Wherever I journey I seek out regional motorcyclists for their advice about the best local riding. Far too often, though, I’m told by the brethren that they dash out of state, jaded I suppose, by the familiarity of their own surroundings. Such was the case when I last visited Kansas; the flatlanders I queried told me they were heading off to the hills of Arkansas or the mountains of Colorado. It wasn’t until my perspective of the state was published (Rider, August 2004) that a Kansan rider wrote to say if you want camaraderie and good riding, be in Cassoday the first Sunday of the month. I was in a contemplative frame of mind for another ride into the heartland, so I found myself heading to the Flint Hills.

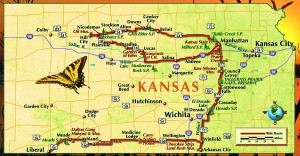

On my last excursion here I discovered that U.S. 160 across the Kansas Southern tier was a worthy scenic ride, so I sped along unencumbered by lights or traffic for 243 miles through variegated topography and geology from Liberal to Winfield, an All-American municipality of interesting parks and treasures. I rode 15 miles south of Winfield along what’s called the Walnut Valley Greenway to Arkansas City, where this territory was ceded to settlers during the Cherokee Strip Land Rush of 1893. As it happened, an encampment of reenactors was underway at the Land Rush Museum, lending an authenticity and vitality to the region’s history.

Arkansas City is the southernmost site in Kansas along the Prairie Passage, a 2,000-mile highway corridor—not yet fully developed—that will run through native wildflowers and remaining grasslands in locales from Mexico to Canada. Interpretive signs and self-guided demonstration areas inform the motorist along the way. Call (785) 537-4385 for a Prairie Passage in Kansas map or for a Tallgrass Prairie Parkway map. I am embarking on the Kansas section of the Tallgrass Prairie Parkway, U.S. Routes 77 and 177 northward.

I follow the Walnut River as it wends lazily for 65 miles to El Dorado at the edge of the Flint Hills. The town’s huge reservoir is surrounded by tallgrass prairie. This Flint Hills landscape is formed of limestone and shale deposits containing pockets of oil that became the source of growth and prosperity for Kansas in the boom days of the 1920s. El Dorado is now home to the Kansas Oil Museum, which has reconstructed a typical oil town from the era using historic buildings and full-sized oil field equipment. Geese flock to adjacent Lakeside Park, where I follow a trail alongside Walnut Creek to a waterfall beneath an iron truss fishing bridge. I find it to be a typically picturesque Kansas wayside.

It’s Sunday when I enter Cassoday, where a sign on the outskirts informs me I’m in the Prairie Chicken capital of the world. It’s a blip of a place with a population of 110 souls, founded in 1884, and lying at an elevation of 1,470 feet. I easily locate the café meeting place, but there are no motorcyclists. I saw a group back in El Dorado, despite the rain, so I’m puzzled. A sign in the window tells me that the first Sunday of the month from March to November motorcyclists gather here for a “biker buffet.” It’s September. I check my calendar. Dang! It’s the second Sunday of the month. Labor Day screwed up my plans and timing.

But I’m in luck, as the second Sunday a lunch buffet is reserved for the public-at-large. Quite a spread it is, too, of fried chicken, ham, ribs, boiled potatoes, corn, salads, you name it. There are a dozen desserts, featuring four types of cobbler, angel food cake, cream pies, mixed fruit, etc. All of this costs only $8.75, including a drink.

Besides the nourishing victuals, motorcyclists flock to the area because Cassoday is the southern terminus of the Flint Hills Scenic Byway. The road did become somewhat curvy north of town, rounding the slopes of upland prairie, passing stone fences framing emerald swatches of soybeans containing islands of limestone buildings. Rocky soils helped spare this area from the plow, except in the rich bottomland. Shale and nodules of chert, called flint, are exposed on the surface of ridges and hillsides. The surrounding bluestem pastures make for better grazing land, so the region became major cattle country. Cassoday and other nearby towns flourished as the centers of cowboy culture.

