Carl Stearns Clancy had a curious mind and a restless soul. Growing up in New England at the dawn of the 20th century, this wayward son of a preacher would comb cemeteries in search of amusing epitaphs. In 1908, he followed his older brother George to Syracuse University, only to conclude that, “College seemed awfully dull.” Not even bustling New York City, where he settled to work in advertising, offered a cure for his doldrums.

Only one aspiration consumed him—to accomplish “the longest, most difficult and most perilous motorcycle journey ever attempted.” In short, to “girdle the globe” on two wheels.

Indeed, that was no trivial task in 1912, a mere 18 years after Frank Lenz had disappeared in a remote section of Turkey, attempting a similar feat on a motorless two-wheeler. Roads were still generally unpaved, international communications remained spotty and gas stations were virtually non-existent.

Undaunted, Clancy found just the backers he needed in George and Thomas Henderson. A year earlier, these brothers from Detroit unveiled an upscale 4-cyclinder, 7-horsepower motorcycle bearing their surname. The 57-cubic-inch engine ran about 50 miles per gallon of gasoline and about 175 miles per quart of oil. The vehicle had a hand-crank starter and one foot-operated brake, acting on the rear wheel.

Among its novel features were a fully enclosed chain drive, immersed in an oil bath, and an elongated frame with a 65-inch wheelbase that allowed for an optional passenger seat on top of the 3-gallon cylindrical gas tank, between the driver’s seat and the extended handlebars.

The young industry received the Henderson with skepticism, but the brand quickly gained a reputation for speed. Still, given its whopping $325 price tag (several months salary for the typical workman), the brothers fully understood the need for aggressive advertising. Their early ads employed alliterative slogans such as “Silence, smoothness, and sweetness of running,” and coyly suggested that females would find the passenger seat irresistibly seductive.

The Hendersons authorized Clancy to set up dealerships wherever he went. He stood to make a healthy $5 commission per motorcycle on every order he brokered. Moreover, Bicycling World and Motorcycle Review agreed to pay him for periodic reports. Finally, he persuaded a buddy, Walter R. Storey, to acquire a Henderson and join him on the adventure, though he had no motorcycling experience.

Preparing for several months, the two assembled an assortment of wrenches, a first aid kit, a folding typewriter, film and movie cameras, and a silk balloon tent. For security, Clancy packed a Savage revolver. They made contingency plans to have tires, gasoline and lubricating oil shipped to the “uncivilized districts” where such high-tech products were as yet unavailable.

To gain access to road maps and travel information, they joined a host of touring clubs. To open doors, Clancy carried letters of introduction from William Jay Gaynor, the mayor of New York City, and President William Howard Taft.

Sailing to Dublin, Ireland, in October 1912, the lads caught up with their brand new machines shipped directly from the factory. Their tour of the Clancy ancestral homeland began disastrously. First, Clancy learned that the Henderson importers in London had already placed an order for 200 machines without his help. Then, just as the tourists were motoring out of the Irish capital, a double-decker tram squashed the rear wheel on Storey’s motorcycle. Consigning the broken machine to a bicycle shop for repair, Clancy and Storey rode two-up with 75 pounds of collective gear on the good machine.

Heading inland toward the county of Donegal, the rugged northwest corner of Ireland, they cruised at a 20-mph clip over level roads. They dodged cattle, sheep and other roving creatures and suffered occasional spills. To replenish their petrol, they frequently had to search on foot for a hardware store. Still, the ancient stone huts, breathtaking landscape and poor but cheerful populace more than compensated for their travails.

From Belfast they sailed to Glasgow, then they crossed the Scottish highlands on two machines. After pausing at Gretna Green, the famous eloper’s chapel, they entered England by way of the Lake District. Passing through Birmingham, they toured the coal rich “Black Country.” Wherever they stopped, large crowds gathered to admire their massive machines and remarkably fat Goodyear tires.

In the ancient university town of Oxford they spied the young Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII. In London, they visited the plush headquarters of the Royal Automobile Club, where they granted an interview to Motor Cycling magazine.

Sailing to Rotterdam, the two began their tour of the European continent, passing through the Belgian countryside which would soon be decimated by World War I. Reaching Paris in time for Thanksgiving, they settled down to reassess their plans.

Things were not going well and Clancy knew it. His funds were depleted and his partner opted out. Though Clancy would publicly maintain that Storey had been summoned back “imperatively” by his employer, Clancy’s mother privately gave a different explanation. Writing to her son George she confided, “[Storey] is sort of an artist, and wants to stay [in Paris] to paint.” Even Clancy’s parents urged him to abandon his quest and return home himself.

In early 1913, buoyed by an order from a Paris dealer and Henderson’s promise to pay him $500 should he reach Japan with his motorcycle, Clancy vowed to continue on alone. He made a few preparations, such as replacing his tread-bare tires. When Goodyear originally sent him the wrong size tires from its factory in Akron (he needed 39 x 8 ¾ inches), the company apologetically sent Clancy another pair and refunded his $9.75. Before long, Clancy was on the road again, touring the magnificent Loire Valley with its splendid chateaux, and streaking south toward the Pyrenees.

