by Perri Capell; photography by the author and Lynn Brown

We probably shouldn’t have lingered so long over lunch on the terrace of the little Italian restaurant in Sandpoint, Idaho, but if we had left sooner, we would have missed the black bear that ambled in front of our motorcycles a few hours later.

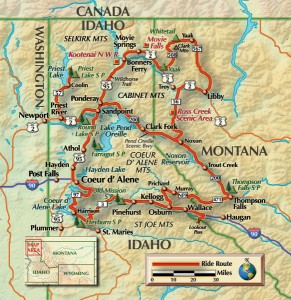

Boise in August can be unbearably hot (no pun intended). It didn’t take much to persuade my husband Lynn to take off a week and escort me around the northerly part of our home state of Idaho and the adjacent Cabinet Mountains Wilderness of Montana. North Idaho is called the Idaho Panhandle for its long and narrow north-south arm, but Lake Country might be better because so many crystal-clear lakes stud the region.

Their names are sometimes of French origin. There’s Lake Pend Oreille and Coeur d’Alene, and Priest and Spirit Lakes, to name a few. The more I heard about this lesser-known region just south of the Canadian border, the more I wanted to escape to its mountainous back roads in the heat of summer.

I arranged to ride a Suzuki Boulevard C50T, and asked Lynn to roll out the Suzuki GS1100 road bike that he had assembled out of the crate in 1982. It was fun to contrast the old and new roadsters, but I expected the gleaming 2007 Boulevard to attract the most attention. Instead, Lynn’s old tourer drew comments everywhere we went.

The day we saw the bear, we had reluctantly departed from Cavanaugh Bay Resort, a family friendly hotel on Priest Lake serving up great meals along with fantastic scenery. We had arrived there the day before, the first stop on our five-night trip. No one else was stirring that morning when owner Glenda Presley joined us under a thatched umbrella for breakfast on the deck overlooking Priest Lake.

A motorcycle community supporter, Glenda had treated us to a sunset boat cruise on the lake the previous evening, touring us around tiny islands poking their piney heads out of the serene waters. This 19-mile lake is spectacular, with forest descending to the shoreline and hardly a sign of humans to be seen from the water. As I gazed at the calm waters during breakfast, it seemed as though this piece of paradise belonged only to us.

After saying our good-byes, we retraced our steps south on ID 57 to Priest River and then east on U.S. 2 to Sandpoint. The latter highway follows the Pend Oreille River (pronounced Pon-da-ray), which serves as the drainage for Idaho’s largest lake, Lake Pend Oreille. Both are named after a native American tribe, also known as the Kalispels, who lived nearby. In French, the words mean “hangs from ears,” and refer to large shell earrings worn by tribe members.

Traffic was busy on this weekday morning, but the river views to the south were lovely. Bargain hunter that I am, I felt compelled to stop at a few antique and thrift stores, so it took us several hours to cover the 76 miles to Sandpoint. This town of 6,000 caters to tourists with an attractive downtown packed with shops and restaurants. Pay attention to the posted signs that say “Sandpoint Is a Walking Town.” Traffic stops as soon as a pedestrian puts a toe on a crosswalk, so watch out for vehicles making sudden stops in front of you—and pedestrians, of course.

Submarines in Idaho?

I didn’t believe it when someone told me the U.S. Navy tested submarines in Idaho during World War II. I mean, how dumb do you think I am? But it’s true. At 1,150 feet deep, Lake Pend Oreille is the fifth deepest lake in the United States and has acoustic properties similar to the open ocean, without its background noise. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, our Navy set up its second largest training ground in the United States on the lake’s south end at what is now Farragut State Park. Tests are still conducted at the lake on large-scale model submarine prototypes.

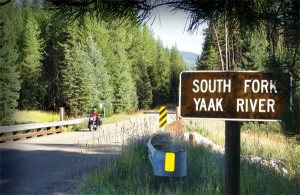

After lunch at that Italian bistro in Sandpoint, Lynn and I continued north on U.S. 95/2 to Bonners Ferry, traveling on what’s now called the International Selkirk Loop, a 280-mile scenic drive around the Selkirk Mountains into Canada and back. Our stretch of the loop also is named the Wild Horse Trail Scenic Byway after a traditional Indian route. We turned east when 2 split off toward Libby. About 20 miles later, just over the Idaho-Montana border, we made a left onto MT 508. Our destination was the Montana town of Yaak and a watering hole called The Dirty Shame.

Ascending 6,400-foot Clark Mountain, two-lane 508 is meant to be savored as it winds through leafy forests along the Yaak River. No cars, great scenery, a gorgeous waterfall—and bears. We were setting a leisurely pace when a hefty black bruin strolled out of the woods, casually glanced in our direction and then vanished into thickets on the other side of the road. Neither of us had time to get the kickstand down, much less pull out a camera, but I swear it was big.

It’s a Dirty Shame

Just shy of 30 miles later, we came upon Yaak—all two businesses of it. There’s just the Dirty Shame Saloon and Cabins and the Yaak Mercantile, both built of logs and across the road from each other. Around here, folks live off the land and disappear from the radar screen. The Dirty Shame serves great grub and drinks, and, as a nod to progress, laptop computers with Internet connections for checking email.

With more than 100 miles to go, we couldn’t linger. We took MT 567 south out of Yaak. For the Boulevard and this paved two-lane, it was love at first sight. During the next 30-plus mile stretch, I rolled on and off the throttle in continuous turns while descending the mountain to Libby. Shadows were lengthening, but sunlight still dappled the road through a canopy of pine and deciduous trees.

