by James R. Petersen; photography by the author and Kevin Kane

[This Chick-fil-A Kyle Petty Charity Ride Across America Tour was originally published in the January 2007 issue of Rider magazine]

The rooftop garage corrals 175 motorcycles. I watch a man wearing an “Old Guys Rule” T-shirt wash his bike. The hotel has thoughtfully provided rags and water. Looking around I think this could be the casting call for a sequel to The World’s Fastest Indian, only this would be called The World’s Most Accessorized Ultra Classic. Nine out of 10 bikes are Harleys. I do what man has always done when confronting such splendor—I admire paint jobs, details, license plates—the personal touches. Don Wallace, owner of “FunHawg,” has a turkey buzzard devouring a rubber chicken on the back of his bike. Don Knobler doffs a helmet that appears to be the remains of a bighorn sheep, curling horns and golden mane. Can you say “Flamboyant”?

The motor marshals (nine state troopers from North Carolina) ride BMW police bikes, as do the medical team. The fuel team guys ride Harleys with sidecars in the shape of Coca Cola bottles. There are a dozen Victory cruisers, a handful of Honda Gold Wings and BMW K1200LTs, two Nortons and my Triumph Rocket III.

The oversized Dodge pickups, NASCAR trailers, vans and trucks—all emblazoned with the scorching- cycle logo for the Kyle Petty Charity Ride—would look out of place if they weren’t so polished and precise, so opulent. The noise, when the bikes start, is like paddles to the heart. As we wheel through the parking garage, theft alarms go off in unison.

When we pull out of the hotel, the kitchen staff, in white aprons and chef hats, waves. An old couple sitting in lawn chairs hold a cardboard sign: “We love you, Kyle.”

The Ride has begun.

When the phone call came I had taken out an old puzzle my children hadn’t played with in years. I had fingered the brightly colored states, pressed them into place. Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, North Carolina. I’d taken a calendar and penciled in the names of towns, and realized I was fitting whole states into 24-hour blocks. My breathing changed.

The editor of Rider had asked me to fill a seat on the 12th annual Kyle Petty Charity Ride. Triumph had kindly loaned a Rocket III. For nine days I’d be in the company of almost 200 biker-philanthropists, NASCAR zealots, supermodels, celebrities, good old boys and Southern eccentrics, all heaven bent on raising money for a good cause. He was sure I’d find something to write about. It would be classic fly-on-the-wall journalism, or, at this speed, bug-on-the-windscreen journalism.

The back story: In 1994, NASCAR driver Kyle Petty and a bunch of friends decided—pretty much on the spur of the moment —to ride motorcycles from North Carolina to a race in Phoenix, Arizona. Along the way, they called friends. Like the scene in those John Ford westerns, the posse grew along the way.

They’d pull into gas stations and the owners would lock the doors.

Then they decided to do it again, only this time for charity. Some 41,000 miles later, the ride has raised some $9 million for good causes. Since 2004, the ride has contributed to the Victory Junction Gang Camp—a summer camp for kids suffering from acute medical conditions.

What did you do on your summer vacation?

The ride is a creature three miles long. Total engine displacement is around 254,674cc, with approximately 11,405 horsepower transmitted to the rear wheels of 175 bikes. A gas stop swallows $1,500 worth of premium in a single gulp. Fuel stops are a thing of beauty, choreographed with a precision that is priceless. The advance teams cordon off gas stations with red tape. The motor marshals, assisted by state troopers and local police, block intersections, close interstate entry ramps so that autos won’t try to merge with the line of motorcycles. We ignore red lights, ride without looking over our shoulders. Flashing lights are our friend. You find out what it is like to have a motorcycle cop wave you past, urging you to catch up with the main group, when you are already doing 90 mph.

We are a moving billboard, an event in people’s lives. In every town people stand on the roadside, digital cameras glued to their eyes or held at waist level like a compass. We pass, not in a cloud of dust, but leaving behind a molecule-thin layer of megabytes. When we crest a hill, there are bikes as far as the eye can see. Bikers who pass us going in the opposite direction give the traditional wave, then have to hold the gesture for minutes.

In the daily logs posted on the Internet, Kyle acknowledges the NASCAR moms and dads who turn out at roadside. Seeing it firsthand is startling. A father hoists his child aloft as we pass; young kids straddle ATVs by the entry to a huge ranch; rafters floating down a river wave to us. People gather outside of factories and shopping malls, park their vehicles on the sides of roads and wait for hours. The farther East we go, the more people turn out. Crossing into Illinois, there are people waving from every overpass. Every one.

At every stop Kyle and his legendary NASCAR driver father, Richard, interact with a grace unmatched by any dynasty on the planet. (Only Jay Leno has a similar touch.) They are patient, unhurried, attentive. They sign T-shirts, race programs, tiny matchbook cars in Petty blue, Victory bandanas. The fans present their credentials: some pull up with their own stock cars on trailers (slightly crushed). One man shows me a check sealed in laminate plastic—he’d written it 50 years ago for tickets to a NASCAR race in Daytona, back in the day when Kyle’s grandfather Lee Petty raced on sand. A man in a wheelchair brings a life-size cardboard cutout of The King Richard Petty, something that he’d bought eight years earlier. A woman’s license plate reads 45Fanatic, and she talks about having a whole room of her house devoted to Kyle.

