Most states extend the welcome mat. In former times, upon entering the Sooner state on eastbound Interstate 40 and passing the stoic Oklahoma sign, a traveler first noticed the posted speed limits, followed by the fines listed in five-mph increments for exceeding said limits. Picketed alongside the freeway margin like a nightmarish Burma Shave scenario were additional warnings, one proclaiming, “Strictly Enforced,” punctuated by a separate final edict: “No Tolerance!”

What a difference 15-plus years make. Now a new, decorative granite sign demarcates the state line, followed soon by a billboard depicting a Buffalo Bill character, waving his Stetson, astride a spotted horse rearing out of the sign in welcoming exhortation. A few miles farther along I encountered a staffed welcome center amidst a shady park. I took advantage of the free maps and coffee. Later, the only cops I saw actually waved. The posted speed limit permitted me to go 75 mph.

Relaxed and filled with hopeful anticipation, I felt it appropriate to make my next stop the Route 66 museum in Clinton. This so-called Mother Road became the highway of opportunity for Depression-era Oklahoma dust bowl refugees seeking renewal in the agricultural paradise California promised. During the formative period of the motor age, America’s Main Street came to symbolize a restless, free-wheeling mobility. The museum evokes images of evolving roadside culture, represented by dining cars, neon signs, motor courts and art deco architecture. Today I-40 has all but displaced Route 66, of course, and I’d been pounding its stupefying miles for nearly four days to get here. You’d better be worth it, Oklahoma!

I finally left the interstate at the Canadian River and found myself in Hinton, gateway to Red Rock Canyon. Hinton consists of brick storefront buildings facing a main street of angled parking, not only on both sides of the road, but down the middle as well. A bandstand shack with an information marquee sat squarely in the center of the street facing the town’s only intersection. As I photographed the scene from the corner a driver actually slowed to wait until I had finished. A little girl on her bicycle stopped to ask why I was taking pictures. I said I found her town interesting—didn’t she? The tyke shrugged her indifference and rode off.

Near the outskirts of town a steep, hairpin-curved road dropped into Red Rock Canyon, a hidden valley chasm sliced by a spring-fed creek flowing beneath soft, red sandstone cliffs. Climbers rappelled up their sheer faces. I found secluded camping among a fine old grove of hardwood trees. Dawn gleamed brilliantly over the rust-colored bluffs as I rode through a meadow and out of the mile-long ravine.

At Nelda’s Red Rock Café in Hinton I enjoyed a fluffy omelet along with 20-ounce tumblers of juice (under a buck) and water. I was told liquid is served in such tall glasses as a courtesy to help fend off the unrelenting heat. A woman told the waitress that it always rains at the Oklahoma State Fair in Oklahoma City, but not here.

The early morning sky already dripped humidity. Oklahoma had recently suffered, along with Texas, through its worst prolonged heat wave on record. Dried grasses, yellowed wheat stalks and brown trees defined a tawny countryside. State Route 37 softly undulated with the landscape and occasionally curved in sweeping bends through wheat fields steadfastly clinging to baked earth, stalks shaking timidly in the breeze beneath the withering heat. Soon I came across an enduring symbol that has always sustained the Oklahoma economy, despite any erratic weather. A fully operational oil derrick turned and churned inexorably to extract the black, liquid gold that influences world markets and politics.

The speed limit on these country roads is posted a more-than-reasonable 65 mph. Then I plunged from countryside into the cauldron of Oklahoma City, spreading itself in a confusion throughout 600 square miles. It grew this way, as I understand it, because settlers stampeded into the area during the first Oklahoma land rush in 1889. One observer at the time noted: “All I could see was a lot of tents arranged in a haphazard way, much like someone had thrown a handful of white dice out on the open prairie.” A city of 10,000 squatters had sprung into existence before sunset. When oil was discovered beneath the city in 1928 it created another uncontrollable boom, which accounts for the derrick erected and still pumping away on the statehouse lawn. Nevertheless, I found it worthwhile to visit the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and view the extensive collection of Western art.