I wanted to turn around and ride it again, but this wasn’t the day. At MT 37, we pointed our bikes southwest toward Libby, rejoining U.S. 2. On the outskirts of Troy we took MT 56 south, enjoying more glorious scenery to the junction of 200, which runs along the Clark Fork River. It was time to head west to the Sandpoint Lodge, where we had reservations. The adjacent Landing Restaurant, where we had dinner, is understandably popular. The view of Lake Pend Oreille and Sandpoint’s twinkling lights is terrific, as is the summer berry pie dessert.

A Hooker with Heart

Miners flocked to the Idaho Panhandle after the discovery of gold and silver there in the late 1800s. The region’s old mining towns boomed, went bust and are now enjoying a revival as ski resort and tourist destinations. But when miners flooded the region, women followed. Today, I would learn about one of the most famous, Molly B’damn.

First we backtracked east from Sandpoint on 200, also called the Pend Oreille Scenic Byway. The Clark Fork River flowed alongside us to Montana’s Thompson Falls where we stopped for lunch. Then we followed signs pointing to Route 4, which led over 4,859-foot-high Thompson Pass to Murray.

In this former mining town (current population about 50), no souls were stirring. We parked our steeds outside the Spragpole Inn and headed inside, expecting to be the only paying customers. Instead, to our amazement, the bar was filled with a crowd of noisy senior citizens.

They had arrived by bus to visit the adjacent Spragpole Museum, an amazing shrine to local history created by the bar’s former owner. After Walt Almquist was given a few historic items to display in the bar, collecting mining and western memorabilia became his passion. He took over the vacant structure next door and then built room after room to house his collection.

Here I found Molly B’damn. Her story: Originally named Molly Hall, this Irish lass turned to prostitution following an unsuccessful marriage to a deadbeat husband. Her business name was Molly Burdan, and she relocated to Murray after gold was discovered there. When she said her name, locals thought she was saying Molly B’damn because of her Irish accent, and the name stuck. Molly had a heart of gold, saving the life of a woman stranded in snow at Thompson Pass and organizing Murray’s efforts to fight smallpox in 1886. When she died at age 35 of tuberculosis, there wasn’t a dry eye in town. The Spragpole Museum houses a replica of her bedroom.

From Murray, we pointed the bikes toward Prichard and then followed curves that seemed to fold under themselves on 496 south to Wallace. At Interstate 90, we rode west to Kellogg, a mining town now becoming a destination ski resort with the construction of a new hotel and restaurant complex at the base of Silver Mountain Ski Resort. The hotel suited our tastes, but we had one more stop to make. Dinner meant riding two-up in the lengthening shadows to the Enaville Snake Pit, a restaurant built in 1880 that has served as a bar, hotel, brothel, railroad stopover and starting-off point for miners. Fortunately, I didn’t have to eat snake.

The Trail of the Hiawatha

Passenger trains operated by the famed Milwaukee Road, which included four railroad lines, traveled through north Idaho to the Pacific Ocean for more than a century. The railroad went bankrupt in 1977, leaving the rail bed idle. After private and government interests raised funds, the rails were removed to create a mountain biking trail.

The path is now called the Trail of the Hiawatha after the company’s electrified high-speed trains that raced through at over 100 mph. Crossing seven high trestles and through 10 tunnels in just 15 miles, the trail is considered one of the premier rail-to-trail projects in the country.

We called ahead to reserve rental bicycles and then hightailed it 12 miles east on I-90 to Lookout Pass Ski Resort, the rail bed’s licensed operator. Besides mountain bikes and helmets, we rented flashlights, which came in handy during the ride through the 1.7-mile-long St. Paul Tunnel. It’s spooky and wet in there, but refreshingly cool during the dog days of summer.

Once out of the tunnel, the trail wanders through the Bitterroot Mountains. We enjoyed spectacular scenery crossing the high trestles and easy riding, since the trail is all downhill. An average 1.6 percent grade drops more than 1,000 feet during the trip, and at the end, shuttle buses return you to the parking lot.

By midafternoon we were back in Wallace, having lunch in one of its historic brick buildings. It’s fun to stroll around this mining town, which boasts antique shops, restaurants and even a bordello museum housed in a former brothel. Its claim to fame: Serving as the set for parts of Dante’s Peak, the film starring Pierce Brosnan.

Idaho’s Oldest Standing Building

No trip to the Panhandle is complete without visiting the oldest standing building in Idaho. The Old Mission at Cataldo, now a state park, was completed in 1853 under the supervision of Father Ravelli, an Italian-born Jesuit, using native materials and wattle-and-daub construction (a lattice of wood is covered with clay, sand and sometimes manure, then whitewashed). The priest designed the mission to resemble an Italian cathedral. Especially ingenious are the chandeliers and other lights, which were made of old tin cans, while the altar was faux-painted to resemble marble.

That afternoon, I followed Lynn south on ID 3, also called the Lake Coeur d’Alene Scenic Byway, around the southeast shore of the 30-mile-long lake. In the late afternoon we parked our bikes in Coeur d’Alene, the largest metropolis in the Panhandle with about 41,000 people. We would ride south to Boise the following day. Northern Idaho and Montana had been gracious hosts, allowing us to escape the heat on their back roads. I hated to leave.

|

|