Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the September 1997 issue of Rider.

If an American company like Polaris is going to jump feet first into the motorcycle market with one bike in the late 1990s, it has to be with a cruiser. The trick was, how do you make that cruiser stand out in the veritable sea of V-twins, teardrop gas tanks and bobbed rear fenders already out there? In looking at and riding this early preproduction sample of the Victory V92C, it quickly becomes clear that, while the Minnesota manufacturer has given cruiser enthusiasts the style they want, the Victory is still a unique machine.

Polaris is keeping many of the new V92C’s specs close to the vest for now, but we pried enough information from it before press time to get a pretty clear picture of the bike and the direction in which Polaris plans to take it. (You can read more about that here.)

“The engine doesn’t look like a Vulcan engine and it doesn’t look like a Harley engine. It looks like a Victory engine.”

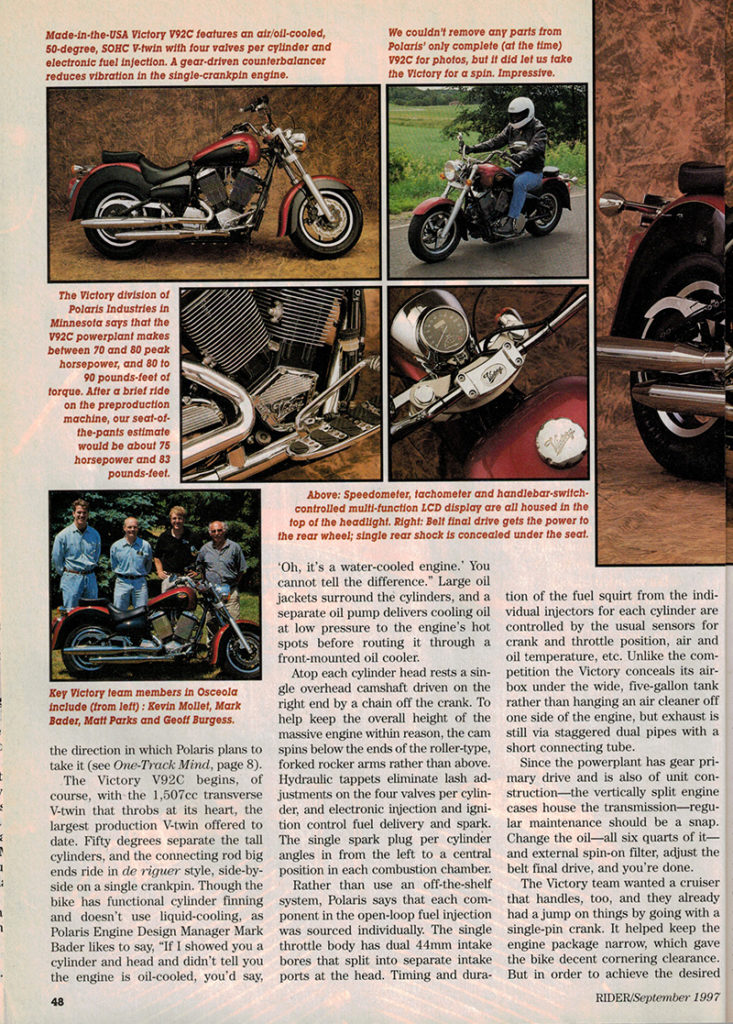

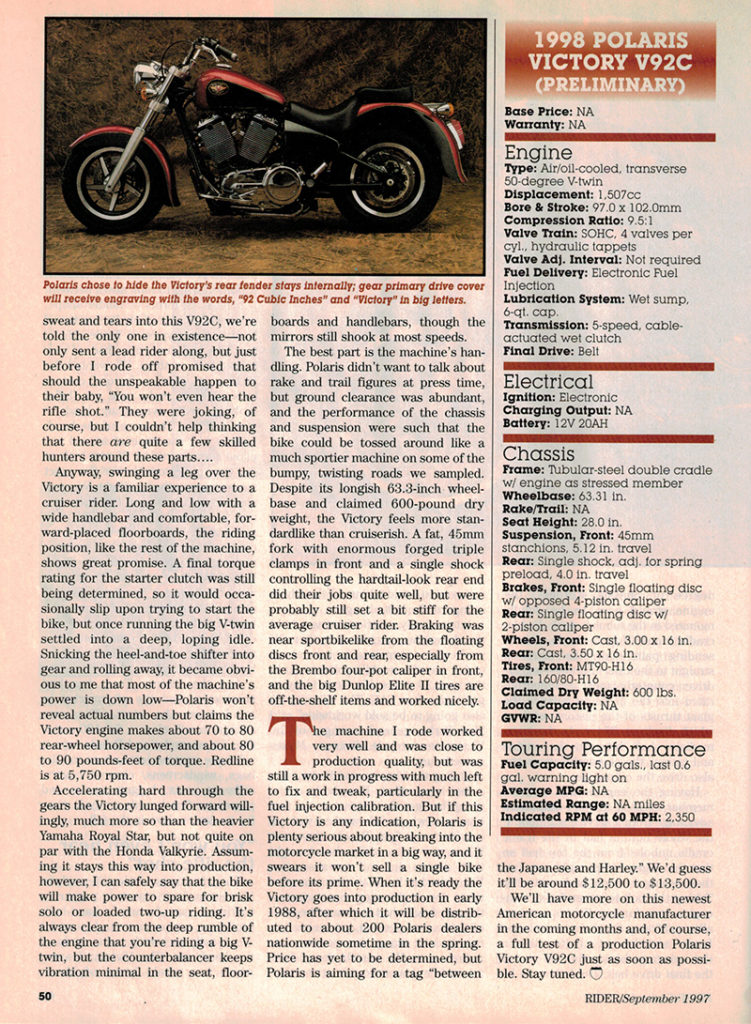

The Victory V92C begins, of course, with the 1,507cc transverse V-twin that throbs at its heart, the largest production V-twin offered to date. Fifty degrees separate the tall cylinders, and the connecting rod big ends ride in de riguer style, side-by-side on a single crankpin. Though the bike has functional cylinder finning and doesn’t use liquid-cooling, as Polaris Engine Design Manager Mark Bader likes to say, “If I showed you a cylinder and head and didn’t tell you the engine is oil-cooled, you’d say, ‘oh, it’s a water-cooled engine.’ You cannot tell the difference.” Large oil jackets surround the cylinders, and a separate oil pump delivers cooling oil at low pressure to the engine’s hot spots before routing it through a front-mounted oil cooler.

Atop each cylinder head rests a single overhead camshaft driven on the right end by a chain off the crank. To help keep the overall height of the massive engine within reason, the cam spins below the ends of the roller-type, forked rocker arms rather than above. Hydraulic tappets eliminate lash adjustments on the four valves per cylinder, and electronic injection and ignition control fuel delivery and spark. The single spark plug per cylinder angles in from the left to a central position in each combustion chamber.

Rather than use an off-the-shelf system, Polaris says that each component in the open-loop fuel injection was sourced individually. The single throttle body has dual 44mm intake bores that split into separate intake ports at the head. Timing and duration of the fuel squirt from the individual injectors for each cylinder are controlled by the usual sensors for crank and throttle position, air and oil temperature, etc. Unlike the competition, the Victory conceals its airbox under the wide, five-gallon tank rather than hanging an air cleaner off one side of the engine, but exhaust is still via staggered dual pipes with a short connecting tube.

