Click here to see and download the Natchez Trace Parkway route on REVER

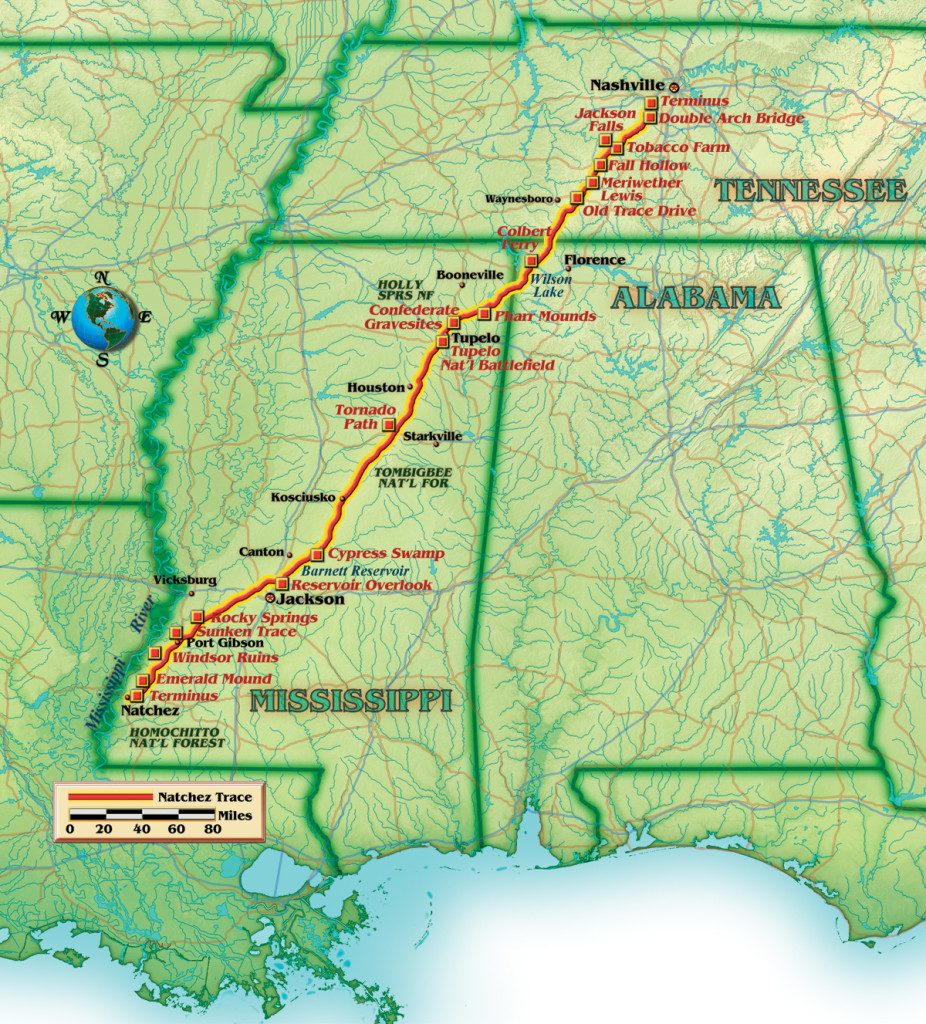

Rod Serling’s words ran through my mind as I turned off Highway 61 to enter the southern portal of the Natchez Trace Parkway: Next stop, the Twilight Zone. Well, the Trace isn’t quite that odd, but it is a world unto itself. This 440-mile strip of Mother Nature is devoid of commercial traffic and billboards. It’s a sinuous, two-lane parkway, haunted by ghost towns and the graves of Confederate soldiers yet graced by abundant wildlife and natural beauty, that heads northwest from the Mississippi Delta, through a corner of Alabama to the rolling hills of Tennessee.

This is one of the oldest routes in America, with origins that go back some 8,000 years. It began as a migratory path for buffalo and other wildlife moving north and south. It then served as a “main street” for a variety of Native American tribes. In the early 1800s, before steamships, farmers and boatmen from the Ohio Valley used the path to return north after delivering their goods to southern ports via the Mississippi River. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the legislation to create the modern-day Parkway in 1938. The Civilian Conservation Corps built it, and today the National Park Service oversees it. The final segments were opened in 2005.

The 50 mph speed limit in force the entire length of the Parkway sounds boring, but here’s the magic: This is a glassy-smooth and uncrowded road, twisting through a gorgeous natural environment, embracing centuries of history and attracting a collegial community of travelers.

Planning a ride on the Trace is straightforward; it’s perfect for a two-day journey. Of course, you could cover the entire stretch in one very long day, but why rush through paradise? Tupelo is close to the halfway point and makes a logical layover site. I took my ride in early May, well before summer tourists flock to the area. Plan your gas stops carefully—there is no gas available on the Trace itself so you’ll have to jump off to fill up. Finally, check out the many resources available on the web to customize your daily itinerary. Key attractions are easily located using mile markers.

