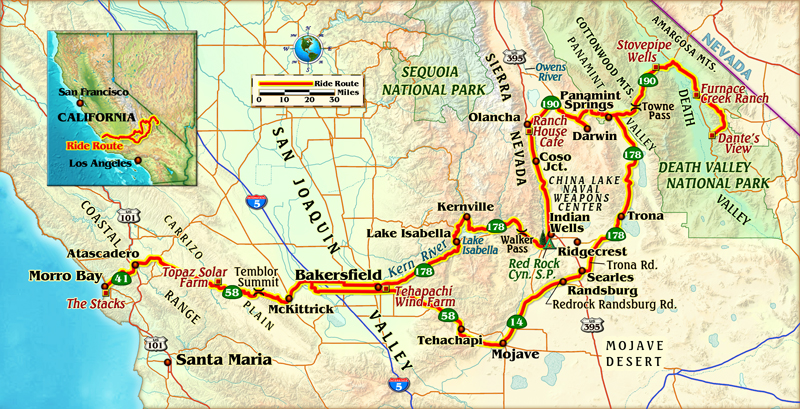

I always enjoy riding over to Morro Bay…and not just for the pleasure of calamari and chips at Giovanni’s. Coming down the west slope of the Coastal Range I see three tall towers in the distance, looking just like a cricket wicket. All they lack are the two little bails balanced between the three. For some 60 years, since the early ’50s, these 450-foot towers known as The Stacks vented the natural gas-fired powerplant. Which, for the environmentally concerned, is about as clean a fossil-fuel combustible as can be found. At full throttle the plant could generate some 650 megawatts.

Then a nuclear powerplant was built a few miles down the coast, and Morro Bay became less and less important in the matter of generating energy. It was closed in 2014, but the word was that an outfit called GWave would build a wave farm out in the ocean, wiring that energy into the old plant, since it had the all the connections needed to transmit electricity. No telling what might happen, but it would be nice to have an infinite supply of power that required no fueling system.

We rate power differently, depending on its purpose, and its generation. Wood was the original fuel, and we use it today, rated in British Thermal Units. What’s a BTU? The amount of energy it takes to heat one pound of water one degree Fahrenheit. Steam engines used wood, until engineers understood the increased efficiency of coal. The first motorized two-wheeler was Sylvester Roper’s coal-fired steam-powered velocipede in 1868. Unfortunately the warm-up time was a bit much.

This brand new Indian I’m riding uses a more up-to-date source of power, gasoline. The fuel-injected Thunder Stroke 111ci (1,811cc) V-twin engine puts out about 75 horsepower at 4,100 rpm. And the noteworthy part is really the 109 lb-ft of torque coming on at a modest 2,400 rpm. Crack that throttle and your arms get longer!

Read our full Road Test Review on the Roadmaster Classic here.

I’m headed out to Death Valley on the Indian to meet a couple dozen friends for our annual gathering, going on since 1977. On my 900-pound mount, with its 65-inch wheelbase, I don’t think I’ll be chasing anyone through Titus Canyon, but the bike is great on the open road.

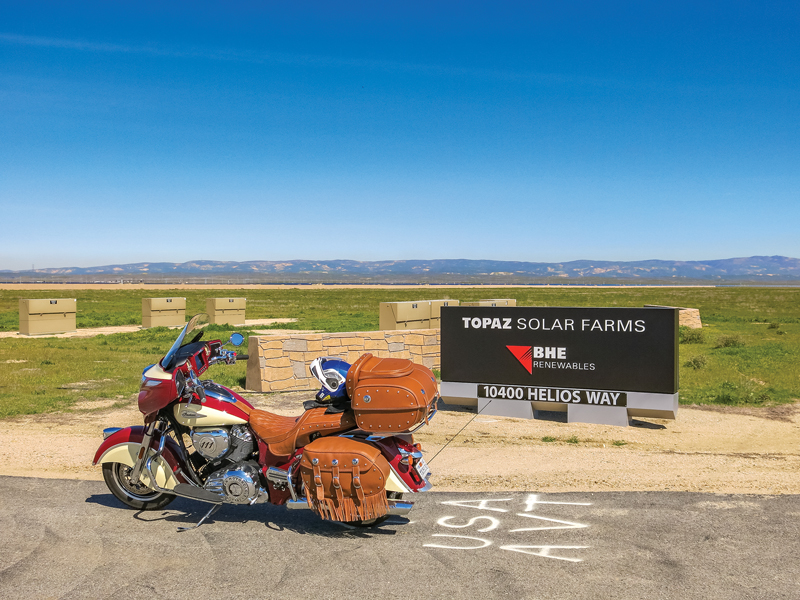

I’ve done the trip over from Atascadero many times, and this one will be a little different, as I have decided to stop and have a quick gander at all the powerplants along the way. Fifty miles east of my home lies the Carrizo Plain, with Topaz Solar Farms, one of the largest solar power generating facilities on the planet, its 9 million photovoltaic panels putting 550 megawatts online. That is pretty clean energy, sucking up the sun’s power during the day, presuming it is not cloudy. What Topaz generates during the day needs to be used during the day…because we don’t yet have the technology to store all this electricity. The average American household does require a lot of energy in daylight hours, like refrigerators and computers, but we also need to see what we’re doing after dark.

It should be noted that Polaris, the parent company of Indian, is also working on building an electric motorcycle that can go farther than any current battery-powered bike. Electric motorcycles are great, but their range is limited, and recharging takes time. I can fill up the Indian’s 5.5-gallon tank in a couple of minutes, and I’m good for another 150-160 miles—I could probably hit 200, but I tend to develop a slight nervousness after the low-fuel warning light comes on.

