When Ducati announces a new model, the world of motorcycling sits up and pays attention. In the factory in the back streets of Bologna, brilliant engineers have turned out brilliant motorcycles for decades. Back in 1973, Fabio Taglioni came out with the 750SS, a 90-degree, air-cooled L-twin with two valves per cylinder having desmodromic actuation. A new engineer, Massimo Bordi, replaced Taglioni in the early 1980s, and he began work on updating the L-twin, with liquid cooling and four desmo valves per cylinder. However, this was an expensive proposition, and it wasn’t until Cagiva bought Ducati in 1985 that Bordi had the money to do proper development. Much of that work was done at the Cagiva research center in Varese, 150 miles northwest of Bologna. And the result was the Ducati 851 model (Retrospective, July 2007), introduced in November of 1987, which grew to the 888 in 1993.

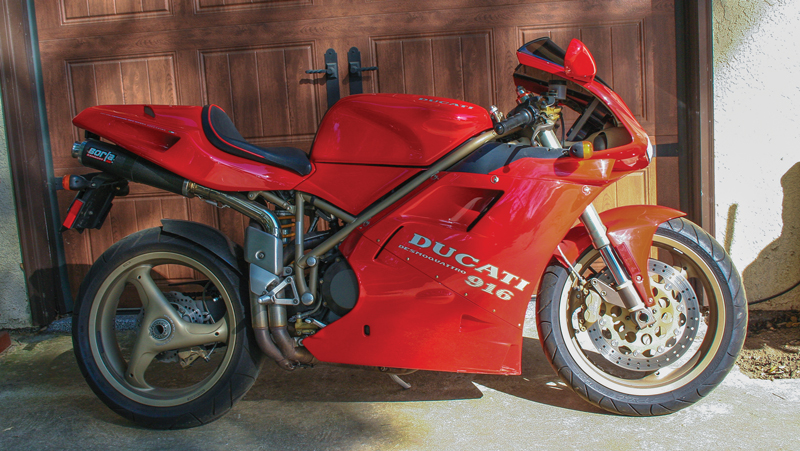

Another engineer, Massimo Tamburini, was the fellow who actually designed the 916, replacing the 888, the first one appearing in October 1993 at the annual Italian motorcycle show. Initially it had a very limited production run but it was such a success at the track that a clamor went up for more bikes. The 916 was only in production five years, but in four of them it won the Superbike World Championship as well as the Manufacturer’s Championship. Can’t do much better than that, a compliment to a great engine, great chassis and great riders.

The Strada version was a slightly humanized, but only slightly, street-legal variation, and the relatively wealthy riding public had a chance to buy one—expensive at $14,500, but a lot cheaper than Honda’s RC45 at $27,000.

The appeal of the 916 appeared to be a balance between performance and image, with practicality a distant third. The short-stroke engine (stroke: 66mm, bore: 94mm) revved happily to 9,000 rpm and churned out more than 100 horsepower at the rear wheel. With stock gearing that was good for 160 mph. Maintenance was essential, as the overhead cams were spun with rubber belts—which needed to be changed regularly. The Weber-Marelli fuel system injected mixture into the combustion chambers through 50mm venturi openings, with an 11:1 compression ratio. The geared primary ran the power through a dry clutch (delightfully noisy), then through six gears, and out via chain final drive.

The twin-spar trellis frame, with a direct line from the steering head to the swingarm pivot, was made of 28mm chrome-moly steel tubing, and the engine was a stressed member. An aluminum rear subframe was bolted on to hold the solo saddle…and under the tail section sat the easily accessible lightweight central processing unit. Anything heavy, like the battery or coolant container, was crammed into the centralized mass around the engine. That single-sided swingarm used a pivot bolt that ran through both the frame and the engine cases, creating a desirable stiffness in the whole chassis. It also facilitated tire changes, and used a single Showa shock absorber with all compression, rebound and preload adjustments, though an Öhlins upgrade was popular, as seen on the photo bike. Up front a 43mm Showa fork, also fully adjustable, coped with the bumps in the road. In this case “fully” means the rider also had one degree of adjustment in the fork angle, an unusual addition to steerability. A steering damper was attached in front of the gas tank and did its job well.

Seventeen-inch wheels had large 190/50 rubber at the back, much skinnier 120/70 at the front, with both Pirellis and Michelins being used. A pair of 305mm Brembo discs with four-piston calipers worked efficiently at the front, with a single 200mm disc at the back. Wheelbase was a tidy 55.6 inches, with a claimed wet weight, including 4.5 gallons of fuel, of 430 pounds.

A repli-racer is not concerned with the rider’s feelings, especially not the feelings in his bum. A cheerful hour on the road was about all a mere mortal wanted. The bike was bred for the track, and the street version did not give much comfort. A two-seater version, the Biposto, became available, but it was rumored that passengers were hard to find.

Beauty is said to be in the eye of the beholder, but most beholders of the 916 would agree that this was one outstandingly lovely creation, the pure aesthetics of it turning any head. The sultry lines of the fairing were a credit to the Italian notion of styling, set off by the dual headlights and the three-spoke cast Marchesini wheels.

Turn the key and the Termignoni exhausts (this owner has changed to Borla mufflers) would begin with a muted bark. Stand the bike up and the spring-loaded sidestand would snap up quickly—a feature some riders thought of as “kamikaze.” Lose your balance while trying to get the stand on the ground, and a rider could damage “one of the most beautiful motorcycles ever made.”

Pull in the clutch, down for first, and away you go. Perhaps not the most graceful of departures, as the 916 did not much like being under 4,000 rpm, but soon you are on the narrow, curvy two-laner you call your own, the exhaust note at high rpm saying that all is right with the world.

Of course, if one did not have to have the latest and greatest, Ducati’s low-price option was the 904cc 900SS CR for $7,625. But any red-blooded Ducatista was willing to take an extra mortgage out on the house to have the 916.

The 916 ranks as one of the prettiest bikes ever made, especially for a fully faired bike. In my opinion, the only other bike to come close was the ’05-09 Triumph Sprint ST which was also a stunner.

But for the pure essence of motorcycling, nothing really comes close to a raw, purposeful, bare bones bike, one with the mark of sheer simplicity of appearance. I’m talking Sportster, ZRX1200, Bonneville and the like. That’s what a motorcycle is supposed to look like.

Interesting – I have an 06 Sprint and a ZRX1100 (green/white/purple, the fastest colors!). No Ducati’s, though I would not pass up a decent 916 some day when I win the lottery.

Sprint ST?????

What planet full of drugs are you on????

My favorite of the 996 and my 916

To ride the roads is the 996

The 916 I like in corners