Since the power plant has gear primary drive and is also of unit construction–the vertically split engine cases house the transmission–regular maintenance should be a snap. Change the oil–all six quarts of it–and external spin-on filter, adjust the belt final drive, and you’re done.

The Victory team wanted a cruiser that handles, too, and they already had a jump on things by going with a single-pin crank. It helped keep the engine package narrow, which gave the bike decent cornering clearance. But in order to achieve the desired degree of chassis stiffness, the engine would have to be solidly mounted in the tubular-steel, double-cradle frame. How to do so without sending paint-shakerlike vibration straight to the rider? Simple–a gear-driven counterbalancer was incorporated into the cases to balance the giant thrusts of the pistons, each of which displaces 745cc. As the intermediate shaft between the engine and tranny, the counterbalancer can also drive the oil pumps.

Having the engine as a stressed member created another important advantage from a service standpoint: the whole bottom half of the frame cradle unbolts from the top half so that the engine drops right out, further easing service and assembly. Taking the bolt-together frame concept a step further, Polaris used an alloy subframe for the seat and rear fender, and also put a bolt-on link in the swingarm beside the top run of the final belt drive. The latter can be removed to avoid taking off the whole swingarm for belt changes.

Interestingly, metric fasteners hold the American machine together. “If you’re going to make a decision about which way the world’s going to go in the next 20 years, it’s more likely to go metric than SAE. The (Victory is) also going to be sold worldwide,” said Matt Parks, general manager of the Victory motorcycle division. Makes sense to us.

Styling the Victory, said Parks, “was a real team effort. Everybody in the group has got they signature on that bike somewhere. We worked with an outside design firm (Brooks-Stevens in Wisconsin) for a while, then brought that design in and tweaked it–Victoryized it. It had to change several times for engineering concessions–the rear fender had to change because of the rear suspension, gas tank externals had to change to accommodate airboxes, etc. We went back-and-forth a lot when it was too this or too that. We wanted it to fit within the cruiser segment without looking like anybody else’s bike. There’s no fork tube guards or instruments on the gas tank by design. The engine doesn’t look like a Vulcan engine and it doesn’t look like a Harley engine. It looks like a Victory engine.”

