Eleven years ago today I woke up in a church wondering what the hell happened. The wooden, one-room tabernacle, located on a quiet residential street in St. Martinville, Louisiana, used to belong to the Presbyterians but was abandoned when the congregation dwindled. Pableaux Johnson, a food writer friend of mine, had bought the church a few years earlier and converted it into a refuge, a second home in the heart of Cajun country, two hours away from the hustle and bustle of New Orleans. He turned the choir loft into a bedroom (complete with a fireman’s pole for making dramatic entrances) and the pulpit became a kitchen, an altar to cuisine you might say.

Eleven years ago today Hurricane Katrina made landfall in southern Louisiana and Mississippi, causing one of the greatest humanitarian disasters in U.S. history. The death toll was 1,836 and the storm caused upwards of $125 billion in damage, leaving 300,000 homes destroyed or uninhabitable. I was lucky enough to have the means and ability to evacuate New Orleans a few days before. Pableaux and his wife, who lived a few blocks down Magazine Street from us in the city, hosted my wife, me, several other couples and our small menagerie of pets at the church. In the days and hours leading up to Katrina’s impact, we nursed our anxiety with Cajun food and booze and sat glued to the TV, watching the enormous Category 5 tempest swirling toward us across the Gulf of Mexico.

Eleven years ago today the levees broke and New Orleans filled up like a giant bath tub. The city was shut down and residents who were fortunate enough to evacuate were told they couldn’t come back for weeks, maybe months. My wife and I had no choice but to drive our Ford F150, with the camper-topped bed filled with our freaked-out cats, some clothes, a few prized possessions and two 5-gallon jerry cans of gasoline, in a wide arc north and east to resettle temporarily with my mother and stepfather in St. Augustine, Florida. Driving across northern Louisiana and central Alabama, where gas stations had run dry and people had become desperate, was nerve-wracking.

New Orleans welcomed back its residents by zip code, with those living in the least damaged areas allowed to come home first. We lived in the Uptown section of the city, which is close to the Mississippi River and sits on naturally high ground. Flooding was minimal in our neighborhood, so we were able to return in October, about five weeks after the storm. We had seen the horrific footage on TV and photos in the newspaper of the misery and destruction caused by Katrina, but seeing—and smelling—it first-hand was another matter.

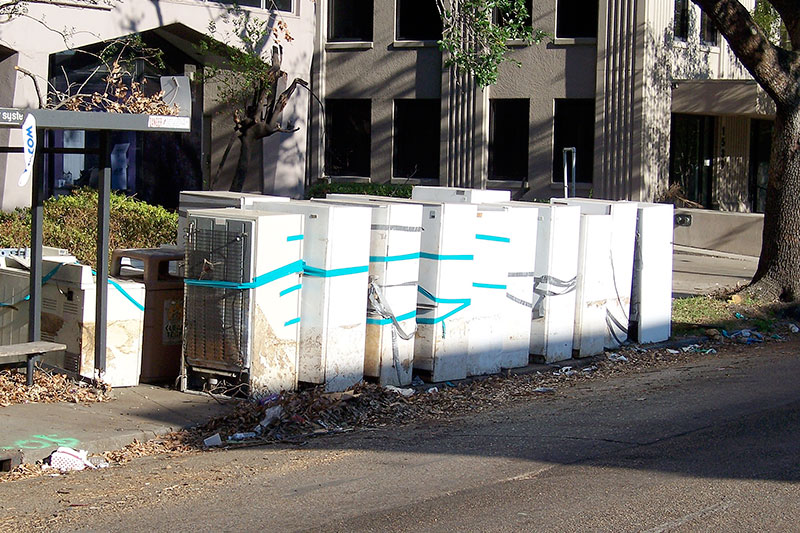

In yet another stroke of good luck, after we evacuated our landlord put plywood on all the windows of our four-unit building, which prevented them from breaking during the storm. We returned to find our second-floor apartment intact, exactly as we had left it, but with a brand-new, empty refrigerator humming away in the kitchen. (When the power went out in the city, the food in everyone’s refrigerators rotted for weeks. City streets were lined with junked refrigerators, their doors sealed shut with duct tape to keep the putrid contents from leaking out.) There were no roof leaks, no toxic mold. Even our two motorcycles, which we had left chained to a pole behind our building, were unharmed. The only evidence of neglect were long, green vines that had slithered around the wheels and up inside the bodywork.

We were lucky indeed. Having evacuated to St. Martinville and then St. Augustine, those patron saints must have been looking out for us.