Spain was something of a low point for Clancy, starting at the border when customs officials demanded an outrageous $50 fee based on the weight of his vehicle. The roads were abysmal and the petrol was the priciest he had yet seen (about 90 cents a gallon, quadruple the typical price at home). Then his Henderson broke down. Hearing a strange knock in the motor, Clancy diagnosed the problem as a broken crank bearing. Fighting off a crowd in the ancient town of Figueras, Clancy guided his lame machine to a bicycle shop where it would remain for three days, pending the fabrication of a replacement.

of the Coeur d’Alene mountains.

His European excursion at an end, Clancy had already overcome numerous challenges. Still, the Old World had presented relatively familiar western cultures, in which his English (along with his rudimentary French) generally sufficed for communications. Clancy knew well that his real adventures would begin once he set foot in Northern Africa and skirted the rugged coastline between Algiers and Tunis.

Almost on cue, somewhere between those points, a gang of six Arabs on ponies suddenly appeared and gave chase, firing their rifles in Clancy’s direction. Fortunately, he managed to outride his pursuers, reaching a “safe” haven (a mountain pass with a 100-foot drop-off).

Clancy abandoned the idea of riding across China when he learned that the roads there were impassable, and confined most of his Asian riding to the tropical island of Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka). Bumping along jungle paths, he had several near fatal run-ins with water buffalos and cheetahs. At night, he found his tent surrounded by jackals and mountain cats.

Japan’s narrow and twisty roads, affording constant vistas of mountains and streams, limited Clancy’s pace to about 15 mph. But he was in no hurry, pronouncing Nippon “the most fascinating country in which to motorcycle. Everything is so different, so beautiful, so peculiar in its charms.”

In May 1913, Clancy arrived in San Francisco. There, he began his final 5,000-mile push across the United States, accompanied by Robert Allen of Los Angeles, who rode a revamped 1913 Henderson.

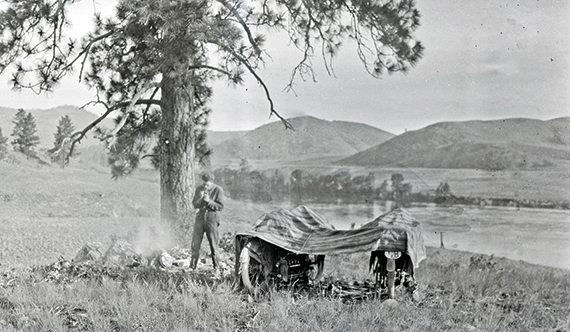

Near Portland, Oregon, Clancy encountered the worst roads he had seen the entire trip, full of rocks and mud. Some days the two barely covered 20 miles. During one brutal two-hour stretch across the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana, Clancy fell 17 times.

The pair spent five days touring Yellowstone Park on foot, while a mechanic in Livingston repaired Clancy’s broken front fork. In Beloit, Wisconsin, Clancy visited his brother George and his infant nephew Edward (who recently turned 100). In the Berkshires of Massachusetts, Clancy stopped to see his much-relieved parents.

In late August 1913, Clancy triumphantly returned to New York City astride his battered but still functional Henderson. He thus completed the first official “round the world” journey by motorcycle, having ridden some 18,000 miles on three continents in 11 months. Yet, despite the flurry of newspaper articles that materialized in his wake, his fame as a motorcyclist proved short-lived. He never would accomplish his original plan to turn his meticulous notes into a book.

Fortunately, however, his original manuscript and numerous photos have been preserved. After Clancy died in 1971, his former housekeeper inherited the collection and passed it on to Liam O’Connor, an inquisitive boy in the neighborhood who used to drop by the Clancy residence in Alexandria, Virginia, to hear “Mr. Clancy” tell of his adventure long ago. Now a medical professor at the University of Western Australia in Perth, O’Connor recently donated his Clancy materials (including a pair of boots Clancy wore en route) to the Smithsonian Institute at the invitation of the Clancy family.

Clancy went on to a distinguished career in film, but he will no doubt be best remembered for this historic ride a century ago. Although he would express regret at losing his partner Storey (“Much of the fascination of the motorcycle,” he wrote, “lies in the spirit of companionship that it encourages”), he was confident that he had achieved his main objective—to prove that a “round the world” journey by motorcycle was not only possible but also enriching. “I feel safe in saying,” he concluded, “that by no other means could I have obtained [such a] broad insight into conditions in foreign countries.”

Editor’s Note: David V. Herlihy is the author of Bicycle: The History and The Lost Cyclist. The author would like to give special thanks to Liam O’Connor and the Clancy family for sharing archival materials.

(This article Clancy’s Conquest was published in the August 2014 issue of Rider magazine.)