My first ride to Alaska in 2008 was a 15-day, 7,600-mile affair and the fulfillment of a long delayed dream. Yet I still had the nagging feeling of unfinished business. In many ways it merely stoked my appetite for northern travel.

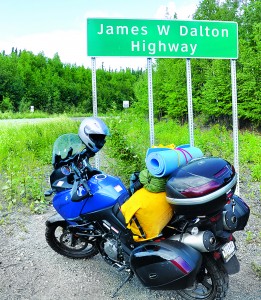

This time getting to Alaska involved a 21-day, 8,400-mile round trip from my home in Northwest Indiana through the prairieland of Western Canada, mountains of British Columbia and the Yukon. Instead of my trusty Suzuki Bandit 1250, I took a Suzuki V-Strom DL1000 that I purchased for this ride. A leftover 2007 model, it was shuffled from warehouse to warehouse until it ended up in my garage. One of its many attributes is the ability to accept knobby tires, since the main focus of this ride was the Dalton Highway, a road that is the overland lifeline of the oil fields at Prudhoe Bay. Along the way it crosses the vast Arctic wilderness, and is reputed to be one of the toughest routes in North America. From the time I learned of it, I knew I had to give it a shot.

The Dalton, or Haul Road as it is also known, was built for industry, by industry. As such, it was only open to general traffic to the halfway point until the mid-’90s. The entire length is now available to anyone wishing to give it a try. Not everyone should take the challenge, though, for it is not your garden-variety thoroughfare.

At 414 miles in length, the Dalton is about 75 percent gravel, or mud under the wrong conditions. The 175-mile segment to Coldfoot Camp, where I spent the first night, mimics any number of secondary roads in America and is fairly easy to negotiate on most any machine, at least when dry. At the Arctic Circle, Mile 115, all manner of bikes will be encountered. North of Coldfoot, signs warn of no services for the next 240 miles, and this is no joke. There is, however, a smooth, 22-mile ribbon of asphalt that seems oddly out of place. But soon enough the roads’ true character reveals itself. Teaming up with a narrow, soft-shouldered surface riddled in places with ruts and potholes, the Brooks Range stands sentry to anyone attempting to enter the North Slope and Arctic Plain, a land largely untamed except for the narrow Alaska Pipeline corridor.

I rolled into the muddy parking lot of Coldfoot Camp and scraped the slop off my boots. The place is aptly named. Gold prospectors in another century often turned back at this point. Many present-day riders do the same. The conversation with, or more accurately, lecture from highway veterans goes like this: “Conditions on this road change hourly. If you’re injured help will eventually respond from one of the pump stations or state highway maintenance facilities. Many times a helicopter ride to Fairbanks, or possibly Seattle, for treatment will be required, at a cost of $30,000 or more.” A tour bus driver chimed in, “But you might have to survive with your injuries for several hours until help does arrive.” And as the memorials I observed along the road testify, some don’t survive.

I headed out of Coldfoot under a gloomy sky, with light rain falling. When the short run of pavement ended, I was greeted by fairly smooth, graded gravel and dirt. The climb to Atigun Pass starts almost immediately; in the beginning, gradual, then at the pass itself, steep, with some 10 percent grades. Mud laced with calcium-chloride forms the surface, and it soon covered the Strom and me with thick, corrosive goo. At the summit I rode into heavy fog. On the descent, as if entering a different world, I was greeted by clearing skies and a stunning valley.

Upon leaving the shelter of the Brooks one arrives on the North Slope and eventually enters the vast Arctic Plain, a place of howling winds and an overpowering emptiness. The ocean lies about 150 miles distant. Flanking the Dalton to the east for the last 50 miles are the Franklin Bluffs. From there, a powerful gale pounded the bike and me, threatening to tear the tires’ tenuous grip from the road’s surface. Finally, at the end of the road is the prize: Prudhoe Bay, a grimy industrial camp and temporary home to about 5,500 workers in the summer and 1,000 or so more during the winter. Here these hardy souls produce 20 percent of America’s oil supply under some of the most challenging conditions on earth.

Riding to the end of the road in North America has become fairly popular. The half-dozen or so bikes I saw there were all adventure/dual-purpose machines: BMW GS, Kawasaki KLR and other V-Strom models. And all but one was fitted with some form of more aggressive tire, such as my Continental TKC 80s; its rider wished it was.

Once at Prudhoe, known officially as Deadhorse, it is not possible to ride to the Arctic Ocean, as access is tightly controlled by the oil companies. Instead, a bus tour of the facility ends with a ceremonial dip, after which it is prudent to book a hotel room to rest up for an early start the next “morning.” In mid-July the Arctic sun never sets. And that was almost my undoing.

