As our early-morning flight from Miami descended into the Havana airport, the pilot came on the PA: “Ladies and gentlemen, we will be landing in a few minutes. I suggest that you turn your watches back 50 years.”

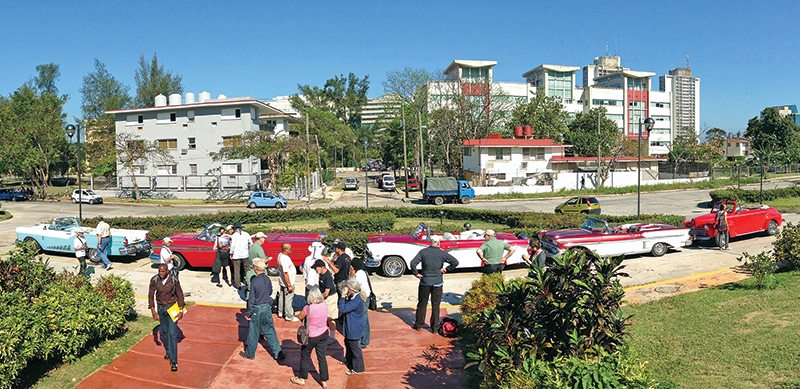

Once the 16 of us had collected our luggage, cleared Cuban customs and headed out to the tour bus, we soon discovered that the pilot was spot on—we had just traveled back in time. The airport parking lot was full of colorful four-wheeled relics from the 1950s. Chevrolet, DeSoto, Ford, Kaiser and their kin were the norm; we even spotted a Pontiac Chieftain convertible. Turns out riding in Cuba is like taking part in a vintage car rally…everyday!

These Detroit gems are the cars families owned before the Fidel Castro-led Cuban Revolution in 1959, after which the U.S. instituted a total embargo. For the most part, Americans haven’t been allowed to visit since. That’s beginning to change, so this ride truly was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. We all wanted to visit Cuba while it is still an emerging destination for Americans. Friends had been there on cultural tours with music or art groups. Others had come on church or medical missions. For our adventure, Skip Mascorro of MotoDiscovery spent three years working with the U.S. State Department to vet and license a series of “People-to-People Cultural Exchange” motorcycle tours. There’s no beachcombing or hanging out at resorts on the menu as such; the idea is to rub elbows with regular Cubans—shopkeepers, farmers, artisans, homemakers—and get to know the real Cuba.

After we landed, the bus took us to a pleasant open-air restaurant where we enjoyed our first taste of Cuban cuisine: roasted chicken, beans and rice. A live ensemble playing energetic Cuban salsa beats accompanied virtually every lunch and dinner. Because it’s mostly off-limits to Americans, there’s an assumption that the tourism infrastructure is inadequate, so our expectations were low in terms of the food and accommodations. That turned out to be completely wrong. Canadians, Europeans, South Americans and Asians flock to Cuba in droves. Foreign currency backstops the Cuban economy, some of which is evident in the beautifully restored, centuries-old Spanish Colonial buildings.

The first ride on our newer BMW F 800 GS and R 1200 GS motorcycles was on well-maintained roads along the Caribbean, with palm trees swaying in the gentle breeze under cloudless blue skies. We entered the city of La Habana, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, via wide boulevards to Revolution Square, with its large parking areas where there are frequent displays of military might. Luis, our local guide, told us that before the breakup of the USSR, joint Russian-Cuban military exercises were a show of strength to thwart any American threats. If all of the signs, posters and giant silhouettes of him on buildings are any indication, revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara, Castro’s second-in-command, is more revered than Fidel.

That night we enjoyed a memorable dinner in a private residence (paladares) turned restaurant. This is a relatively new phenomenon instituted under the liberal guidance of Raúl Castro. The Cuban entrepreneurial spirit is alive and well, with many policy changes allowing ambitious people to enjoy prosperity. Many of us ordered the lobster, which was on at least three other menus during our nine-day tour. As an island nation, seafood was always available.

After a giant breakfast of fresh fruits, juices, breads and pastries, we rode on suburban streets to the Ernest Hemingway memorial overlooking his beloved ocean. Our tour guide told us that it was here, adjacent to a small stone castle, that “Papa” was inspired to write The Old Man and the Sea. Fascinated by the unusual sight of our large group of new BMW motorcycles, the police stopped to see what we were doing. They were very friendly and wanted photos with all of us Americanos. It was the People-to-People program in action, although they were the only policia we encountered on the whole trip.

hombre at the Moro Fortress merengue lunch.

Shortly after this stop, we took a narrow serpentine road up to Finca Vigía, Hemingway’s former villa that is now a museum. Everything is exactly as he left it to the Cuban people, and lots of tourists come to visit the various memorials to his writings. Then our motorcycle city tour brought us into the center of Havana, a metropolis of 2 million, via a series of well-manicured boulevards. Perhaps the best part of the day was a long coastal ride out to the Moro Fortress, which sits on a narrow peninsula guarding Havana harbor. We climbed around the colonial cannons, and then made our way down to a little outdoor café. Within short order, the merengue band had all 16 of us dancing our lunch away.

