The valley of death is a fascinating place—at least in my estimation. Having been there more than 40 times since my first visit in 1967, I’ve seen a lot of it. And during each visit I find something new to gawp at. Some people ride or drive through, with quick stops at Badwater and Zabriskie Point and say, “Been there; done that.”

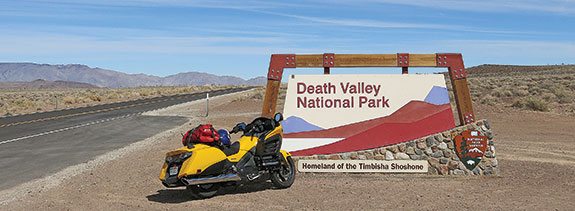

Except they haven’t seen a smidgen of what there is to see. This time around I thought I’d do a loop on all the paved roads, and describe what I’ve seen—and eaten. I’m riding with my friend Fireball and some 20 of our aging yuppie friends who have been coming out here annually for more than 35 years. I’m on the F6B, Honda’s notion of a stripped Gold Wing, while the others are on everything from BMWs to Harleys to Japanese and Italian sportbikes. My bright yellow bagger does stand out.

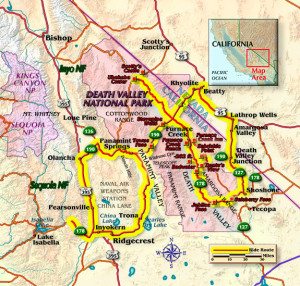

Coming from the west, we enter the Death Valley environs via Olancha, which sits on U.S. Route 395 at the intersection with California Route 190. We stop at the Ranch House Café, built before World War II, for some good, basic food. Those not concerned with calories go for the Indian fry bread dressed up with taco-style toppings.

Route 190 is by far the most spectacular approach to Death Valley National Park; 35 miles on you enter the park, cross over the Darwin Hills and are looking down, way down, into the Panamint Valley—which parallels Death Valley. Stunning views! And a stunning road, twisting down and down and down, with some very tight curves and U.S. Navy F15s making loops and runs down the valley to the China Lake bombing range.

At the bottom of the hills is the Panamint Springs Resort, a privately owned motel/campground/restaurant that was grandfathered in when the park expanded 20 years ago. A delightfully ramshackle affair, with 180 different beers in the cold case, it provides me with a sarsaparilla.

From the springs it is a dead-straight five miles to cross the valley and begin climbing the Panamint Range, with a well-paved road curving gracefully up the mountain slopes to Towne Pass, at almost 5,000 feet. There you get the first look at Death Valley, the view expanding as the road goes 17 miles down to Stovepipe Wells. The final five miles looks out over the valley and the Mesquite Flat sand dunes, back-dropped by the Amargosa Range.

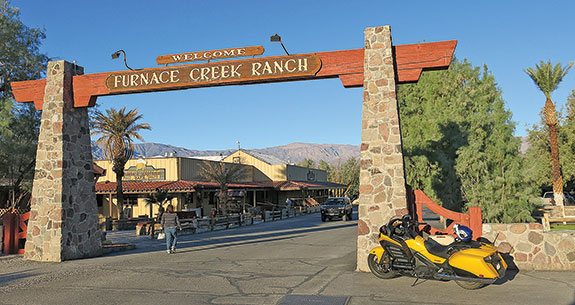

Stovepipe is one of two official resorts controlled by the U.S. Park Service, which leases them out to an outfit called Xanterra Parks & Resorts. At Stovepipe and Furnace Creek, the park headquarters, Xanterra runs all the concessions, from rooms to restaurants, shops to saloons. It is like this in most national parks, with private concessionaires doing the catering to the tourists. Death Valley doesn’t have entrance gates like many other national parks, but there are kiosks where you can pay the entrance fee ($10 for motorcycles or $20 for other vehicles for 7 days).

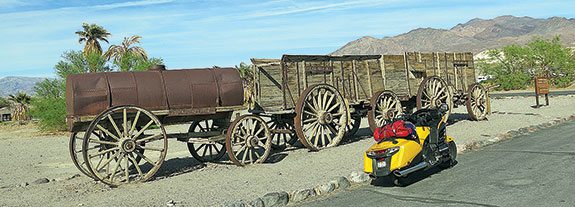

We all check into our rooms at Furnace Creek Ranch, which used to be called Greenland when it was the headquarters for a mining operation, Pacific Coast Borax Company. This green oasis is watered by a spring in the hills a couple of miles from the Ranch. Before the advent of tourism—thanks to air-conditioning—the only profitable business in Death Valley was the mining of borax in the late 19th century. And what is borax used for? Many things, like in the making of glass or as a household cleanser. Remember the 20-Mule Team Borax ads?

The park covers more than 500 square miles, with only three gas stations inside it, at Panamint, Stovepipe and Furnace Creek. The small towns on the roads that go around the park are also providers, but make sure you know your bike’s range. The F6B’s tank holds 6.6 gallons, so I am good for more than 200 miles—but I still fill up when I’ve gone more than 100 miles, just to be sure.

The next morning, I get up before dawn to ride 25 miles up to Dante’s View, at 5,500 feet, to see the sunrise. The sight is quite impressive, as 20 miles west of Dante’s directly across Death Valley is Telescope Peak, at 11,000 feet. And it has snow on top, so as the sun comes up behind me the view is phenomenal. Directly below Dante’s is Badwater, at 282 feet below sea level.

