The road curves gently, the pavement is smooth, tall trees on both sides bring shadows to this two-lane byway. The grass along the sides has been trimmed in the not-too-distant past, and clutches of bright blue, red and white flowers dot the occasional field. Yellow black-eyed susans are very much in season.

No billboards intrude on my reverie, no stop signs, no chrome or neon fast-food signs, not even much traffic. Maybe I see one car every couple of miles. The Guzzi is in fifth gear, and we are barely ticking over at 2,500 rpm, as the local limit is a modest 50 mph. Not that I mind—I’m cruising, I’m traveling, with no rush to get anywhere special by any time.

This is a ride I’ve done before, and I’m sure I’ll do again. I won’t see a commercial vehicle while I’m on this road, not even one stoplight, and only a single gas station. The occasional horse will look over a fence at my passing. This is good traveling for a troubled soul, because it tells the rider that all can be right in this complicated world.

My soul’s not troubled, but I do love this ride. It reminds me that not every place is taken up with housing developments, shopping malls and crowded streets, nor that one has to roll along an interstate at 80 mph plus. As one of those 1950s songs said, “Take it slow, and, Daddy-o, you can live it up and die in bed.” If there were Burma Shave signs along the side of the road, I might think I had been transported back to the Eisenhower years.

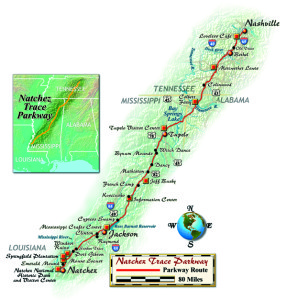

What is the purpose of this stretch of uncommercialized two-lane blacktop that runs through Tennessee, nips off a corner of Alabama, and then cuts diagonally across Mississippi? It is on-the-road history, celebrating everything from the westward expansion of the new American republic back in the late 1700s, to solutions for the Great Depression of the 1930s.

You may not have heard of the Natchez Trace, but it’s been around for over two centuries, which is a fair bit of time considering the age of this nation. Today the Natchez Trace Parkway is maintained by the National Park Service and the longest, skinniest park on the map, more than 400 miles long and averaging less than a quarter-mile wide.

I had been staying with friends just south of Nashville, Tennessee, aiming for the Pacific Ocean. I could keep on going due west, but Jim convinced me to take a 450-mile jog to the southwest, down the Trace. That might take an extra two days, but well-spent days they would be. Jim took me to the Loveless Café for breakfast, which is at the northern end of the Trace. The place has been serving up redeye gravy with homemade biscuits for over 50 years, sure to satisfy the strong of constitution. I fill the Guzzi up at the gas station next door, and I am away.

The Trace is not just a road, it is a strip of Americana, and all along the way are places to pull off and think about the men and women who built this country. Like down by the Duck River, where one John Gordon ran a ferry service. Back in 1801 the local governments did not have the money to build expensive bridges, and most river crossings had some enterprising type who would boat you over for a nominal fee. The Gordons were pretty successful, and built a big brick house that still stands—although the colonnaded wooden double-decker porch has disappeared.

This is all flattish southern land, gentle hills rising between the river valleys. A small sign indicates a stop where one can see the Old Trace. Park the bike and walk along a narrow alley through the trees. This is where the story begins.

In the 1770s the Brits did not want the colonists to go beyond the eastern seaboard, as they feared they would lose control of their citizens. But after 1783 the new Americans began crossing the Appalachian Mountains and settling in Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee, raising pigs and making whiskey. But where would they sell their goods? Taking it back across the mountains was prohibitively expensive, so the solution was to build a flatboat, load it up and float down the Cumberland and Ohio and Mississippi rivers to Natchez. At this trading post buyers would pay fair money, even for the wood from which the boat was built.

Then these farmers would head back home from Natchez to Nashville, along the Trace; most of them went on shank’s mare, which means on foot; a few bought horses. From 1785 to 1820 thousands of men passed along here, each footstep compacting the soft earth a little more.

