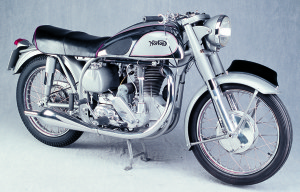

Norton was never one of the larger English motorcycle factories, but for over 70 years, wherever there was racing, there were Nortons. The Norton International is the street version of one of the best racers ever built, the Norton Manx, and shares the Manx’s handling qualities and gorgeous good looks.

James Lansdowne Norton was born in Birmingham in 1869. Apprenticed to a jeweler, he started his own bicycle parts business in 1898, but soon became interested in motorcycles. He was always a pioneering engineer, and the first Norton, built in 1902, had a two-stage countershaft transmission. These early Nortons were powered by Swiss and French engines. A French Peugeot twin powered the Norton that won the first Isle of Man TT, held in 1907. Norton commenced building his own engines soon afterward.

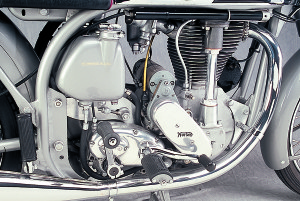

The TT win was followed by other racetrack successes, and the company became known for its production racers. In the 1920s, Norton hired Walter Moore to design an overhead-cam engine that was intended to power both a racer and a sport motorcycle. This 490cc engine was not quite perfect, and was redesigned in 1930 by Arthur Carroll.

A motorcycle powered by one of these overhead cam engines won its first race, the 1927 Isle of Man TT. By 1929, Norton was selling the sporty but street legal CS1 (Cam Shaft One). The first supersports Internationals appeared in 1932, powered by the Moore single-overhead-cam engine. They were more race-oriented than the CS1, and came in 348cc and 490cc versions. Most were built with lights.

Although the first Internationals had single-leading-shoe brakes, girder forks and a rigid rear section, Norton also incorporated a four-speed footchange gearbox, which was very innovative for the time. Hairpin valve springs appeared in 1935. These were hard to enclose, but less subject to breakage at racing speeds, as valve-spring steel was not anywhere nearly as good then as it is now. If a hairpin spring did break, it could be replaced in seconds.

In 1934 or 1935 Norton cataloged a pure roadracing version of the International, informally referred to as the “Manx model.” Plunger rear suspension appeared in 1938. Development stopped in 1939 when World War II ended racing, among many other things, for the duration.

Norton was able to recommence building the overhead-cam engine in racing form, now named the Manx, in time for the September 1946 Manx Grand Prix, but the street-legal International did not return until 1947, when it appeared in both 500cc and 350cc sizes. The first postwar Internationals had a cast-iron head and cylinder instead of the prewar alloy top end, and telescopic forks. Otherwise, they were very much like the prewar model. An Amal TT carburetor fed the engine, and a Lucas magneto/generator combo (called a magdyno) supplied spark.

The postwar version of the International sported a closeratio gearbox (similar to the racing box, but with gears for a kickstarter) and a “garden gate” plunger frame. Most Internationals were bought as clubman racers, and they racked up wins in amateur events.

It was 1953 before Norton significantly upgraded the International. The chassis was changed to the superb-handling Featherbed swingarm frame, similar to the one used from 1950 on the factory Manx racers. The top end became aluminum alloy and the muffler was now the stock unit used on less sporting Nortons.

Although the International was one of the best-looking of ’50s motorcycles, it was rapidly becoming obsolete. BSA’s Gold Star was cheaper to buy and easier to work on, and most non-racers were buying twins. The last Internationals were built in 1958.

In recent years, the desirability of Internationals has skyrocketed. The combination of a roadgoing version of the Manx overhead-camshaft motor with the International’s classic good looks has great appeal for collectors, and their comparative rarity does not hurt. Paul Adams located this bike in Oklahoma City in 1979.

“I’ve always liked Nortons, and I liked the idea of an overhead-cam street motorcycle. That meant an International. The one I bought was really unoriginal—it had been used as a racer. The engine, the gearbox, the frame, the oil tank and the rear wheel were OK, but the rest was wrong, really wrong. I took it home and got it running, but then got busy with other projects and wound up storing it for years.

“Four years ago, a friend, Dick Newby, wanted me to restore his 1956 International. I thought that it would be easier to restore both Internationals together, and that gave me the motivation to restore mine. It turned out I was wrong—it took almost as long as it would have to restore each bike separately. The one advantage was that I only had to mix up one batch of paint.”