Inspiration came from a number of places. “The floorboards, for example, are influenced by old race car pedals, all drilled and neat looking,” said Parks. “Older Japanese, German and British bikes put their speedometer/tachometer in the headlight, too. It’s a very clean look that still provides a lot of information without having to look down between your legs. In terms of fender shape, we looked at a lot of old Packards and Fords, those types of fenders from the ’30s, because they had a very classic look to them. We wanted the Victory to have a factory custom look, like an early race car, billet looking, with everything kind of extruded out. The cone of the headlight is like the cone of an old airplane turned around. If you look at our turn indicators they’re the exact same shape as the headlight. We even spent untold hours on the crazy gas cap because we knew exactly what we wanted. We said, ‘Remember the old Ford Apaches, how they had that really great gas cap with the finger holes?’ We drew it just about 20 different ways till we had it just right, then we also put it on the ends of the handlebars and the hubcap on the left side of the front wheel. So there are some themes that are throughout the bike, but they’re ours.”

And the Victory Team has had accessories and the aftermarket in mind from the start. The rear swingarm will clear a fat 180-series tire, for example, and Polaris says it will have accessories such as saddlebags, windscreens, chrome covers, different seats, luggage racks and passenger floorboards ready in time for its dealer show in the fall.

“You won’t even hear the rifle shot.”

They do things a little differently in Minnesota. In the past, in preparing to ride a manufacturer’s hand-built prototype, my promises to be careful are usually met with polite nods of the head, etc. The Victory Team–which has untold hours of blood, sweat and tears into this V92C, we’re told the only one in existence–not only sent a ride leader along, but just before I rode off promised that should the unspeakable happen to their baby, “You won’t even hear the rifle shot.” They were joking, of course, but I couldn’t help thinking that there are quite a few skilled hunters around these parts….

Anyway, swinging a leg over the Victory is a familiar experience to a cruiser rider. Long and low with a wide handlebar and comfortable, forward-placed floorboards, the riding position, like the rest of the machine, shows great promise. A final torque rating for the starter clutch was still being determined, so it would occasionally slip upon trying to start the bike, but once running the big V-twin settled into a deep, loping idle. Snicking the heel-and-toe shifter into gear and rolling away, it became obvious to me that most of the machine’s power is down low–Polaris won’t reveal actual numbers but claims the Victory engine makes about 70 to 80 rear-wheel horsepower, and about 80 to 90 lb-ft of torque. Redline is at 5,750 rpm.

Accelerating hard through the gears the Victory lunged forward willingly, much more so than the heavier Yamaha Royal Star, but not quite on par with the Honda Valkyrie. Assuming it stays this way into production, however, I can safely say that the bike will make power to spare for brisk solo or loaded two-up riding. It’s always clear from the deep rumble of the engine that you’re riding a big V-twin, but the counterbalancer keeps vibration minimal in the seat, floorboards and handlebars, though the mirror still shook at most speeds.

The best part is the machine’s handling. Polaris didn’t want to talk about rake and trail figures at press time, but ground clearance was abundant, and the performance of the chassis and suspension were such that the bike could be tossed around like a much sportier machine on some of the bumpy, twisting roads we sampled. Despite its longish 63.3-inch wheelbase and claimed 600-pound dry weight, the Victory feels more standardlike than cruiserish. A fat, 45mm fork with enormous forged triple clamps in front and a single shock controlling the hardtail-look rear end did their jobs quite well, but were probably still set a bit stiff for the average cruiser rider. Braking was near sportbikelike from the floating discs front and rear, especially from the Brembo four-pot caliper in front, and the big Dunlop Elite II tires are off-the-shelf items and worked nicely.

The machine I rode worked very well and was close to production quality, but was still a work in progress with much left to fix and tweak, particularly in the fuel injection calibration. But if this Victory is any indication, Polaris is plenty serious about breaking into the motorcycle market in a big way, and it swears it won’t sell a single bike before its prime. When it’s ready, the Victory goes into production in early 1998, after which it will be distributed to about 200 Polaris dealers nationwide sometime in the spring. Price has yet to be determined, but Polaris is aiming for a tag “between the Japanese and Harley.” We’d guess it’ll be around $12,500 to $13,500.

We’ll have more on this newest American motorcycle manufacturer in the coming months and, of course, a full test of a production Polaris Victory V92C just as soon as possible. Stay tuned.

Rider magazine. I just read your article about the seemingly first V92C Victory ever driven. I am the happy owner of such a vehicle with only 6 digits on the steering neck. And have a letter from Victory to verify this particularly bike is a an early version of the V92C. Therefore I like to ask the staff at Rider, if they know the frame number of the first V92C, namely the one test ridden in September 1997 . My motorcycle has number 8P6CB on frame and engine. Company representative from Polaris called my bike, “an early version” of Victory V92C. The bike was given to me as a present from a good friend in Wisconsin, and is now in Denmark.