C. Jane Taylor’s moto memoir Spirit Traffic was published in 2022. That summer, she and her husband embarked on a 97‑day cross‑country book tour on their BMW F 650s. She said her book tour was characterized by deeply rewarding and completely exhausting work. It also featured great roads. During her vacation from what some might already consider a vacation, she enjoyed many memorable rides. The leg from Gunnison, Colorado, to Hovenweep National Monument in Utah was a favorite. –Ed.

West of Gunnison, Colorodo, U.S. Route 50 was closed. We’d seen signs about the closure for at least 100 miles. Those signs were for other people, right? We’d planned to stay on the famous Colorado byway through the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests as long as we could. But as we approached Gunnison, our shoulders slumped with the reality that the signs were for us. We’d have to rethink our whole route. And the weather was starting to look iffy.

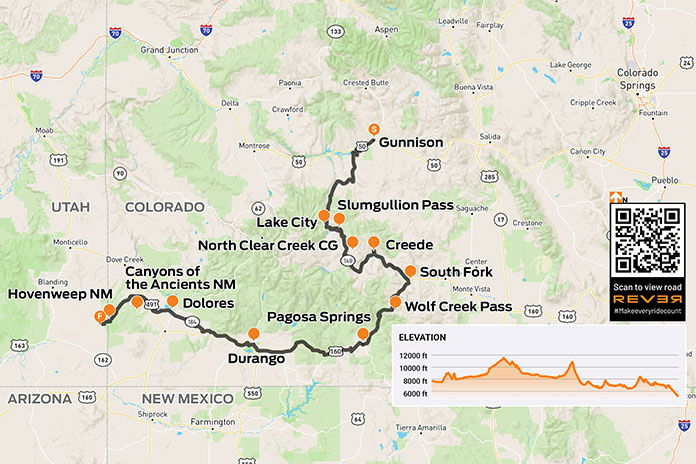

Scan QR code above or click here to view the route on REVER

At the Gunnison County Chamber of Commerce, a note taped to the door underscored the closure. We went inside, paper roadmap in hand. At the desk, the clerk proffered her own map, opening it in front of us. She and John pored over it like kids seeking clues to lost treasure.

She confirmed that U.S. 50 was closed and suggested State Route 149 instead. It had less traffic and was more beautiful, she assured us. We compared her map to the Butler map for the region. (Butler Motorcycle Maps highlight the best roads, rating them on twisties, traffic, road surface, etc.) SR‑149 was G1 (gold), Butler’s highest rating – perfect!

After filling our water bottles, we headed to the gas station. SR‑149 is quite rural, so we wanted to be prepared. As John filled our tanks and I surveyed the darkening skies, a bolt of lightning ripped through the clouds. Thunder crackled. A guy next to us gassing up his pickup was watching too.

“Hope you’re not going that way,” he said, nodding toward the storm.

“Not anymore,” I said.

We paid for our gas as the storm clouds gathered closer and closer. Thunder rumbled, and lightning struck from cloud to ground in the near distance. We sped back to the park next to the Chamber and ran for the cover of a gazebo. Just as we stepped under, buckets of rain dumped from the sky, and lightning dashed all around us. The thunder was so loud that we ducked our heads each time it clapped.

Celebrating our excellent timing, we stretched out to nap on top of the picnic tables just as two vans arrived and disgorged two dozen kids. It was the local mountain‑biking camp escaping the weather. We were instantly surrounded by kids eating popsicles and playing a raucous game of tag. Now each thunderclap was accompanied by the ear‑piercing screams of prepubescent mountain bikers. One of the camp counselors checked in on our welfare, asked about the bikes, and offered popsicles, which we accepted.

The lightning eventually abated, though the rain drizzled on. The camp counselors packed their charges and drove away. We wrestled into rainsuits and got back on the road.

Related: C. Jane Taylor | Ep. 45 Rider Magazine Insider Podcast

SR‑149 was as wonderful as described: a narrow, almost abandoned two‑lane road snaking seductively through the San Juan Mountains and the Rio Grande National Forest. The weather was cold and drizzling, but the road was curvy, and the air smelled like earth and springtime in New England. We were in motorcycle heaven.

