Designated as a federal highway in 1926 and running from Chicago to Los Angeles, Route 66 connected – and often ran right through – Midwest and Southwest downtowns. It was quite literally America’s Main Street. By the 1950s, Route 66 had become an attraction in and of itself, serving as inspiration for numerous hit songs and TV shows and as a livelihood for countless small business owners.

But when the interstate system bypassed much of the old route, the heyday faded, businesses dried up, and many establishments were abandoned. Eventually, the all-American road was almost entirely chopped up and decommissioned.

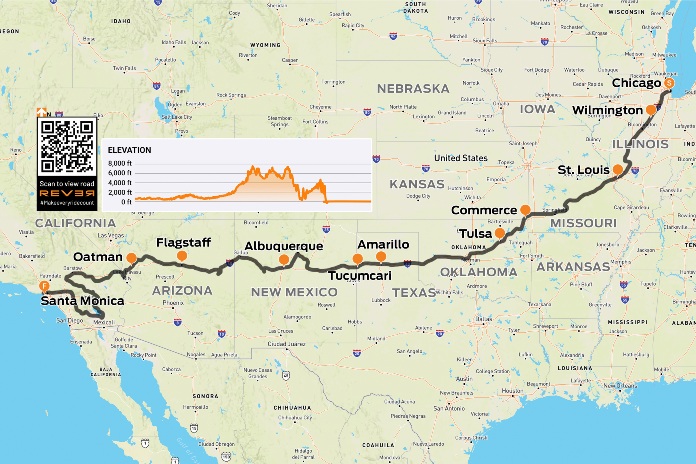

Scan QR code above or click here to view the route on REVER

The good news is that today, up to 85% of the route remains, and preservation programs are actively at work. Because it has been disconnected and signs removed, however, a ride on Historic Route 66 requires some planning. Local tourism resources can be very helpful.

The starting point of Route 66 is in downtown Chicago within sight of the former Sears Tower (now called the Willis Tower). As you ride out of the city, you’ll see the Blues Brothers dancing atop a neighborhood bar, a big red guitar attached to the Illinois Rock & Roll Museum, and the Old Joliet Prison. Soon I realized there is more to see on Route 66 than could possibly be crammed into one adventure. This is a ride, after all, not a scavenger hunt. I settled into a rhythm, and the joy of road-tripping sprang to life.

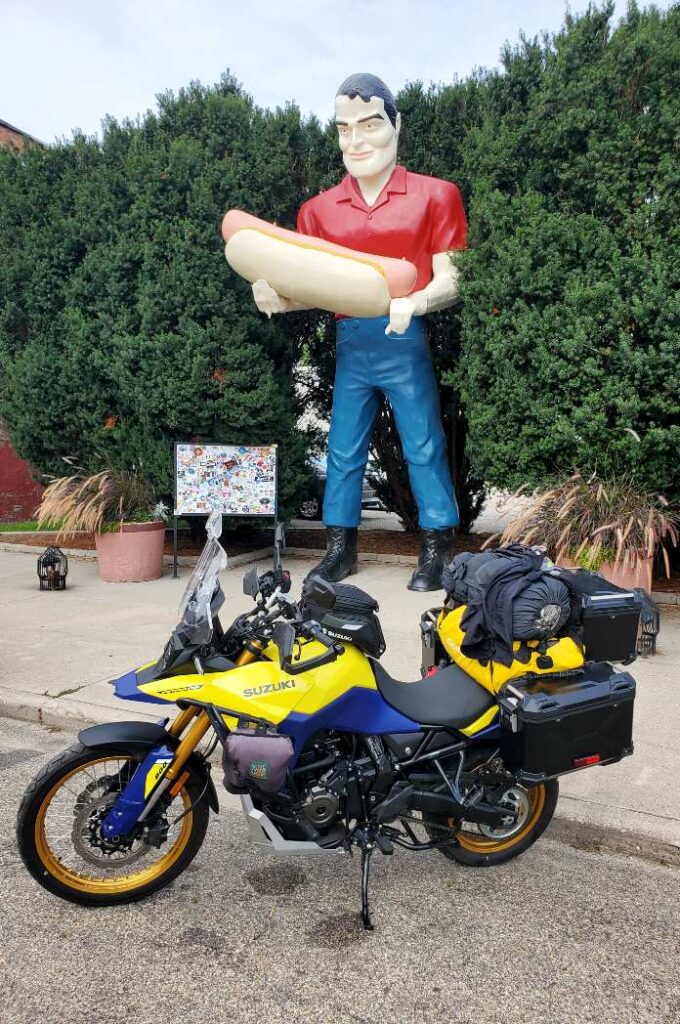

In Wilmington, Illinois, I stopped to pose in front of the Gemini Giant, one of the most iconic Route 66 roadside attractions. Across the country, I would encounter similar “Muffler Men” statues that had been variously repurposed. The Gemini Giant – a spaceman holding a rocket – once beckoned hungry travelers to the Launching Pad Drive-In; now his commanding presence graces South Island Park. Wilmington was also the first of many towns where I discovered a large Route 66 mural. All it needed to create the perfect photo was a motorcycle propped in the foreground.