Not everyone is in the loop. Near Cody the girl manning the cash register at a gas stop had no idea the ride would be passing through. She’d come to work and found that seven porta-potties had appeared in the parking lot, like crop circles. “I’m an Indy girl myself. If it had been A.J. Foyt, I would have been beside myself.”

We collect moments. At gas stops we play “Didja See?” The antelopes racing beside the road? The prairie dogs that stood at attention as we passed? The giant metal eagles, with 20-foot wingspans, the color of rust? The amusement park, the wooden scaffolding of the rollercoaster silver with age? I reflect how much you learn about the places you pass through: I spot a store devoted to saws, junk d’luxe resale shops, pawn shops, taxidermists. I gauge the economy by the number of billboards reduced to “space available” pleas, places so poor no one wastes money trying to attract business or there is no local business with money for ads. Christian billboards (“That thing about love thy neighbor? I was serious about that….” God) face-to-face with a cautionary campaign for toothless meth users (“Doing meth does not help you hook up”).

The Characters

Kyle stands in the back of a pickup truck and addresses the ride with a warm humor. He stresses safety: “The laws about double lines are the same as you learned in driver ed., unless you had driver ed. with my dad, in which case you learned squat.”

On the road Kyle and Richard act as outriders, moving alongside the convoy, acknowledging each rider.

The ride is a cast of characters well-versed in comic relief. Click Baldwin, the Harley dealer who rode on that first wild-assed ride, has brought along a folding flat guy, a life-size picture of his friend Drano. He dresses the flat Drano in the T-shirt of the day and takes pictures to show Drano what he was missing. At one gas stop he hides behind the cutout and gives fingers to passersby. If Drano ever shows up in Wyoming, he may find himself in a fight. In Asheville, Kyle tongue kisses the flat Drano’s ear.

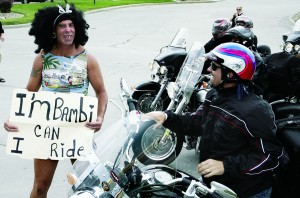

Then there’s Tommy, the cross-dressing state trooper with multiple personality disorder and scary teeth. During the safety clinic for first-time participants, he had smiled to reveal steel dentures that would make Jaws quake. Mark, the trooper running the drills, cited it as an example of “our state’s fine dental plan.” Tommy, it turns out, is a quick-change artist and master of disguise. Half the people we passed had been Tommy—the fat girl with the sign “We love him Big Fat Kim.” The guy in the superhero/Spiderman costume crouched on a picnic table. The guy pumping gas with an elephant nose. In the parking lot outside the Butte Best Western, I had noticed a figure dressed as Death or Father Time holding a sign that said enigmatically “Peace on Kyle.” It seemed vaguely threatening, and I wondered if the protester was a Jeff Gordon fan.

A few days later, as we pull into another gas stop, a tall, afro-haired transvestite hitchhiker in a tight dress holds up a sign: “I’m Bambi, Can I ride.” It’s not until I catch the glint of the Jaws teeth that I realize it is Tommy. Perhaps it indicates how long we’d been riding, but consensus is he has great legs. The routine has only gone awry once, when a trucker saw Bambi and started to pull over.

I ask Don Wallace, aka FunHawg, if he is the oldest guy in the group. He denies it and points to Bob Raiford, a personality on the John Boy and Billy Radio Network, a 78-year-old whose business card reads “Curmudgeon.” Wallace eyes supermodel Niki Taylor, who has joined the group on a Sound&Speed Triumph Rocket III. “She sure sits pretty on that bike. Prettier than you. But she’d probably sit pretty on a Cushman scooter, too.”

I discover several kindred spirits on the ride. Fred Knight, upon seeing the Rocket, warns me that I am in for a good time. He’d ridden a Triumph Rocket III through Montana on the previous year’s ride. The trick, he says, is to hang at the back of the pack. Let them get ahead, then play catch-up. The 80- to 120-mph roll-on in top gear is the ultimate grin machine. He is a natural mischief coach, and of course, absolutely correct.

On the third day of the ride, The Great Times—the morning paper that is put out for The Ride—suggests an alternate route. We can break away from the main pack to go through Yellowstone. (Knight’s great-great-grandfather, one of the original Rough Riders, had served as park superintendent in the early years, sent there by Roosevelt to curtail poaching.) I join Knight and Billie and Lisa Attaway, and head down Route 15, through huge rolling hills.

After two days of riding in a pack, with bikes as far as the eye can see, I rediscover the power of the open road. The ride is formation flying, your attention keyed to the bike in front, the regimental spacing. This is pure release, an invitation to wrap yourself in the landscape.