Ten miles down the road, oncoming cars flashed their headlights, gesturing to slow down. Thinking they were trying to warn us about a cop, I laughed. It had taken me five years to get up to the speed limit. We continued with caution until a mudslide stopped us in our tracks. If we hadn’t been wearing helmets, we would have scratched our heads in a “Now what?” gesture. Like U.S. 50, it seemed SR‑149 would soon be closed too, but we gingerly traversed the shallow edge of the slide at the far‑left side of the road. Alert to the changes in road surface and rambunctious streams in the gullies flanking the road, we pushed forward like children anticipating candy at Halloween.

Instead of candy, we sought groceries as we rolled into Lake City and its tiny country store whose proprietors seemed to be a badly mismatched couple. The woman in long braids glared at us as if we’d tracked mud onto her freshly mopped floor, while the man – handsome in a Willie Nelson kind of way, if Willie Nelson could be considered handsome – happily greeted us, teasing about our florescent green rainsuits. “We are not men, we are Devo,” he joked in a robotic voice referencing the ’70s New Wave band famous for their quirky spaceman costumes. We bought vegetables, tortillas, and cheese for quesadillas we would cook once we found a campsite for the night.

Lake City is an eye‑blink of an old mining town with the down‑at‑heel aspect of a climate-change ski resort in shoulder season. The cold, damp weather did not bring any charm to the Grizzly Adams cabins lining the road.

I attributed the town’s creepiness to its horror‑movie sepia tones and bad weather, but I later learned that Lake City gained notoriety in 1875 when Alferd Packer, the “Colorado Cannibal,” was charged with killing and eating the prospectors he’d been hired to guide through the San Juan Mountains after the group had become snowbound. In the spring, five bodies with human teeth marks were found at the foot of Slumgullion Pass. Lake City’s Hinsdale County Museum has an extensive collection of Packer memorabilia, including a skull fragment from one of his victims and several buttons from the clothes of the five men he ate. The area where the bodies were discovered is now known as Cannibal Plateau. Odder still, the area hosts an annual Alferd Packer Jeep Tour and Barbecue.

My unease was supplanted by the fear and exhilaration of climbing out of town along steep, wet switchbacks to Windy Point Observation Site and Slumgullion Pass. As we climbed, I chimed into the headset, “Don’t look right, Johnny.” The narrow two‑lane highway had no guardrail, and the drop-off induced a vertigo that made me tighten my grip on my handlebar and tank. At Windy Point, we stopped to look back at the long narrow valley thousands of feet below us.

Evening was approaching, and we were still in the middle of a sheer climb on our way to North Clear Creek Campground, a destination we were not sure even existed, but the sky finally opened, and the tight switchbacks loosened as we topped 11,530‑foot Slumgullion Pass.

The map we consulted – and re‑consulted – showed the campground within 50 miles. Trying to keep from being swept up in the National Geographic beauty of the broadening landscape, I kept my eyes peeled for a Forest Service campground sign. We were hungry and cold, and it was getting late. We’d passed so little traffic, I was game to pitch the tent at the side of the road, but John persisted.

We finally turned off SR‑149 and crossed a cattle guard onto Forest Road 510, which fell away to vertiginous Class‑IV switchbacks. I groaned but also laughed. It was the “dropping hour.” We have a joke that on extended motorcycle trips, we often face the most challenging miles of the day right before arriving at our destination exhausted and hungry. The road toyed with us. I inched down its sharp gravel turns, determined but cautious given the hour. As I eased down one hill, a young woman on a dirtbike blasted up it. Encouraged that there might be an actual campground ahead and inspired by another woman on a bike, I sped all the way up to 2nd gear!

After almost missing the 70‑degree turn into the campground at the bottom of the hill and duck‑walking the bikes back over sandy gravel ruts, we casually rolled into the nearly vacant campground and found a suitable spot with a picnic table, breathtaking panoramic views, and a glorious sunset reflected off the peaks of the Rio Grande National Forest.