If a man were in good health, the 450-mile trip would take a month. Some never made it, like Meriwether Lewis. The Guzzi and I pull in to the site of Grinder’s Stand—a “stand” being the Trace word to describe a place where a traveler could get food and maybe a porch to sleep on. Lewis, head of the famous Lewis & Clark expedition that explored all the way to the Pacific Ocean between 1803 and 1806, was made governor of the Louisiana Purchase in 1807. Two years later he was headed to Washington for some business; he stopped at Grinder’s, and ended up dead. The shot that killed him was probably self-inflicted, since he was known for his depressed moods, but others maintain it was murder. We’ll never know for sure. A truncated column commemorates his short life.

Guzzi and I roll on, miles and miles of calm beauty. We cross the Tennessee River, where a fellow named George Colbert ran a ferry service. It is said the U.S. government paid Colbert $75,000 to ferry Andrew Jackson’s army across in 1814, when Jackson was on his way to New Orleans to beat the Brits. That’s history.

Arriving in Tupelo I stop at the Natchez Trace visitor center, and then head off to the east side of town to have a gander at the birthplace of Elvis Presley. That’s a damn small house he was born in, and where he spent his childhood. A bronze statue of a 13-year-old stands outside, and a museum and gift store—emphasis on the gifts—is being enlarged. The place is much nicer than Graceland.

I sleep in Tupelo, leaving early the next morning with a full tank of gas. Seventy miles down the road is the Jeff Busby Site, and old Jeff is the person responsible for this wonderful trip. He was a U.S. Congressman in the 1930s who convinced President Roosevelt that building a road along the old Natchez Trace would be a great way to employ a lot of jobless people…this being the Depression and all. Good thinking; my helmet is off to Representative Busby.

Ten miles farther is French Camp, a collection of old buildings and farm equipment, and a little restaurant that serves the bestest, biggest BLT I’ve ever had—with 10 rashers of bacon. Wowzer!

I’m barely touching on all the places to see along the Trace. I stop at Cypress Swamp, where a boardwalk leads me through the tupelo and cypress trees, safely above the murky waters. No alligators here, I am told, but you never know. Guzzi and I cruise alongside the Pearl River, which has been dammed to create a large reservoir, where anglers are trying their luck.

A small crafts center is sited at Mile 102, full of handmade products like carved cherrywood spoons, woven baskets and all the essentials that families made themselves before there was a Wal-Mart down the road. Here the Trace temporarily ends, and the Goose is subjected to 15 miles of 80-mph interstate as we bypass Jackson, the Capitol of Mississippi. All the traffic and trucks and big signs make me aware of how very, very nice the Parkway is to ride. The crafts lady tells me that they are working on completing this portion of the Trace, and it should be done in 2005. Maybe, maybe not.

The Trace Parkway begins again at Clinton, and as I ride past Raymond and on to Port Gibson I’m in Civil War history. Union General U.S. Grant swept through these parts in the spring of 1863, in order to attack the important river city of Vicksburg from the east; the Vicksburg garrison surrendered on July 4th, 1863, the same day that General Lee ordered his Confederates to retreat from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Two such defeats in one day! The Confederacy was doomed.

At Port Gibson I leave the Trace for 10 miles and take Mississippi Route 552 instead, because I want to see the ruins at Windsor Plantation. The house was said to be the largest in the state, and survived the Civil War, only to fall victim to a careless cigarette in 1890. All that remains are 24 very tall columns, an eerie and impressive sight. Back on the Trace we come to Mount Locust, a reconstructed stand and farm, that lies less than 25 miles from Natchez. The farmer would see these boatmen trudging north, and some would ask if they could buy a meal. Soon it became a profitable sideline, providing food and giving bedroll space to these homebound fellows who always had money to pay, as they had just sold their goods.

The Trace Parkway ends by merging into U.S. 61 eight miles north of its official beginning on the Natchez bluffs above the Mississippi River. That stretch, too, will be finished one day—but nobody gave me a date.

Natchez has to be one of the most attractive small cities in the country, where many antebellum mansions are well maintained. Down on the riverbank, or “under the hill” as they say, gambling (on a riverboat) and drinking still continue, though not quite as rambunctiously as 200 years ago.

I think Guzzi and I will head back “on the hill” and ride over to Prosper King’s Tavern, in business since George Washington was elected president. There I will order up a plate of a dozen oysters to celebrate one of the nicest cruises I have ever had, more than 400 miles of beautiful two-lane road without so much as a stop sign.

(This Two Lanes of American History article was published in the November 2003 issue of Rider magazine.)