Over the Temblor Range summit at 3,750 feet and down through five miles of tight curves and a couple of hairpins. I am impressed at the ability of the Roadmaster to go around these bends…a gentle scrape of the sidestand is the only touchdown. At the bottom are the McKittrick oil fields, pumping fossil fuel out of the ground for more than 120 years—and getting rather worn out. More than a thousand wells are on this field, and after extracting upwards of 300 million barrels of oil, there ain’t much left. Solar steam generators are now being used to get the heavier crude out of the ground, an interesting combination of energies. Curiously, a natural gas-powered plant in McKittrick, called La Paloma and rated at roughly 1,000 megawatts, went online in 2003 but filed for bankruptcy last year, saying there was too much renewable energy power in the state.

I cross the again-fertile San Joaquin Valley, thanks to much needed rain, and head into the Sierra Nevada, riding up alongside the Kern River on State Route 178. After five droughtish years this spring the river is a delightful torrent. Much needed. I pass the rather elderly SoCal Edison hydroelectric powerplant, which was put into use in 1921! One of the first providers of electricity in the state, it is still generating quite a few kilowatts.

The river used to be free flowing, but back in the 1950s the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was told to build a dam and create Lake Isabella, an 11,000-acre reservoir that supplies water to the ever-expanding city of Bakersfield. The lake was down about 80 percent last year, but the rains this past winter have filled it back up to about two-thirds. Looks a lot better.

I spend a night at the north end of the lake, in Kernville, with a few of the gang, and in the morning we head east, going over Walker Pass at 5,282 feet and then dropping down into Indian Wells Valley. Head north on State Route 14, and after seven miles it merges with U.S. Route 395. At Pearsonville I stop to say hello to my 25-foot blonde girlfriend, the Uniroyal Gal. She is an impressive sight, waving to all those who pass by. She’s in late middle-age now, but keeps up her good looks.

At Coso Junction, a few miles north, is a rest stop, gas station and the Coso Operating Company. What does Coso operate? Ten miles east, inside the grounds of the China Lake Naval Weapons Center, where aircraft drop lots of bombs, is the Coso Volcanic Field and Coso Geothermal, which turns volcanic steam into salable power via turbine generators putting out 270 megawatts. That started 30 years ago. Few of us spend much time thinking about the center of the earth having a fiery core that creates volcanic activity. I asked if I could ride out and have a looksee, and a very civil gent said it was entirely possible if I got a permit from headquarters in Los Angeles. Next time.

Five miles up U.S. 395 from Coso is the Haiwee Hydro Powerplant, a small plant built in 1927 on the Los Angeles Aqueduct—the remnants of the Owens River. It’s 90 years old but still capable of putting out 5.6 megawatts. After the Aqueduct was finished in 1913, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power constructed a dozen powerplants along the line.

A stop in Olancha at the Ranch House Cafe for lunch, and then we go dead straight on State Route 190 across the southeast section of mostly dry Owens Lake for 15 miles—and the Indian cheerfully revs into triple digits on the speedometer; that’s truly a honkin’ engine. The 100-square-mile lake was drained in 1926 to provide water for the increasingly thirsty city of Los Angeles, and is now the biggest source of dust pollution in the United States. However, last winter’s snowfall in the mountains has put a good bit of water back in.

Half a dozen of us take a detour to Darwin, a semi-ghost town that still houses a few people. In the 1870s miners found enough silver and lead to make a profitable living, and people were working at 20 mines and two smelters. Eventually the profitability vanished and most people left. Following World War II the place acquired its ghostly status, but a few years later electricity lines were run to town, thanks to the Rural Electrification Act, making it pleasantly habitable for the current two or three dozen inhabitants who like

the solitary life.

We return to State Route 190 and drop down 3,000 feet, on delightfully curvy asphalt, to Panamint Springs, which has ground water. The Indian’s single rear shock absorber is cheerfully old-fashioned but functional, as a small hand air pump is supplied to increase preload; it has 4.5 inches of travel. The front fork is not adjustable, but the 46mm tubes offer 4.7 inches of travel in their sliders. Triple discs do a good job stopping the minor behemoth; ABS is standard.

An hour’s break at the springs, then across Panamint Valley, climb the Cottonwood Mountains, over Towne Pass at 4,956 feet, and down to the valley of death. Soon we are rolling along past the sign showing we are 100 feet below sea level, and on to Furnace Creek Ranch. The word creek indicates water, and several springs in the Amaragosa Mountains bring water to the ranch, keeping two swimming pools full and an 18-hole golf course watered. In 1929, a small hydroelectric system was built at nearby Travertine Springs, but has long been dismantled. Now two-thirds of the power comes from SoCal Edison wires, while in the middle of the ranch a one-megawatt, five-acre solar farm provides the rest. Why they had to cut down a hundred or more palm trees to put in the panels, when they could just as easily have stuck the panels out in the desert a few hundred yards away, is a mystery to me.

A couple of days and nights of minor debauchery and the crowd splits up. I head off with two others to go back over Towne Pass and then south along State Route 178 through the Panamint Valley and on to Trona. Named for the mineral trona, which has a bunch of usefulness. At Mojave we split, me going west, the other two heading south of Los Angeles. I head up along Oak Creek Road through the Tehachapi wind farm, with some 5,000 windmills generating more than 700 megawatts of energy. And the wind does blow day and night. Not sure any birds in the area have good longevity. The sight of all these mills is unusual, and not very attractive.

I take State Route 58 over the Tehachapi Pass at 3,970 feet, and then a smooth run the 150 miles back to Atascadero. In total I’ve put 1,500 miles on the odometer, averaging 35.6 mpg. Not bad for a 900-pound bike carrying 250 pounds of rider and gear. I wonder how many more years the gasoline-powered internal combustion engine will be around?