Cottonwood Falls, which I’m now passing through, became the county seat where an impressive courthouse representative of French Renaissance architecture was built in the 1870s to deal with cattle issues and rowdy cowhands. It stands as the oldest operating courthouse west of the Mississippi. Just farther along I enter Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, whose centerpiece is a Second Empire-style ranch house constructed by a cattle baron from hand-cut native limestone. A massive three-story stone barn and numerous other outbuildings complete the spread. I let the Beemer graze while I go for a look-see.

National Park rangers take visitors on a 6.5-mile bus tour of the prairie over gravel roads. The stunted grass of this upland prairie is in distinct contrast to the tall gamma grass of the Southeast Prairie Passage Loop I saw on my last visit. Nonetheless, I did learn that the prevalent Prairie Chickens find the grasslands ideal mating grounds, nesting sites and brood-bearing habitats. They must be elusive critters, because I only noticed friendly collared lizards basking on the limestone outcroppings.

Rangeland vistas open wide on the way to Council Grove. Sumac, turned paprika-red by the autumn season, appears in flavorful-looking clumps along the roadside and across the green, shag-carpeted hillocks. Limestone pillars lie like toppled tombstones amongst the oak stalks of bluestem. Interpretive wonders creep up: The ghostly silhouette of an oxen-pulled prairie schooner on a ridge to the right; a red schoolhouse to the left; my head swivels southward again to note a cattle pen; popping up on a northern ridge is a simple limestone church. This route has captured the essence of what’s called in these parts Prairyerth (an old term for heartland soils of the grasslands).

Council Grove lies on the old Santa Fe Trail, and there are no less than 14 historical sites I visit by following signposts on the self-guided tour. This is a place to stay awhile, I reckon, so I checked into the Cottage House, a restored Prairie Victorian Hotel serving travelers for more than a century. I made like a trail user out of the past and chowed down at the Hays House, itself catering to trekkers along the Santa Fe since ole Dan’l Boone’s grandson built the place in 1857. It bills itself as another “Oldest continuously operated establishment west of the Mississippi.” The Council Grove Apothecary remains a remnant of another era, offering soda fountain delights under an ornamental tin ceiling. As I peer out the window the bike appears displaced in time.

It’s early morning at the Konza Prairie overlook 30 miles north of Council Grove. Gauzy mist nestles in the Kansas River Watershed below, and sunflowers clinging to the hillsides gleam yellow radiance in dawn’s glow. While photographing myself and the bike amidst the flowering cluster with tripod and timer, an inquisitive rancher approached and heralded a snide greeting: “They don’t have sunflowers where you’re from?”

When I retorted amicably, he turned convivial. His name was Buck Ghert, indeed a local rancher who was here to meet with Kansas State University representatives who manage the Konza Preserve under the auspices of the Nature Conservancy. They were studying the impact of adding another nature trail, and Ghert was solicited to be the ranchers’ representative. The ranchers were concerned.

As Ghert explained it, much of the area is burned on a two-year rotation, resulting in native grasses that grow impressively tall so cattle can “go to grass” during the spring and summer months. Afterward, the herds are shipped to feed lots for “finishing.” Ghert and his fellow ranchers were fearful that a careless visitor might start an out-of-season burn, ruining the feed cycle. Ghert pointed out that all cattle were grass fed until about 60 years ago. But health-conscious consumers are driving the return to old-time ranching practices and grass-fed cattle.

Edified now about Prairie practices, I led the Beemer westward out of Manhattan along Highway 24, floating over ocean-swell terrain offering distant vistas of woodland-pocketed rangeland. West of U.S. 81 the road is termed a heritage route, with historic sites and attractions in every town along its length to Colby. Beloit offered the Little Red Schoolhouse at a roadside park. The location also has St. John Parish, an impressive twin-tower limestone edifice.