By the time Adams got around to restoring his International, he had accumulated a good stock of International parts, and most of what was missing or wrong could be replaced with correct parts from his shelves. “I didn’t have to find much,” he admits. “Just raided the junk pile.”

Dick Newby did the tracking down and ordering of the few parts that Adams didn’t have, leaving Adams to concentrate on disassembling the engine, truing the flywheels and replacing all the bearings. The International’s crankpin has a slight taper. The mechanic presses the pin into the flywheels and draws it up with large nuts that must be turned with a special tool.

After machining the valves and valve guides and setting up the mesh of the bevel gears and the tower drive for the overhead cams with proper clearances, Adams moved on to the gearbox. The three higher gears in the International box are the same close ratios as the Manx, with a large gap between first and second gear. Unlike the Manx transmission, the International transmission is set up for a kickstarter.

At some point in its history, Adams’ International had been very wet. As a result, the frame and sheet metal were badly pitted. “I had to strip and bead blast it all. I got brushable Bondo, recommended by a friend with an auto body shop, to fill the surface pitting. It took hours just to fill and sand the frame. Even the instrument panel was pitted.”

The exhaust system came from a specialist in England, but despite promises, it didn’t fit. Paul ended up cutting it up, modifying it, welding it back together and sending it out to be chrome plated.

Now restored, Adams enjoys riding the International. “Overhead-cam Nortons start easily. The secret is having a good magneto. I always tell people that if they are serious about riding their restoration, get the mag rewound. Starting the bike becomes fun, instead of a chore. Ninety percent of all vintage starting problems are due to old magnetos, and most of the rest are due to dodgy carburetors.

“You can rev to 6,500 rpm, but I ride my International conservatively. It doesn’t have a tach, so I shift by ear. These things have a ton of torque, so staying in the powerband is not a problem.

“It’s happy cruising at 60-65 mph, but it really likes twisties, all sorts of twisties. It is a delight on twisty roads. This Norton has no more vibration than any other 500cc single. With the overhead cam, you get more positive valve opening and closing. The balance factor of the lower end is set so that it is smoother at higher rpm.

“It’s a thoroughbred engine in a thoroughbred frame, and it’s street-legal. It’s also one of the prettiest bikes that I own.”

1953 Norton International

ENGINE

Type: Upright single cylinder

Displacement: 490cc

Bore x Stroke: 79mm x 100mm

Compression Ratio: 9.0:1

Valve Arrangement: Single overhead camshaft, two valves per cylinder

Carburetor: 13⁄16-inch TT Amal carburetor

Transmission: 4-speed, right foot shift

Clutch: 3-spring multiplate, oil bath, hand-operated

Lubrication: Dry sump

Final Drive: Chain

CHASSIS

Frame: Featherbed cradle frame

Wheelbase: 56.5 inches

Seat Height: 31 in.

Suspension, Front: Roadholder telescopic fork

Rear: Swingarm, dual Woodhouse Monroe shock absorbers

Brakes, Front: 8-inch single-leadingshoe, half width of wheel

Rear: 7-inch single-leading-shoe

Tires, Front: 3.00 x 19 in.

Rear: 3.25 x 19 in.

Dry Weight: 350 lbs.

ELECTRICAL

Ignition: 6-volt magneto/generator combination (Lucas magdyno)

Charging System: Generator (Lucas magdyno)

PERFORMANCE

Fuel Capacity: 4.8 gals.

Oil Capacity: 8.4 pints

Horsepower: 29.5 @ 6,500 rpm (factory rating)

Top Speed: 100 mph (owner estimate)

The article Street Manx was published in the May 2003 issue of Rider magazine.)

I enjoyed looking and reading about your Inter. I have been lucky enough to have had 2 Inters, a 1952?? 350 and a 1955 500, colour black.

My 350 was a works Inter I was told by the seller, and had a brass TT10 carby and when I took the head off I was surprised to find that the head was bronze with alloy fins cast over it. I have mentioned this to other people and have yet to find anyone who knows anything about this type of cylinder head. I would appreciate your help in replying if you have heard about these heads. The valve overlap was huge, the engine would not run under about 800 revs and would run backjwards if I tried to run slower.

Regards Robert

My 1953 had bronz do.me head and an Alfin barrel also reputed to be a works clubman racer.