In St. Louis, I was determined not to let the heat keep me from getting a photo of the Gateway Arch. But after that, I turned to the interstate for rescue. Points of interest in the downtown core just didn’t seem worth the fight, and it wasn’t until I was well out of the city that I returned to U.S. 66 and again breathed deep.

In the cool shade of Ozark oaks and chestnuts in Newburg, Missouri, I discovered a battered sign for John’s Modern Cabins standing, ironically, over three collapsing log shacks. In Sullivan, on the other hand, I pulled over in front of Shamrock Court Motel, a vacant building of stonework too beautiful to discard. Happily, it was the first of many classic buildings I would encounter where the local Route 66 association was busily engaged in restoration. Typical of early motor courts, it features a series of rooms arranged in a semicircle around a central courtyard.

A nearby barn roof bids travelers to see “Meramec Caverns, Next Exit,” and to dine at “Stuckey’s, Since 1937.” And I couldn’t resist the puerile invitation to stop at Uranus Fudge Factory for a giggle. Billboards had been full of innuendo for miles, and the fictional town of Uranus (located in the real town St. Roberts in Pulaski County, Missouri) comprised a row of confectionaries selling candy, gifts, T-shirts (don’t buy one for your mother), and of course, fudge.

From Missouri, I breezed through the southeast corner of Kansas and into Oklahoma with its sprawling cattle ranches. In the tiny town of Commerce, I stopped to pay my respects at the home of baseball legend Mickey Mantle and then explored a retired stretch of Route 66 that was only 9 feet wide. It was hard to imagine that the engineers could not foresee a day when opposing vehicles would regularly need room to pass each other. Simpler times indeed.

The route soon brought me to the Blue Whale of Catoosa. Built in the early 1970s on the edge of a pond, the large concrete whale attracted swimmers who would fling themselves off its tail or slide down its fins. I discovered the water was murky and swimming was no longer permitted, but the whimsical whale continued to draw pop history buffs.

In many small towns, I encountered retro fuel stations, museums, diners, and “The World’s Largest [Gas Pump/Rocking Chair/Cross of Our Lord/Branding Iron],” each continuing the tradition of vying for travelers’ attention. In Amarillo, The Big Texan Steak Ranch still issues its famous challenge: “If you can eat our 72-ounce steak in under an hour, it’s free.” For me, 4.5 lb of meat was out of the question, but I left the restaurant with a full and happy belly en route to the famed Cadillac Ranch, where a row of spraypainted cars are buried nosedown in an Amarillo cow pasture. Legend has it that the infamous site was born from the misadventures of a man who drank too much whiskey, lost big at poker, and had to bury his beloved collection.

Aiming for Tucumcari, New Mexico, I watched as the tawny bunchgrass turned to stunted creosote bushes, and the distant mesas crept ever closer. In the mellow light of late afternoon, I rolled up to the Blue Swallow Motel with its pink and blue neon sign, a classic Buick parked in front, and a garage attached to every room. This is one of the best-known and most authentic accommodations on Route 66, and I enjoyed a quiet evening with other travelers, all of us sitting outside in the courtyard under the neon and starlight.

The next morning at the Blue Hole, a small lake in Santa Rosa, the sapphire water was so still and clear that I wondered if I could see the bottom, but 82 feet is a long way down. The hole is deeper than it is wide (60 feet), and it’s fed by an underground spring that keeps the temperature at a constant 62 degrees. I watched as three divers in wetsuits completed their scuba training. And soon an intrepid mom with her three teenaged boys cajoled each other into jumping off the rocky ledge. They came up shouting – and then did it again.

Across the limitless stretches of Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico, Route 66 often disappeared – either abandoned on the open range or laid to rest under sprawling I-40. Posted speed limits were often 75 mph, and keeping up with the flow meant pushing my Suzuki V-Strom, nicknamed Suzette, to 85. Finding the two-lane Mother Road again was always a happy moment: Not only was it the focus of my trip, but the headlong traffic disappeared, and I had the forgotten road to myself.

In Albuquerque, while searching for a place to wild camp in the gathering dusk, the ride up into the mountains caught my breath. Below me lay the city, its streetlights twinkling along the valley, and a full moon was just clearing the distant peaks.

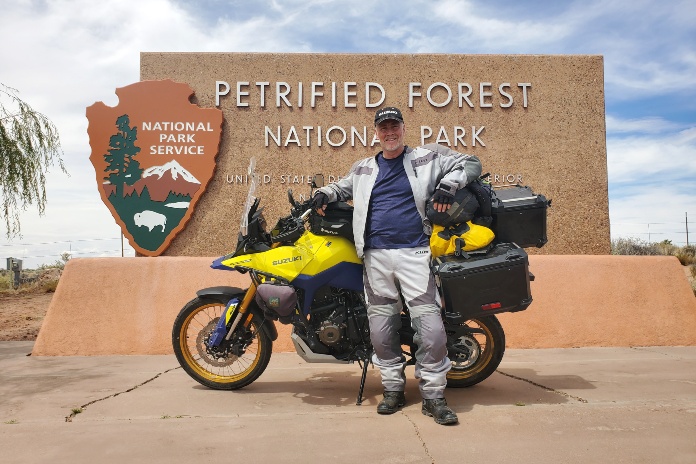

The next day, scattered ocotillo and saltbush signaled my entrance to Arizona, where I made a detour through Petrified Forest National Park. Approaching Winslow, a voice in my helmet began leading the Eagles in a continuous loop of “Take It Easy.” It is state law, of course, that when in Winslow, Arizona, you must stop to stand on the corner where a bronze statue of Glenn Frey awaits the girl in the flatbed Ford. A red one just happens to be parked at the curb.