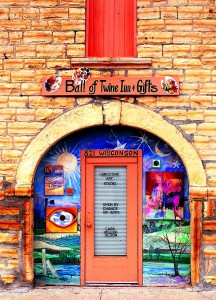

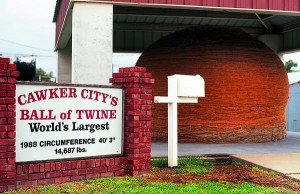

Cawker City puts itself on the map by displaying the world’s largest ball of twine. The decaying burgh tries to support itself on this quirky phenomenon alone, with gift shops and other similar storefronts. Funny how each of these Kansas villages along this route tries to imprint itself upon the consciousness. Downs is home of Kevin Saunders, world-champion wheelchair athlete. Stockton is hometown of Lorenzo Foller Jr., musical prodigy pioneer. Alton is the birthplace of Russell Stover, the candy magnate. Plainville is the boyhood home of Jerry Moran, whoever he is. Then there are the towns that inform you they are home to dated state champs in whatever sport, sometimes decades removed from their notoriety.

I chose to detach from U.S. 24 in Nicodemus, a National Historical Site noted for its African-American ancestry. Freed slaves congregated here to escape discriminating Jim Crow laws in the post-Reconstruction South. I had just missed the 128th Emancipation Homecoming Celebration, and the place seemed eerily devoid of any inhabitants.

Miles of stone fence posts appeared as I dipped southeastward over State Route 18 into the agriculturally rich Wolf Creek Valley, part of the Smoky Hills escarpment appearing as limestone bluffs to the south. Ranchers hereabouts solved their fencing problem on the treeless plains by quarrying limestone bedrock found near the surface. Freshly harvested limestone is chalky enough to be sawed, notched, drilled or shaped with hand tools. After prolonged exposure to the air, it hardens and becomes weather resistant. These Post Rocks, as they are called, have become a trademark of north-central Kansas.

Lucas is the heart of Russell County, birthplace of Senator Bob Dole. A post rock-supported limestone slab welcoming sign announces Lucas a Garden of Eden and Grassroots Art Capital. Post Rock Scenic Byway runs the 15-mile stretch between Lucas and Interstate 70. As I rode along, clouds parted after days of sporadic rain. Blessed sun and warmth! The plains seemed to rejuvenate, dancing alongside me as we both sashayed between sunspots and shadow. Rows of Post Rocks at last flashed their sun-burnished, nutmeg texture. The Byway swept beside Wilson Lake, where I looped to the top of the Smoky Hills for an unrestricted, expansive view of the countryside. Walt Whitman must have been equally inspired, for he wrote after viewing many of America’s natural wonders during his extensive travels, “…I am not so sure but that the Prairies and Plains last longer, fill the esthetic sense fuller, precede all the rest and make North America’s characteristic landscape.”

I’ve completed my second extensive loop of Kansas, some 1,100 miles. But unsatisfied and unwilling to accept the end of my tour, I scurried along I-70 for 90 miles back to Manhattan and dropped south to retrace the scenic length of State Route 177 under a warm, inviting sky. My last night in Kansas I camped at El Dorado Lake, which glimmered a mysterious moodiness intensified by a ring of barren trees resembling fanciful, grotesque marionettes.

At dusk this grove of ghostly deadwood jutting from the swampy shore looked for all the world like skeletons emerging from the underworld, transforming to splintered silhouettes against the flaring sunset. The lake and surrounding prairie seemingly fell into a melancholy sleep, drawing me into its very bosom. Before fading, I recalled to mind a Willa Cather line, which just may well aptly describe my insight into Kansas: “…The long, empty roads, sullen fires of sunset, fading, the eternal, unresponsive sky.” Actually, I found the Midwest sky very responsive, as the rain squalls, golden sunrises, ruby sunsets and dancing cloud shadows over the eternal prairie attest.

Now, to all you motorcyclists who still remain unsure about the worthiness of a trip to Kansas, I advise that there is a motorcycle museum in Marquette. It holds a Biker Breakfast on the third Saturday of the month, reason enough for another visit to the Sunflower State. See you there!

[From the November 2007 issue of Rider]

I am one person who seems to enjoy the backroads of Kansas more than most people. I especially was overwhelmed in what I saw at Monument Rocks and Jacobs Well.