The next morning was cold and clear. With visions of coffee and pastries dancing in our helmets, we headed toward Creede, home to an underground mining museum, the Mineral County Landfill, a cemetery, a chapel, and an excellent little food truck/coffee shop that appeared to be set up during the pandemic like a one‑way street, with one entrance and one exit. The pastry case was filled with buttery French confections, the air with the scent of espresso. Bon appétit! We took our pastries to a table outside where we lounged, sipping cappuccinos in the sun.

The road along the Rio Grande – which far downstream serves as the border between Texas and Mexico – was as good as the croissants. At South Fork, we headed south on U.S. Route 160 and climbed to 10,856‑foot Wolf Creek Pass. It was cold at elevation, and we encountered traffic and threatening weather, but the road was smooth, wide, and curvy through Pagosa Springs and Chimney Rock. We lunched in Durango after a torrential downpour trapped us under a busy highway underpass.

U.S. 160 through the mountains near Hesperus Ski Area was fabulous despite the cold and wet. Things got warmer as we descended out of the mountains, and by the time we got to Mancos, we were sweltering in the heat of the desert. We took off as much as we could and poured cold water down the backs of our armored jackets. Body temperature management was a challenge we had improved at over time.

In the blazing heat, we headed west on State Route 184 toward Dolores, then north on U.S. Route 491 past Yellow Jacket and into Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, administered by the Bureau of Land Management and inhabited almost solely by spirits. The road narrowed and then narrowed again. There is something gritty and fundamental about these small roads, something secret and unspoken like the second indents of an outline of one’s life or the dark side of the moon.

The heat kept building. As we crossed into Utah, the landscape gave way to a barren, flat emptiness without trees or buildings. We traveled in silent awe, feeling exposed in the heat but excited about the ruins of Hovenweep National Monument.

Known for six groups of Ancestral Puebloan villages, Hovenweep contains evidence of occupation by hunter‑gatherers from 8,000 B.C. until AD 200. We were finally going to visit the spirits we’d been sensing on this hot road.

We turned into what seemed the middle of nowhere, but John assured me this was the way. I saw only shrubs, grasses, and sage until I glimpsed a sign the size of a sheet of paper with an arrow proving him right: Hovenweep National Monument. We traversed a lunar landscape of sand, craters, dead volcanoes, and lava flows until we happened upon a herd of wild horses in the middle of the road. We stopped to gape. Shy and beautiful, they paused in their grazing to examine us. Though I wanted to join these beasts on a romanticized journey out of a dream, we had to keep moving. Standing still in the late afternoon heat was a torture neither of us wanted to endure – magical, wild horses notwithstanding.

Reminiscent of Death Valley with its lethal sun, long straightaways, and distant bluffs, Hovenweep Road also reminded me of the song by America “A Horse with No Name.” I started to understand the line “In the desert, you can’t remember your name.” In the heat and arid sameness of the landscape, time seemed to stop. I could tell we were moving, if only for the visual cue of the scenery receding in my mirror. I became flooded with the eerie sensation of being watched. It felt as if the ghosts of millennia were hovering just above the heat waves upwelling from the macadam.

“Hovenweep” is a Paiute/Ute word meaning “deserted valley.” As we rode into the scorched campground, I sensed that the ancestors were still there. A clan of attentive ravens seemed to be protectors – or just eager to see what food they could liberate from us.

After pouring rationed water onto our heads and down our backs, we hiked off to see the ruins, following a faint path between rock walls leading to a dry creek bed. Walking fast to beat the setting sun, we climbed down into the creek bed then up the other side until we saw what looked like a crumbling brick silo. Hovenweep at last! As we gazed in silence at the majestic ruins of a once‑lively community, a rainbow broke through distant storm clouds. Back at our campsite, we cooked dinner in the waning light as a million stars began to wink.

I’ve ridden the routes talked about in this article many times, and it’s fun and beautiful! Great article.