After the Oklahoma City frenzy I just wanted to find any semblance of mountains the state offered, so I plummeted southward along Interstate 35 until I found myself in the Arbuckles—gentle, time-worn hills surrounding the Washita River. At Turner Falls Park waders splashed in a circular swimming pool beneath the 77-foot cascade. I encountered Route 77D elevating high enough to allow broad views across the Washita River. This whiplash of road led me into Dougherty and the Arbuckle Lake region. More scenic byways whirled around rugged outcroppings encircling the reservoir, directing me eventually to Sulphur and a pleasant surprise.

At Travertine Nature Center I discovered freshwater streams and mineral springs pervading the area, creating cool swimming holes along Travertine and Rock Creeks. A parkland of pavilions, cold pools, cascades, trails, campsites, stone bridges, wending rivulets and winding roads engulf the town. Formerly Platt National Park, the spot is now called the Chickasaw Recreation Area. A ride up Bromide Hill provided an overview of the tree canopy. I camped along rippling Travertine Creek and sought relief from the burning Oklahoma sun by soaking in one of the many terraced swimming holes.

Breakfast at Country Cooking in Sulphur included fried green tomatoes and the essential huge tumbler of iced tea. State Route 7 tiptoed eastward along a geographic edge where upland forest and prairie meet. This Arbuckle region constitutes a transition between the mixed-grass prairie of central Oklahoma and the eastern woodlands. Prickly Pear and yucca grew amongst the oak and sycamore. State Route 3 crossed the divide to Antlers, where I learned this region of Oklahoma was not immune to freakish weather. In 1945 a tornado virtually wiped out the town, heaving 86 luckless souls into the hereafter.

U.S. 271 zipped together the woods, and tugged against the Kiamichi Mountains near Albion, a scene resembling Virginia’s Blue Ridge. State Route 63 threaded the valley until it snagged U.S. 259, and that escalator lifted me atop Winding Stair Mountain. At ridgeline I hopped the Talimena Skyline Drive, a 55-mile-long ribbon intertwining Talihina, Oklahoma, and Mena, Arkansas (hence, the name Talimena, a combination of the two). The road rhythmically rose and fell while twisting along the Ouachita crest, providing constantly shifting watercolor views of distant, layered, blue-tinted ridges.

I followed the wooded valley out of Talihina and turned north on State Route 2, riding in the tracks of the James boys and the Youngers along the so-called “Robbers Trail.” I camped at Robber’s Cave State Park, named for a lair used, according to hearsay, by the likes of Belle Starr and the Dalton gang. Oklahoma makes more of this than what is actually substantiated. But padding the legend draws the tourists.

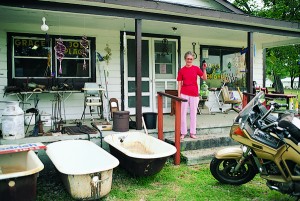

Somewhere outside of Briartown I passed another quirky storefront cluttered with yard sale castoffs, so I turned around and made the acquaintance of retiree Grace Kelly. Grace lives in the back of her converted house, designing crafts for the gift shop, including her popular “whirlybird” whirligigs made from liter-size plastic jugs. Each is a unique art piece, so I found room aboard to strap one of the bottle birdcages. “I just start drawin’ and cuttin’ and paintin’ until I come up with the finished product,” Grace said with understated pride. When I asked about the jumble of odds and ends littering her porch, she giggled a line from Dr. Seuss: “From there to here, and here to there, funny things are everywhere.”

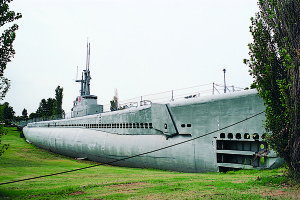

As a former Navy man I undertook a pilgrimage to Muskogee to see an unusual exhibit. At the Port of Muskogee, resting on the grass in permanent landlocked drydock, is a World War II submarine. The USS Batfish sank 14 enemy ships and three Japanese submarines in as many days during her seven war patrols. I’m not old enough to have made a war patrol, but I am the last of a breed, having served aboard a similar diesel submarine during the ’60s.

Oklahoma was essentially Indian Territory until overrun by settlers during the great land rush, and Muskogee itself became a headquarters for the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. In 1874 the Union Agency for the Five Civilized Tribes was installed in Muskogee, and that same building is now a museum.