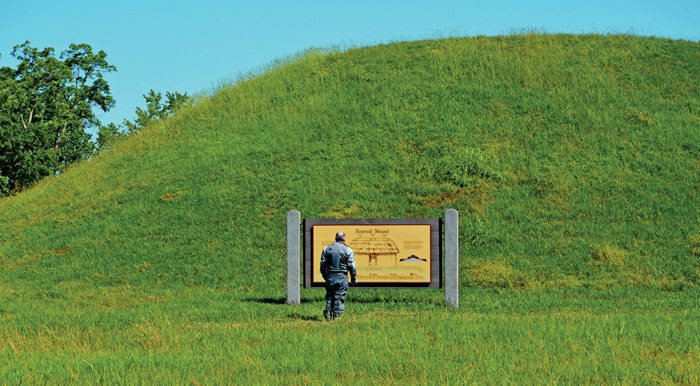

I made the two-day run beginning at mile zero, traveling north and leaving Natchez under an azure sky. The first 20 miles of the Trace undulate through a dense, hardwood forest. Tall, old-growth trees standing sentinel on either side of the Parkway thwart the hot Mississippi sun. Early in the ride, I learned about the Native American heritage of the region at the Emerald Mound (mile 10). Rising out of a field is the second largest temple mound in the U.S. The eight-acre hill was built and used from 1300 to 1600 by the Mississippians, ancestors of the Natchez tribe. On important occasions, it was the scene of processions, ceremonial dances and religious rituals.

At mile 19, a small doe sprinted across the road. Deer aren’t a major problem until twilight, when extreme caution is warranted as herds of animals congregate on roadside berms. Daytime challenges include bicyclists and distracted car drivers. Ride defensively and be aware of a new law that requires motorists on the Trace to give bicyclists a buffer zone of at least 3 feet.

If time permits, take a short side trip to Port Gibson, just west of the Trace at mile 40, and check out the ruins of the Windsor Plantation. The mansion, built by slave labor in the early 1800s, was the largest antebellum Greek revival mansion built in Mississippi, and has been used as a backdrop for several popular movies.

The paved Trace doesn’t overlay the original trail precisely. The old path meanders back and forth across the modern Parkway, and a mile north of the Port Gibson exit (mile 41) is the first opportunity to take a short hike to check out the old trail. You’ll find that this section of the “Sunken Trace” is cut a dozen feet into the earth as a result of years and years of boots, hooves and wagon wheels trampling the easily eroded loess soil.

Cruise north another dozen miles or so and look for the ghost town of Rocky Springs (mile 55). First settled in the late 1790s, it is named for its sweet flowing water and rose with the fortunes of the cotton crop. By the early 1860s, it was home to more than 2,600 people. Today, the spring is dry, and only a church and cemetery, two rusty safes and a few old cisterns remain. The town fell victim to the Civil War, an outbreak of yellow fever and poor farming practices.

Ride another 50-mile segment, then stop to enjoy the view from the Ross Barnett Reservoir overlook (mile 105). Don’t miss the tupelo-bald cypress swamp at mile 122. A long, wooden boardwalk puts you just inches above the water as you stroll among the wildlife. Walking on the boards, I met a rider from California who shared his dream of taking Route 6 cross-country. I didn’t doubt his aspiration: His license plate (HWY 6) was mounted in an Iron Butt frame.

As I left the swamp and continued north, I had to ride in a driving rain until it turned to a drizzle somewhere around mile 200. The stretch between mile 205 and 210 made me glad I wasn’t on the road in April 2011 when a powerful tornado tore through the area. The swirling winds snapped off thousands of trees like matchsticks, leaving behind an eerie forest of jagged 10-foot stumps.

The rain came back with a vengeance, pounding me until the Tupelo exit at mile 260. I staggered off the bike at the Best Western Plus, grabbed a hot shower and had a cold drink at the Chili’s next door. It was a good end to a great day. The Best Western earned two thumbs up. It is nearly new, convenient to the Trace and very rider friendly.

I awoke to sunshine, shared a hotel breakfast with a group of riders from Detroit, and did some minor bike maintenance until the roads dried a bit. I couldn’t pass up a quick ride to Elvis Presley’s childhood home in Tupelo before resuming the journey north.

Just up the Trace from Tupelo are the graves of 13 unknown Confederate soldiers (mile 269). Speculation is that the men died defending the nearby headquarters of General J.B. Hood. The original grave markers were lost, and the National Park Service erected the marble headstones now in place. Each gravestone was adorned with flowers and accompanied by Confederate flags.