Instead of securing a room, I headed south under the threat of rain at about 8 p.m. I wanted to put about 140 miles under my belt and camp at a primitive public facility, Galbraith Lake. However, the wind I hoped would be slightly less violent roared as if to punish my lack of respect. And the rain I sought to outrun began in earnest just as I left the relative safety of Prudhoe.

About 20 miles shy of my goal, I’d had enough of the wind, rain and fog. I knew I had to get off the road or I would become a Dalton statistic, another greenhorn done in by the road’s subtle viciousness. My refuge was a gravel pipeline access pad where I pitched my tent at Mile 119.

The next morning, I was up at 5 a.m. and ready to tackle the last 120 miles to Coldfoot. But first I had to cross the Brooks again. The rain was relatively light, but the fog was even heavier than on the previous evening, and it was impossible to see the moun- tain range less than 20 miles away. The valley I expected to signal the impending ascent never materialized, as it was shrouded in a thick mist. But soon a sensation of climbing was verified by my GPS, which had lost its bearings at the high latitude but could still judge elevation and speed. The reading of 3,000 feet told me I was fast approaching the pass, and it was time to pay attention. The sight of a group of trucks at a pullout should have alerted me to potential danger, but like a fool in his folly I pressed upward. I can only imagine what the truckers thought of my brashness; their CBs probably crackled with the news that another dummy was about to pack it in.

Fortunately, I encountered no other vehicles, and while I could barely see, I cleared the pass without incident. A feeling of accomplishment like I have never experienced overcame me, and I now believe I know why mountains are climbed, for I had scaled one, both symbolically and literally.

The Hot Spot Café, a fixture of the Dalton, is located about five miles north of the Yukon River. This oasis in the wilderness is a great place to grab some food and catch up on the latest road news. It was on my return visit that I learned timing is everything on the Haul Road—quite by accident I’d hit Atigun Pass at the optimum hour on the way up, and at one of the worst possible times of the day on my return.

One of my concerns prior to this ride was that the Dalton would become “civilized,” much as the Alaska Highway has, before I had a chance to tackle it. I am now convinced that this will never happen, particularly north of Coldfoot. As long as the oil flows from Prudhoe, America will always have a true wilderness road, ready for anyone wishing to accept the challenge.

Back where I started three days earlier, under the Dalton Highway sign, I affixed a sticker to the inside of the Strom’s trunk. It simply says, “I drove the Dalton Highway and survived.” And indeed I did.

(This article The Haul Road: A Motorcycle Tour of Alaska’s Dalton Highway was published in the April 2012 issue of Rider magazine.)

Did it on my FJR1300 july 2011.

John, I applaud you for making it up and back on the FJR. When I was in Alaska in 2008 on my Bandit 1250, I refused invitations to ride to the Circle, mostly because of the tires. Based on the conditions I encountered on my ride, I believe I made the right choice. But given enough determination, any bike and tire combo can make the run. You are proof of that.

It was quite challenging on the way up, lots of rain and mud:) Took me about 15 hours I think. I was running Michelin Pilot Road 2 tires. Not really ment for off road. I wrote a eBook and did a YouTube series on the trip.

I’m planning on making the trip the end of May or early June. I ride a “05 Gold Wing,i will be pulling a small trailer. I plan on running my regular Dunlop E3’s. Any suggestions or F.Y.I.”s would be greatly appreciated. Thanks

David, like I said in the story, all the bikes I saw at Prudhoe were adventure/dual-purpose models.Others have made the run of course, Dave Barr did it with no legs on a 72 Superglide! On the ride up, I did run into a guy at the Hot Spot who was on an older BMW K model sporting street rubber. However, he allowed that his run both directions was in completely dry conditions. On the way back, I passed a Harley bagger pulling a trailer just getting into some slick stuff; he was wallowing badly. I’ve often wondered if he, and his Goldwing trike mounted buddy were able to survive the much worse conditions they were about to encounter. Just be careful, and don’t hesitate to wait, or stop altogether if conditions are bad.

Fred

I appreciate the input. When I go, I will be in no hurry and have all the time in the world to wait out the weather.

A friend and I are planning this trip next summer, also from NW Indiana. Would love to talk to you some time about our trip planning, If you see a guy on a black Super Tenere wave me down.

Sure thing Ed, and since Super Teneres are kind of rare in beautiful NWI, I’ll pretty much figure it’s you. And I’d be glad to meet with you guys sometime. I’m from Valpo by the way, I’m in the early planning stage for a run up the Dempster Highway in the Yukon and Northwest Territories for 2013. I’m anxious to see how it compares with the Dalton. The pictures I’ve seen of the region are stunning.

I would like to get in touch with you, I will treat you to a coffee to pick your brain. If you can see me email shoot me and email.

That would be great Ed. But I don’t have your email address. You can send me one and we’ll set up a day and time.

I was nice to read your story. It remaind me of my trip tis year I maded to dead horse it was very difficult