The next day we headed 65 kilometers west on Highway N4 before turning north to Las Terrazas, an ecological reforestation area. After 26 years of conservation, it has become a forest preserve for city folks to enjoy. The riding on twisty foothill roads was great fun, with huge canopies of trees providing welcome shade. We did not see any other vehicles other than a horse-drawn wagon for the next hour. It was a visual and riding paradise, and we had the hills to ourselves.

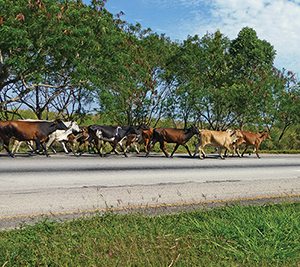

Then we endured a slog of 400-plus kilometers east on Highway N1 to get to Santa Clara. This six-lane divided highway, like N4, has long, straight sections intended to serve as emergency airfields if needed for defense. Again, there were hardly any cars, but the numerous cattle being herded on the highway made for some breathtaking moments!

Santa Clara would be our staging area for several explorations, including a visit to what used to be a major sugar-processing factory. In pre-revolutionary times, the U.S. imported more than 400,000 tons of sugar from Cuba annually. There was an elaborate narrow-gauge rail system that brought all this refined sugar from the hinterlands to the seaports. Once the U.S. realized that Fidel had strong Communist leanings, it cut back on Cuban sugar imports, turning to alternative sources such as sugar beets. Now the trains and factory are a museum of this former cornerstone of the Cuban economy, replaced with tourism.

The Che Guevara Mausoleum was next on the agenda, in a park in Santa Clara, the town where Che literally derailed the Batista government troop train carrying reinforcements to Havana. Che knew about the train and drove a bulldozer across the tracks while his revolutionaries ambushed Batista’s unsuspecting loyalist soldiers. There are two memorials, one with the bulldozer near the tracks that illustrates the legend, and the other a giant bas-relief facade in a lush, well-manicured park depicting Che and his fellow revolutionaries.

The most challenging riding of the trip was headed directly south to the coastal town of Trinidad on very narrow, steep, serpentine roads with frequent Peligroso signs. It wasn’t that dangerous, but the road had lots of potholes in all the wrong places. The change in elevation from a high plateau to sea level was about 1,400 feet over a 6-mile distance. It added a bit of excitement to the ride compared to the perfectly graded roads in other rural areas.

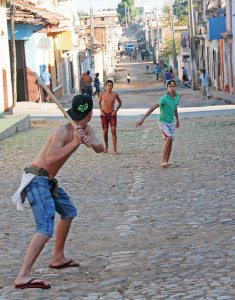

In Trinidad, we watched as many of the locals played dominoes, a Cuban national pastime. Whether on a table in the street or under the shade of an open station wagon rear door, it was fascinating to watch as each player put down his domino with a disdainful click. The other pastime here is baseball, and we saw several games being played on our ride back from the sugar factory and in the cobblestone streets of Trinidad.

As part of the P2P experience, rather than stay in a government hotel 60 kilometers away, our guide, Juan Stanglmaier, arranged for a series of Trinidad “home stays” in private homes, which gave us the opportunity to see how the people live. Our rooms were clean and simple, and we had breakfast with the family the next morning. Using broken English and sign language, we were all able to communicate and enjoy being with our hosts.

On our ride back to Havana we got rained on for an hour, so at dinner Juan explained that for our next Havana city tour the following day, rather than ride around in wet gear, he had arranged for “alternative transportation.” As a former tour guide, I suspected that meant he was unable to get a bus and that we would be relegated to horse-drawn carts, tuk-tuk scooter taxis or some clapped-out Lada taxicabs. I said nothing and waited to see what fate would deliver.

After breakfast, five restored Detroit convertibles drove up to the hotel. Juan’s solution was much better than a bus! The lead driver gave a short orientation about the cars. When I asked him why his English was so good, he pulled out his Florida driver’s license. Asking him why he left, he said, “There is no crime in Cuba and better opportunities for success!”

This tour was definitely an eye-opener, not to mention a great ride and a genuine trip back in time.

MotoDiscovery offers Cuba tours of nine or 15 days. For more info visit motodiscovery.com.

About the Author

At age 50, Burt Richmond left the large architectural firm he founded to start Lotus Tours, so that he and his clients could experience the world on two wheels, traveling to more than 100 countries. Today, Burt is a frequent participant in Motogiro d’Italia, organizes microcar exhibits for auto shows and the Vintage Motorcycle Festival (vintagemotorcyclefestival.com) every August at the LeMay—America’s Car Museum in Tacoma, Washington.

(This article So Near Yet So Far was published in the May 2014 issue of Rider magazine.)

|

|

Beautiful review, I would love to visit Cuba