Rolling into Flagstaff brought an entirely new landscape: Soaring ponderosa pines filled the city with their perfect shapes like an army of jubilant Christmas trees. As I rode through deep forests to the west, their vanilla scent wafted on the breeze – which was a refreshing 70 degrees. I should not have been surprised by the temperature, given that Flagstaff sits 6,800 feet above sea level. Just west of town, I-40 crosses the Arizona Divide at 7,335 feet – the highest elevation on all of Route 66.

As I inched ever closer to the Mojave Desert, the daily extremes became more pronounced. Days continued to broil, but the nights were beginning to call for my Sea-to-Summit sleeping bag liner. Beyond Peach Springs, the chip-sealed route was narrow and bordered on both shoulders with long berms of dirt – a feeble defense against torrential monsoon rains that can trigger flash flooding. Rather obviously, signs located at every dip warned “DO NOT ENTER WHEN FLOODED.” Or perhaps it wasn’t so obvious: I was amused to learn of Arizona’s “Idiot Law,” which specifies that if you enter a flooded road and get stuck, the authorities will not help – rescue and the associated expenses are on you.

Route 66 soon began a long series of twists and switchbacks as it rose into the Black Mountains. With no guardrails, no shoulders, and loose gravel in the corners, it was a demanding ride. Perhaps in a nod to the Tail of the Dragon, a roadside sign claimed there were 191 curves in 8 miles, but on this route, no one was racing.

I arrived in the Wild West ghost town of Oatman on a Sunday afternoon of a long weekend, meaning tourists were in full attendance. The main street was even temporarily closed for a gunfight – I saw two men fall with my own eyes. The biggest attraction, of course, is the wild burros. Oatman was a turn-of-the-century gold-mining town using hundreds of burros to haul ore and supplies, but when the boom went bust and the population moved on, the animals were simply turned loose to graze in the mountains. Their descendants still wander the hills around the town – and frequent the streets where delighted visitors offer free handouts.

Crossing into California, I made a loop through Joshua Tree National Park and swung south on a detour that would take me down (quite literally to 200 feet below sea level) around the Salton Sea to Slab City and Salvation Mountain. The result of one man’s lifelong religious devotion, Salvation Mountain is a 50-foot-tall monument of adobe and bright paint proclaiming “God Is Love.” Next door stands Slab City, an abandoned army base where vagrants and off-the-grid dwellers have moved in and claimed it as “The Last Free Place in America.” And of course, in the desert around Borrego Springs, I had to snap photos of the iron sculptures of horses, camels, elephants, scorpions, and a great mythical dragon that appears to swim through the sand (and under the road).

My return to Route 66 meant braving the sprawl of L.A. – a daunting prospect if not for lane-splitting, that most blessed California concession. I wandered the city and got photos of the iconic Hollywood sign and of course, the Walk of Fame. Dinner was at a staple of Route 66: Irv’s Burgers, where the walls are adorned with photos of celebrity guests, including David Lee Roth (with bikini-clad twins), the Wayne and Garth characters of Wayne’s World (played by actors Mike Myers and Dana Carvey), Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, Jeff Bridges, and Linda Ronstadt.

Arriving bright and early the next morning at the Santa Monica Pier, I expected I’d have to walk the final quarter mile to a sign reading “66: End of the Trail.” Instead, a security guard at the pier’s entrance looked me up and down and then glanced left and right.

“It’s early,” he said. “No one’s here; go ahead.”

And so after 2,448 miles through farmland and forests, mountains and deserts, I posed for photos with Suzette at the end of the road – at the very end of the pier. We’d done it! Strangers sensed a celebration and gathered around. Some wanted to talk. Others offered fist bumps and handshakes. Common to all was a kind of nostalgic admiration for our achievement – a reverence that could only be stirred by the myth of America’s Mother Road.

Route 66 Resources

- Route 66

- Chicago Tourism

- Illinois Tourism

- Heritage Corridor

- Great Rivers and Routes

- Missouri Tourism

- Gateway Arch

- Pulaski County, Missouri

- Oklahoma Tourism

- Texas Tourism

- New Mexico Tourism

- Arizona Tourism

- California Tourism

Read More about Route 66:

Yore Mother Road: Recollections of a Route 66 Motorcycle Ride

Get Your Kickstarts on Route 66

Flagstaff to Barstow on Historic Route 66

Route 66 Motorcycle Ride in Oklahoma

Arizona Route 66 Motorcycle Ride

See all of Rider’s touring stories here