazardous segment. Beset by early snow and near starvation, the men came close to dying here. They stayed alive by eating a colt, bear’s oil, candles and a hated broth they called “portable soup.” Remarkably, two centuries later, the trails and campsites the corps used and the vistas it saw remain just as they were back then, only now easily accessible by motorcycle.

You can camp in the same grassy meadows along the trail (Forest Route 500) and sit in the same hot spring water (Lolo Hot Springs) they did. And from the top of Lemhi Pass, you can straddle the headwaters of the Missouri River and gaze on what Lewis called “immense ranges” that had yet to be crossed. The plants, smells, sounds and alpenglow of the setting sun on the mountains are the same. You’re just traveling in more comfort if you’re on a bike.

A Dual-Sport Journey

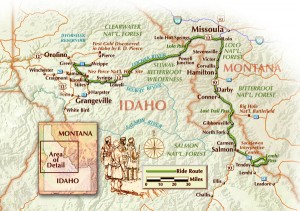

We rode our Kawasaki KLR650s to retrace the Corp of Discovery’s journey through Idaho in September 1805 so we could experience the rugged back-country trails the explorers trekked on, as well as the paved highways paralleling them. U.S. 93 north from Salmon, Idaho, to Lolo, Montana, and then west on U.S. 12 through Idaho, is the parallel trip. These asphalt roads are relaxing to ride, with numerous motels, campsites and restaurants ready to accommodate visitors. Passing through gorgeous country and offering many sweepers, U.S. 12 is surely one of the best rides in America.

The actual trail Lewis and Clark walked is now a 119-mile forest road called the Lolo Motorway. Passable from June to September, it’s a primitive, rocky single track with no services or facilities. To ride it, you may need a permit from the U.S. Forest Service. You’ll also need a dual-sport bike, food, water and camp gear because you’ll be on your own. No Starbucks here.

Historian Steven Ambrose described this terrain as “still basically uninhabited” and unchanged two centuries later. We were completely alone in our campsite atop the Bitterroot Mountains. We watched the stars put on an amazing light show and listened to the wind rustling in the pines just as Lewis and Clark’s men must have in 1805. The big difference was our trusty motorcycles looming in the darkness and the occasional satellite crossing the heavens.

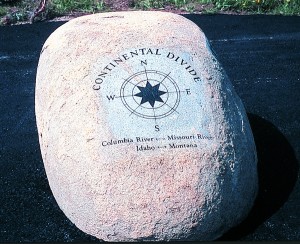

An additional gravel road that riders can enjoy is the Lewis and Clark National Back Country Byway. This takes you up to Lemhi Pass on the Montana-Idaho border, where the explorers first crossed the Continental Divide and met the Shoshoni Indians—Sacajawea’s relatives—who would provide the horses needed to cross Idaho. This is a well-graded road that’s OK for road riders (we know because a Gold Wing was heading down as we rode up).

Salmon and Lemhi Pass

We started our trip in Salmon, a recreation gateway to Idaho’s roadless wilderness. Take Idaho 28 one mile southeast and park your bike at the brand-new Sacajawea Interpretive Center. When we visited, it was so new that the exhibits were still unfinished. Sacajawea was kidnapped by another Indian tribe while still a young girl. In her early teens, she married Lewis and Clark’s French trapper guide, Charbonneau. The center’s crowning glory is a life-sized bronze statue of Sacajawea and her newborn son, Jean Baptiste or “Pomp,” by Idaho artist Agnes Vincen Talbot. Be sure to walk the nature trail, where you’ll see sculptures of soaring eagles and leaping salmon and learn about the Lemhi Shoshoni.

The 39-mile National Back Country Byway is a loop road that starts 28 miles southeast of Salmon on Idaho 28 near Tendoy. Stopping at the Tendoy Store at the start of the byway for a souvenir or cold soda is a must. The store’s operator for the past 56 years, Viola Anglin, is a landmark herself and serves as an ambassador for the Forest Service. She’ll greet you like a long-lost friend and tell you everything—and then some—about Lewis and Clark and local history.

The byway, which begins as Warm Springs Wood Road, twists and turns through open sagebrush-covered terrain and lodgepole pine forest. Three big-horned sheep watched us take a curve on our way to the 7,373-foot elevation of Lemhi Pass. If you bring a bathing suit and pay $1, you can soak in the mineral waters at Starkey Hot Springs near the beginning. Changing rooms are available, but don’t forget to pay on the way in or you’ll owe $5 on the way out (you’re on the honor system here).

A plaque marks where Lewis unfurled the American flag for the first time in Idaho. The view is breathtaking, with mountains stretching to the west as far as you can see. You can easily imagine Lewis telling Clark: “That’s it, Bill. I quit. My moccasins will never last over those mountains, and the mosquitoes are eating me alive!”

The explorers needed to find the Lemhi Shoshonis and buy horses. That’s where Sacajawea comes in. When the corps met the Shoshonis at the top of Lemhi Pass, the Indians were suspicious of the group’s motives. But Chief Cameahwait turned out to be Sacajawea’s brother, and the two had a touching reunion. After that, Lewis and Clark were able to trade for the horses and continue their trek west across the mountains.

The byway takes you over the Continental Divide. Just below Lemhi Pass on the east side, the Missouri River begins flowing east. You, too, can straddle its headwaters just as one of Lewis and Clark’s men did. It’s cool up here, and we enjoyed a peaceful picnic and heard an elk bugle as we soaked up our Lewis and Clark experience.