Farther up the road I encountered Pharr Mounds, another sacred Native American site (mile 287). Eight dome-shaped burial mounds are scattered over an area of 90 acres. Archeologists believe that the site traces back to earlier than 200 A.D.

The scenery along the Trace begins to transform in northern Mississippi. Woodlands give way to farmers’ fields and large meadows lush with wildflowers. North of the Alabama state line, the road becomes hillier and you notice more roadside rock formations. Once into Alabama, I crossed one branch of the infamous Trail of Tears. Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Federal government ousted entire tribes from their eastern native lands and marched them to “Indian Territory” in Oklahoma. Thousands perished during the exodus, which the National Park Service now calls a “journey of injustice.”

A simple two-lane bridge crosses the broad Tennessee River at mile 327. In the early 1800s, George Colbert operated a ferry at this site. Legend has it that Colbert once charged Andrew Jackson $75,000 to transport his Tennessee army across the river after Jackson’s victory in the 1815 Battle of New Orleans. Today, Colbert’s Landing is the ideal site for a picnic or to simply sit on the riverbank and contemplate the current.

A bit farther up the road, I had the opportunity to journey into the past. I turned off at mile 375 and rode down a section of the “old Trace,” the original walking path. The narrow, gravel path meandered through deep forest. It was a nice change of pace, and gave me some idea of the peaceful solitude the old travelers experienced. These rugged vagabonds averaged between 15 and 25 miles per day by foot or horseback.

The life and death of Meriwether Lewis, senior commander of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and a governor of the Territory of Louisiana, is interwoven with the history of the Trace. Lewis crossed the Trace many, many times, and was shot to death at an inn just west of mile marker 386. The identity of the assassin remains a mystery to this day. An impressive monument stands guard over his grave.

There are two notable waterfalls on the northern portion of the Trace, at mile markers 392 and 405. You might have more luck than I did as low water levels in May led to disappointing views.

About 40 miles from the northern terminus, the Parkway grows more mountainous. Over its entire length, the elevation of the Trace varies between 70 and 1,100 feet. In Tennessee, wild turkeys pick at the roadside grass, undaunted by passing traffic. Look for the turnout at mile 401 and take a short tour of a reconstructed tobacco farm, then continue your ride on a narrow, two-mile section of the original Trace.

Several miles south of the northern gate, I passed over the Natchez Trace Parkway Arches. The structure rises 155 feet above the valley. Downshift a gear and feel free to gawk at the incredible view. Stop at the viewing area just north of the bridge and pause to reflect on this beautiful piece of engineering. The double-arch span is a unique design that was honored as the “single most outstanding bridge-building achievement of 1994.”

So ended my Natchez Trace odyssey. Rod Serling was right; I did enter another dimension. I particularly enjoyed the scenery along the Trace—two days immersed in a thousand shades of green. I loved puttering along at 50 mph for most of two days. It led to a peaceful, mental calm. And I really enjoyed meeting my fellow Trace travelers, like the Quebec bicyclist who averaged 70 miles a day. And George, the Honda-riding sheriff’s deputy from Florida. Or the gang from Detroit I met at the Best Western in Tupelo. And the Iron Butt rider from California. And the Alabama bicyclist who borrowed my toolkit to fix his ride.

You can travel the same road and have a totally different experience. Spend more time studying history. Take in more of the abundant wildlife. Spend a night camping. The rich environment of the Trace allows one to custom tailor a unique experience. Isn’t that what life on the road is all about?

I rode this wonderful road on my first long distance ride that covered approximately 2200+ miles over about 7-8 days. It’s a wonderful relaxing ride not only devoid of traffic snarls and people hurrying to nowhere in particular, but spotted throughout with tremendous sites of interest to both Civil War buffs and just those interested in how their forbearers lived in the 1700-1800’s. I’d ride it again in a heartbeat.

Bob, What time of year did you ride the Trace? I am planning a trip to the Ozarks from Maryland and I’m thinking of making this part of the trip. We plan on going the end of May.

It’s been 7 years since I made that ride but it was in late Spring early Summer. The weather was good with no hot days to contend with. The road is well shaded in any case and you’d never know that in most cases you’re not more than 1/4 to 1/2 miles from civilization as they’ve left a lot of buffer. It’s not like the Tail of the Dragon and it certainly isn’t anywhere near as commercialized as the Blue Ridge or Skyline Drive but it’s as I stated a relaxing ride through some beautiful country with some interesting things to see. May should be fine.

BRP “Commercialized”? YIKES! Then I can’t WAIT to ride the Trace. Looking forward to it after BMWROK Rally over Memorial Day. Nashville the middle of the week. BBQ ay Papa Turneys. I may not get home for a while. OH WELL!

Nice info going for a gander o the trace next week Picayune to Brown County Indi first medium ride since 1986. This info has extended my driving distance a few hundred miles should be worth it.