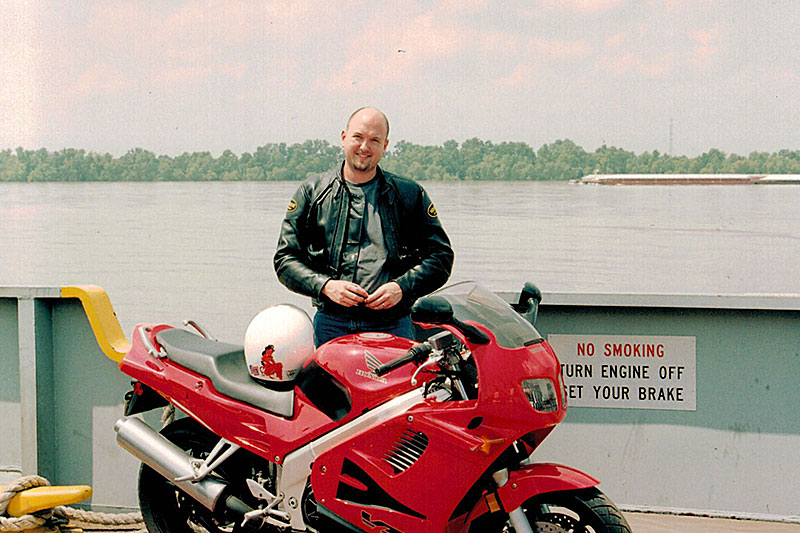

When my wife and I moved from Philadelphia to New Orleans in 2003, we brought our motorcycles with us—my Honda VFR750 and her Suzuki Bandit 600. We moved to New Orleans on a whim, to get away from the cold of the Northeast and to embrace the funkiness of the Crescent City. We savored its food, its music, its people, its architecture and its institutionalized leisure (second-line parades, music festivals, Mardi Gras). We tolerated its heat, its humidity, its almost Third World-level dysfunction.

Built on the accumulated alluvial soil of the Mississippi River delta, New Orleans and the rest of southern Louisiana is built on unstable ground. Add in years of deferred maintenance and you end up with city streets that are in really rough shape. For motorcyclists, leaving the city is your best bet. Traffic is minimal and the scenery is unique—wetlands, small towns, antebellum plantations, petrochemical plants and the seemingly inescapable levee system. Except where roads follow the contours of rivers or bayous, they’re typically straight and flat.

For a variety of reasons, during my three years in New Orleans, I didn’t ride much. Not my motorcycle, at least. Sure, I rode my bicycle down to the French Quarter to go barhopping, but I didn’t escape the stress of running a small business and my crumbling marriage by exploring the back roads of Louisiana on my VFR. Maybe it was the oppressive humidity. Maybe it was the scarcity of curves. Perhaps it was just plain laziness.

Finally, a couple months before Katrina, I made my escape—a multi-day solo tour up into Mississippi, riding the length of the Natchez Trace Parkway to Nashville, over to Knoxville for the Honda Hoot rally and to ride the Tail of the Dragon (nine times!), and then home again after exploring the North Georgia mountains. It was a restorative trip, but little did I know at the time, life was about to change.

We returned to New Orleans after Katrina and found the city turned upside down. A few months later, my marriage ended up on the trash heap like a taped-up refrigerator. Alone and confused, I did some soul-searching on my motorcycle. I rode southeast, through the Lower Ninth Ward, which was hit hardest after the levees broke, and into St. Bernard Parish. Continuing south on State Route 39, I followed the eastern edge of the Mississippi River, down into Plaquemines Parish. Located east of New Orleans on the Mississippi’s porous alluvial fan, St. Bernard and Plaquemines were steamrolled by Katrina. Destruction was everywhere and, even months after the storm, very few residents had returned home, or had homes to return to. I parked my VFR atop the levee and sat watching the river barges cruise by, contemplating the unexpected twists and turns life takes.

Hurricane Katrina displaced a lot of people, some voluntarily, some involuntarily, forcing many to forge new paths in their lives. In the spring of 2006, about eight months after Hurricane Katrina, I pulled the rip cord. With no family roots in New Orleans, and not keen on the prospect of living in a city with a smaller footprint and regularly bumping into my ex-wife in our favorite water holes and living rooms, I took a job in Los Angeles. Two years after that, I got hired as a staffer at Rider magazine. So, in a weird sense, if not for Katrina, which hastened the dissolution of my marriage and motivated me to move to California, I would not be where I am today.

Like most people who’ve lived in New Orleans, the city got into my blood and will always be a part of me. I went back in 2007 for Mardi Gras, and again in 2009 for the Triumph Bonneville press launch, where I befriended Maxwell and Zachary Materne, two brothers whose family owns The Transportation Revolution (TTRNO), a large European motorcycle dealership in downtown New Orleans, one of the many businesses that were a vital part of the city’s restoration. TTRNO also runs the Motorbike Speed Shop, a trackside garage at the NOLA Motorsports Park, a road course located across the river from New Orleans that opened in 2011. And Maxwell collaborated with JT Nesbitt—the former Confederate Motorcycles designer best known for the Wraith—on the Magnolia Special, a compressed natural gas-powered car. (When Confederate relocated from New Orleans to Birmingham, Alabama, after Katrina, Nesbitt stayed put and established Bienville Studios.)

My buddy Pableaux, who was born and raised in Louisiana, is still there. Known for his open-door policy of serving red beans and rice at his home on Monday nights, he now takes his comfort food on tour with his Red Beans Road Show.

Katrina left some pretty deep scars, but the people of New Orleans and southern Louisiana are resilient and have come back stronger. Creative, energetic people like the Materne brothers, JT Nesbitt and Pableaux Johnson, along with thousands of musicians, artists, chefs, dreamers and everyday folks, make the Big Easy the one-of-a-kind place that it is.

Wintwr of 2015 I rode solo from PEI, Canada – isolated parts of Mexico – El Salvador. On my return ride to PEI I made a stop in NOLA for a few days, my first time and the first city I’d stayed in for months. I fell in love with the place, warts and all. Like the V-Strom I was riding, look at it from a certain angle and it’s got a face only a mother could love. Look at what it does, and could do? Beautiful.

I made a pledge to return with my wife; if all goes well, this winter (2017). This is a great blog with interesting links – I hope there’s more! If there’s anyone out there with “ya gotta see this” in NOLA advice, I’d love to hear it.