Relocated Indians often disembarked at Fort Gibson, just outside of Muskogee. The stockade was the westernmost U.S. outpost when built in 1824, and so it provided a staging area for expeditions into uncharted realms. Among the officers stationed here were future President Zachary Taylor, Confederate General Robert E. Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Washington Irving gathered material for a book here. The fort was briefly held by Confederate forces during the Civil War, and a representative soldier reenactor conveniently showed up to stand a relaxed watch in the garrison, stogie in hand.

Fort Gibson was built at the confluence of the Verdigris, Grand and Arkansas rivers, an area known as Three Forks Country. While exploring near Fort Gibson I ran across twin iron truss bridges dating from 1926 spanning the Grand River. These girder frameworks were not unlike the numerous steel spans built along Route 66 to the north. I headed that way over glorious winding, wooded State Route 80 edging Sequoyah Bay.

Historic Route 66 still passes through Claremore, where I spent the night in motel luxury for a change. I had intended to stay at the Will Rogers Hotel, but alas, the historic edifice was only dedicated to the noted humorist and is now a retirement home. Outside of town, however, is the memorial and tomb to Oklahoma’s illustrious son and beloved national figure whose life was cut short by a plane crash in 1935. He rests in perpetuity on a serene hill in his home town beneath a giant statue of himself astride a horse. Etched into the granite above his vault is this pithy aphorism from the cowboy philosopher: “If you live life right, death is a joke as far as fear is concerned.”

Another attraction in Claremore I found interesting was the Davis Arms & Historical Museum. An Oklahoma entrepreneur, John Monroe Davis collected guns for 78 years until he ended up with the “world’s largest privately owned gun collection,” 20,000 of them. Also on view are swords, gunsmithing exhibits, statuary and some 1,200 steins.

I left Claremore and passed through Oologah, Will Rogers’s birthplace. The Bliss Restaurant in Nowata provided another excellent repast with the requisite tumbler of iced tea. I love the community spirit depicted in murals splashed across downtown buildings, and Nowata displayed a representative collage of cowboys, Indians, oil wells and cattle.

With all the country music emanating from various stations on the bike’s radio, it startled me to learn that a Mozart festival is held annually in Bartlesville, and that’s what piqued my interest about the place. Bartlesville is a compact, tidy city of stylized brick skyrises. One architectural deviation from the norm is a glass and copper skyscraper designed by Frank Lloyd Wright that is the tallest building he ever blueprinted. Across the street stands the impressive forumlike Community Center, designed by a Lloyd Wright protégé. The town even brags that its acoustics are world-renowned.

You want culture in the Osage Hills area? Forget near-by Tulsa; Bartlesville boasts a symphony orchestra, a civic ballet, choral society, art association and theatre guild.

U.S. 60 led me westward along the scenic Osage Hills to Pawhuska, “Capital of the Osage nation.” The Osage were not among the civilized tribes; mounted dragoons from Fort Gibson were often dispatched to quell the unrest. Downtown Pawhuska is lined with faded brick facades, including its 1894 sandstone city hall. The town’s notion of high culture differs somewhat from that of Bartlesville, however. A crude billboard proudly announced next Saturday night’s mud races: “Mud flies at 7 p.m.”

Ponca City lacks any semblance of charm along its traffic-clogged, strip-malled U.S. 77 corridor. The 17-foot-high statue of a pioneer woman does draw one’s interest to the role of women in establishing settlements during the Cherokee Strip land run. Also in town is the 55-room, Italian Renaissance mansion of Oklahoma oil baron and former governor, Ernest W. Maryland.

Now I headed north into Kansas on my way to Nebraska, hopeful that state would reveal equally interesting history and personality. I certainly found Oklahoma economical. Gas prices were low, as one might expect. Museum fees were either a paltry $3 or a donation. Tent camping in state parks was a reasonable $6. Cafés didn’t gouge, but indulged. And finally, to paraphrase Will Rogers, “I never met an Oklahoman I didn’t like.” Leastwise, not on this trip.

(This article I’d Sooner Be in Oklahoma was published in the January 2000 issue of Rider magazine.)