Fireball has a traditional 70-mile ride to Shoshone for breakfast at the Crowbar Café and Saloon. Lots of sluggards among us, but eight suit up and head down to Badwater, where we contemplate the feasibility of digging a trench 240 miles over to the Pacific Ocean and putting in hydro power. Not feasible. The pace picks up as we continue on to Shoshone, over Jubilee and Salsberry passes, and the F6B’s abilities do impress me. With a 66-inch wheelbase the turns over the passes are a bit slow, but the bike does nobly. The sportbikers are mildly surprised that I am hanging right with them. The flat-six tranny is typically slow in shifting, but with copious torque I don’t really have to change gears all that much.

We exit the park, and ride into the very little town of Shoshone—Crowbar Café, Charles Brown’s store and gas station, post office and campground. Don’t ask what I had for breakfast; my cardiologist would not approve.

Back in the saddle we head off to Death Valley Junction, once the site of a thriving railroad conglomerate, now best known for the Amargosa Opera House. That is at one end of a large, U-shaped building built in the 1920s to house railroad workers, which now has a hotel and café. A dancer and artist named Marta Becket bought the place in the 1960s, fixed it up and gave performances. Marta retired in 2012, but the opera house still stages song and dance revues on Saturday evenings—though not in summer.

Everybody else is heading back into Death Valley, but I’m going to do my full loop around it. A seven-mile straight leads to the Nevada border, and I crank the bagger up to two miles a minute—rock steady. With that short windshield, the F6B is really noisy, but earplugs quiet it down to acceptable levels. Were I to take this bike on a seriously long trip, I would certainly get a bigger shield, but for this thousand-mile jaunt I am quite happy.

On to Beatty, which was best known for its gold-mining days that are long past. Now it mines tourists, both at the two casinos (we’re in Nevada) and at Angel’s Ladies, an outfit profiting from the world’s oldest profession until it closed in August of 2014.. The place is just north of town, identifiable by a big sign and a wrecked Beechcraft 18. The house of ill repute bulldozed a landing strip for those in a hurry, and the pilot of this Beech must have been overly excited when he landed.

I stop for gas and next door is the Chamber of Commerce—always a good place to gather info. I say I am headed up U.S. Route 95 to Scotty’s Junction, and then down to Scotty’s Castle in the park. Sorry, the 25 miles of road from the junction to the Castle is definitely closed while being repaired. All right, I’ll go back to Death Valley via Daylight Pass Road and north to the Castle.

On the way I stop at Rhyolite, where gold was discovered in 1904. Boomtown! Big buildings went up, the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad arrived in 1906—but by the time we got into World War I the pickings were pretty much played out. Now you can admire the ruins of the old bank, the railroad station and the house built from 30,000 glass bottles.

Leaving Rhyolite I head west over Daylight Pass at 4,300 feet, and then the long downhill into the valley, take a right, and it’s 35 miles to Scotty’s Castle. Scotty’s is probably the primo attraction in Death Valley, with over 100,000 visitors paying to take guided tours every year (buying tickets in advance is recommended). Visiting the castle is free if you just want to look at the outside, which has fancy Spanish Mission-style architecture. It was built in the 1920s by a Chicago millionaire and looked after by a charming conman named Walter Scott.

I get as far as the turnoff to the Ubehebe volcanic crater, three miles from the castle, and an attractive young woman is holding a STOP sign. Road construction; it will be a half-hour wait. And if my timing isn’t perfect I’ll have a look at the Castle, and then have to wait half an hour at the other end. I’ve been there before, many times, taken two tours—I can skip it.

A short run takes me up to the crater—a big hole in the ground—and back to Furnace Creek for a swim in the pool. That night some go to the Wrangler Steakhouse and have $40 steaks ($15 in Beatty), others to an outdoor barbecue at the museum ($27 plus $7.50 for a glass of box wine), and half a dozen of us to the 49er Café for burgers.

Morning and I am up at a reasonable hour to ride the two miles to Zabriskie Point where, along with 30 other tourists, I admire the morning light show in the badlands. About a million people come to Death Valley every year, and the majority go to Zabriskie, even though it is not nearly as wonderful as Dante’s View…just more convenient.

We’re packing to leave. I want to go out via Wildrose Canyon and see the old charcoal kilns, but it turns out the canyon itself is closed due to flooding a few weeks before. The kilns were built back in the late 1870s when prospectors, hoping for a major gold or silver find, needed charcoal to smelt the ore. Only a couple of small mines opened up, and they quickly played out; the kilns were apparently abandoned after only two years.

Since Fireball and I won’t be doing Wildrose, we exit the park via Panamint Valley. We stop for breakfast in the mining town of Trona, which sits next to a dry lake full of the sodium-rich mineral for which the town is named. From borax mining in Death Valley in the 1880s, we now have trona mining in the 2010s.

And how did the bagger do? Quite well. It’s intended to be an urban bagger, cruising Main Street where style is more important than function, hence the minimalist windscreen. But it is also fine for a trip like this. Just remember the earplugs.

(This article Flying Low Over Death Valley was published in the May 2015 issue of Rider magazine.)

|

|