We enter the Gallatin National Forest in Montana. The road follows the Gallatin River through a narrow canyon, with cliffs on either side, close and intimate. I realize that the river designed the road, that I can steer the river—e.g. I can look at the winding water and choose my turning points and find them under the wheels on asphalt. It feels as though I am the shadow of the river, or the mirror, that we share a certain joy, a feeling of release. All of the clichés—feeling one with the machine, one with the road, one with the landscape—coalesce in those moments.

I have always thought of the West in terms of vastness, a huge expanse, a whole day of essentially the same thing. Wire fences. Grass. Mountains that never seem to get any closer. But the road out of Yellowstone reveals a different West: it cuts through a cleft in the rock, descends along the gorge cut by the rushing water, opens onto a wide valley with a completely different feel. We move past Mammoth Hot Springs, escape into a long green valley filled with elk and bison. The colors change from heather and sage to the white sandstone of ancient sea beds, to conifer forests, to the grays of granite or shale. There are forests scorched by fire.

When we stop for lunch at the Prospector Café in Cooke City, I allow as to how the day was shaping up to be in my top five rides of a lifetime, that in the words of a Bruce Cockburn song, some kind of ecstasy has got a hold on me.

We follow Route 296—The Chief Joseph Highway—toward Cody, and enter the secret heart of the west, a stretch of terrain that has everything: buttes, razorback mountains nuzzling at a gorge, cliffs that show the diagonal stripes of up-thrust seabeds, a freestanding cone of rock. It was like stumbling into a garage in which someone had tossed every great painting of the West. Past the Sunlight Gorge bridge, a series of switchbacks takes us through elevation changes, each revealing a new glimpse of this magical terrain. At the top, two plywood Indians point back the way we had come.

On 14A we ride past granite that is 2.5 billion years old. For the last hour, we chase a perfect rainbow. Not content, that rainbow becomes a double rainbow sending shafts of color into the hills before us. OK God, we get the point. We pull into Sheridan and look back: the sun gilds the underside of the same clouds that had created the rainbows. A cavalry band plays.

Somebody say Amen.

Near Denver, I have to break off from the group to attend to a mechanical problem. Foothills Triumph has a simple policy. “Put travelers back on the road.” In spite of a three-week waiting list for service, I receive immediate attention. By the time the repair is accomplished, I am a whole day’s ride behind the group. Sweet. The Ultimate Catch-up.

One of the unanswered questions I’d had about cross-country rides was this: How do you deal with the Great Plains, the boredom of eastern Colorado and Kansas? The answer: You ride the sky.

As I move across Route 70, two storm cells bracket the road. The one to the South seems predatory, apocalyptic, a mushroom cloud riding a stalk of rain the color of night. The cell to the North seems to keep pace: sending out thin layers of cloud—the color of oil slicks or gunmetal—that race toward the East. I am mesmerized. The clouds are the kind that Old Testament prophets used to ascend into heaven; the kind that spawn gaping-mouthed gargoyles and banshees, that argue with the earth in staggering bolts of fire.

I try to outrun the sky. Route 70 is easterly, changing direction every few miles for no apparent reason, sometimes bringing me within reach of the rain, sometimes letting me skate. A BMW passes at 100 mph-plus and I follow his lead for two hours.

Night falls and the storm cells use the cover of darkness to rearrange themselves. The entire horizon lights up, pulsing with diffuse light, nature’s own shock and awe. I pull into Salina, Kansas, at midnight. The luggage crew hands me a beer without asking.

The moments continue: A 90-year-old woman in a wheelchair giving each rider a hand-knit cross and a prayer. A young boy showing up with a T-shirt covered with name tags of riders from previous years. Having a police escort into Springfield, along streets lined with thousands of people. In Cincinnati, the city blocked off the entire street in front of the hotel to let us park. When I came down in the morning, Hershel Walker and the luggage crew had taken over the fire lane and were tossing a football back and forth.

I spend hours talking to people about bikes, about the ride, and about the reasons they had for participating. David Andreas, a banker from Minnesota says the ride is a way of “paying it forward.” (Indeed, one of the couples on the ride had won money in the Ohio lottery, and decided to pass it on to the ride.) Another rider put it succinctly: “I’ve been lucky for the past few years. The kids at Kyle’s camp have been in hell.” I get used to seeing veterans of the ride choke back tears.

I spend a few days wondering who is the heart of the ride, Kyle, Patty, Diane, the volunteers—before realizing that the ride is a single heart, 175 bikes long.

On the last morning Kenny Crosswhite, a veteran rider and preacher, gives a short sermon. He talks about the prayers we utter as we ride.

“Oh God.”

“Oh God, not rain.”

“Oh God. Lightning?”

Or what you utter in the split-second before a collision.

“Dang—this is gonna hurt.”

The shortest prayer in the Bible, says Crosswhite, is in Exodus. Moses says, simply “God, show me your glory.” The Hebrew word means weight, influence, the Old Testament equivalent of “Show me what’s under the hood.” Call it glory or influence, on this ride, He had.

And with that, we mount up and ride into the camp. I won’t describe the feeling—it is something you have to earn.

To learn more about Kyle Petty Charity Rides call (888) 45-PETTY or visit www.kylepettycharityride.com.

[From the January 2007 issue of Rider]