To complete the byway loop means descending a steep hill leading to Idaho 28. It’s an ungraded road, with loose rocks and gravel, so it’s best for road riders to go back the way they came. All totaled, riding the byway loop takes several hours, depending on how long you linger at each point of interest.

After a hard and strenuous day crossing the divide, we sat down to an excellent dinner at the Shady Nook Restaurant in Salmon, where prime rib and fresh trout entrees are $15-$20. In the morning, we joined the locals for an inexpensive but hearty breakfast at the Salmon River Café and Restaurant on Main Street.

North through Montana to Lolo Pass

For a short time, Lewis and Clark hoped the corps could float down the Salmon River to the Columbia River, which would take them to the Pacific. But they quickly discovered the “River of No Return” was too treacherous. So at present-day Salmon, they started their trip north over what’s now called Lost Trail Pass to the Bitterroot Valley of western Montana.

Lost Trail Pass gets its name because Lewis and Clark and their guides lost their way here. We had it a lot easier—U.S. 93 is newly paved two-lane in each direction, allowing for easy passing as you ride up to 7,014 feet in elevation and cross the Continental Divide for the second time. In Montana, U.S. 93 passes through Darby, which could easily serve as a set for a Western movie because of the wooden facades and Western feel of its buildings. By now, you may be hungry. If so, hold out for home cooking and great pie at The Coffee Cup a bit farther north in Hamilton, Montana.

Gas up where U.S. 12 meets U.S. 93 at Lolo, since there are few gas stations ahead. It was late September when Lewis and Clark came through these parts and winter was coming. Although the steam was rising when they arrived at Lolo Hot Springs, 25 miles west of Lolo, they didn’t linger. Nowadays, the hot springs are a local resort, complete with campground, motel, saloon, restaurant and soaking pools.

A new log-cabin-style visitors’ center at the top of Lolo Pass (elevation 5,233 feet) marks the beginning of the explorer’s 10-day march west in September 1805 (and the end of their six-day return trip in June 1806) on what the Indians knew as the Trail to the Buffalo or Nee-Me-Poo.

Here’s where the two routes—the rugged mountaintop trail the explorers walked, called the Lolo Motorway, and the paved U.S. 12 paralleling it—diverge. U.S. 12 is clearly the choice for the majority of riders. Even if you don’t give a hoot about Lewis and Clark, don’t miss this highway. The road runs along the north side of scenic Lochsa River for 77 miles, boasting sweeping curves and beautiful views of the roadless Selway Bitterroot Wilderness on the south side of the river. Stop and put your toes in the pristine water, fish for a while or take a nap at a rest stop, as I did.

Another rest point is the Syringa Café, which offers upscale local fare, such as salmon and elk, and other dishes. We savored the day’s featured entree, shrimp and crabtopped prawns, and then slept soundly at the Reflections Inn, a bed and breakfast on U.S. 12 about five miles west. Innkeeper Ruth May is the local Lewis and Clark bicentennial coordinator and can fill you in on what’s planned for the region.

The Lolo Motorway

Two centuries earlier, on the high mountain ridges, the corps weren’t eating anything remotely as delicious. They were trudging, step by soggy step, through deep snow that began falling soon after they started out. Most days, horses fell or had to be killed to keep the group alive. “I have been wet and cold in every part as I ever was in my life, indeed, I was at one time afraid my feet would freeze in the thin Mockierons which I wore,” Clark wrote in his journal. Five days into the westbound trip, the men had only bear’s oil, their despised portable “supe” and 20 candles for dinner. “Ugh, candles again….”

Clark and a few men walking ahead were the first to emerge in the prairie near Weippe, followed by Lewis and the rest of the starving band. Fortunately, they quickly encountered Nez Perce Indians who gave them food. The Indians told them that the Clearwater River in the next valley would lead to the Columbia River, which flowed to the Pacific. While recovering from their mountain ordeal and dysentery caused by gorging on salmon, the explorers made camp along the Clearwater and built the canoes needed for the final push to the ocean.

Our dual-sport ride along the Lolo Motorway, a National Historic Trail, was less eventful. Forest Road 500 is hard-packed dirt and gravel in places, sandy and rocky in others. Fire has caused the road to erode, so we stayed away from edges where the drop was sheer. Informative signs describe each of the explorers’ campsites heading west and then east again. In this remote terrain, it’s easy to feel the presence of the hardy travelers. I marveled at their endurance and wondered how they avoided frostbite. But I didn’t feel too guilty while eating chicken and pasta cooked on a one-burner stove, followed by fruit and hot tea and a comfortable night on an air mattress.

Weippe’s Moment in the Sun

The motorway stretches about 119 miles, but we left it after about 70 miles to rejoin U.S. 12. We rode the pavement west along the Clearwater River to Greer, turning north on Idaho 11 and taking a series of steep switchbacks to the prairie above. At Weippe, signs directed us along a dirt road to where Lewis and Clark emerged from the mountains and met the Nez Perce. The bicentennial celebration is putting Weippe (population 375) on the map. Dozens of expedition followers sign the visitors’ book each week. One couple noted they were retracing Lewis and Clark’s trip by ultra-light plane. And we thought riding motorcycles was unique!

In the big scheme of things, Lewis and Clark weren’t very successful in locating an easy westerly route. Still, few have surpassed their courage, endurance and bravery. If you like good road stories and great rides, retracing their journey through Idaho is among the best.

For permits to travel the Lolo Motorway, visit www.fs.fed.us/r1/clearwater/LewisClark/LewisClark.htm.

(This article Idaho Crossing: Riding with the Ghosts of Lewis and Clark was published in the June 2005 issue of Rider magazine.)

|

|

|

|