story and photography by Mario Caruso

[This article about West Virginia motorcycle touring was originally published in the March 2008 issue of Rider]

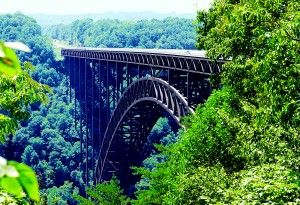

West Virginians love quoting New River Gorge Bridge statistics: the biggest steel span bridge in the Americas (used to be The World before the Chinese one-upped it three years ago), 3,030 feet long, 876 feet high, 1,700-foot arch span, 88,000,000 pounds and three years to build at a price of $37,000,000. Pretty impressive numbers and, sure, every tourist pulls off the highway, rounds up the pudgy herd and shoots a family photo at the edge of the big ol’ bridge. The amazing span also strikes a handsome pose on a few gazillion post cards and calendars.

But it wasn’t until we wound our way down the old, single-lane, Fayette Station Road to the bottom of the New River Gorge and looked up into the bridge’s massive, woven steel underbelly that I fully grasped what a beasty thing of beauty it is. On the way down we passed the bridge’s concrete feet, bigger than any house (or trailer) I’ve lived in. At the gorge bottom, standing on the restored 1898 bridge, even my wide-angle lens couldn’t capture the complete span, 90 stories overhead. The best part of this reflective moment is that all those camera-toting tourists from the highway lookout point jumped back in their mega-cages and roared off to the next Kodak moment, leaving just our motorcycles and us alone to explore the deep end.

You can’t blame them really. Chinked into the side of the rocky gorge, sections of the asphalt strip are not as wide as Mike and Millie’s suburban driveway. Motor mansion kamikaze mission.

This is what West Virginia motorcycle touring is all about. While western states strike riders dumb with sheer massiveness, West Virginia seduces with magically insignificant roads corkscrewing into intimate nowheres. The Mountain State’s peaks are not as grandiose as the Rockies or Sierras, but huddle so close together that getting anywhere requires squirming around their feet or scampering up their sides. Fifty-plus inches of annual precipitation hyper-feeds the dense hardwood forests rooted to their slopes. Almost no significant Civil War battles were ever fought in West Virginia, because by the time the soldiers climbed and hacked their way to a battlefield they were too tuckered out to do any fighting, if they could even find the enemy.

Not wanting to leave the bottom but needing to get back on our way we crossed the wooden planks of the old bridge and climbed the other side of the gorge to U.S. 19. The highway is a part of a large network of super highways dubbed the Robert C. Byrd Expressways after the eternal Senator who brought home the bacon to build them. They aren’t quite interstates, but pretty close. Oddly the broad swath these monsters cut through the dense forests makes them more panoramic than their smaller, forest-obscured brethren. A few miles south on this slab we exited into Fayetteville.

An old-timer gassing up his well-worn pickup gave us a brief Fayetteville history: historic coal town fallen on hard times until “outsiders” opened rafting, kayaking and canoeing outposts along the New River. “We weren’t smart enough to figure out that if you put a raft in the water someone would pay you to get in it!” Vintage storefronts along the main drag now house an assortment of fun and unique eateries, art galleries and creative shops.

Farther south we turned east and plodded through a series of semi-abandoned coal towns. West Virginia’s coal region is full of endless chains of painfully decaying old “company” towns groveling at the hem of the highway. They are quaint at first, depressing after the 50th one.

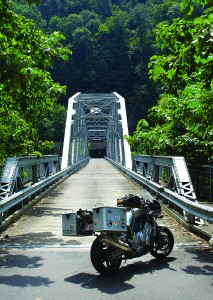

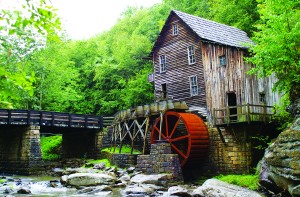

Past the hamlets on WV 41 we squirmed down a lovely set of twisties into a shallower section of the Gorge, crossed the river and twisted back up the other side. Little traffic bothered us as we cautiously zigzagged through thick hardwoods. West Virginia drivers fully grasp corner apexing, but have seriously bad aim and kick wads of gravel onto all those luscious right-handers. Off 41 we detoured into 4,100-acre Babcock State Park adjacent the river. A few hopeful fly-fishermen flicked at trout allegedly lurking in the fast-moving waters. We snapped the requisite tourist shot of the Old Grist Mill, which actually isn’t old but assembled from pieces of several mills of the 500 or so that used to work the river.

In the park a couple of local boys on 600 sportbikes recommended U.S. 60 East. Good call! We romped through several sporty miles before unwinding into a broad valley near Interstate 64, in itself not bad as it crosses the Greenbrier River, then slices through a narrow gap between Greenbrier Mountain and White Rock Mountain.

Our plan called for lunch at the famous Greenbrier Resort in White Sulphur Springs, where pilgrims have been “taking the waters” since 1778. The original 1858 hotel burned where the white-pillared 750-room, 1913 one now sits. We rode up the broad, landscaped entrance; past uniformed valets and bellhops unloading golf bags from Mercedes, and slinked back around to a fun little Civil War motif café in the old downtown.

Seven miles north of White Sulphur Springs WV 92 enters the Monongahela National Forest. Three miles later a small sign points west for County Road 16, Anthony Road. West Virginians call this a “layover” road. The only way oncoming cars can pass each other is if one “lays over” onto the shoulder. The canopied ribbon alternately follows, then climbs away from crystal-clear Anthony Creek, passing several Forestry Service campgrounds (and a few unofficial sites strewn with beer cans and garbage). A final drop to the Greenbrier River found us another campground tucked into dense forest at water’s edge. Kids quit splashing each other to watch us putt across the bridge.

Anthony Road dropped us onto U.S. 219, draped into the broad Greenbrier Valley. For the next 30 miles the two-lane highway alternates between meandering through pristine farm valleys and crooked climbing and falling over rocky nubs blocking the road’s direct progress.

Along this section of 219, Droop Mountain State Park commemorates one of the state’s few significant Civil War battles. The lookout tower gives a good view of the surroundings. A little farther north, three miles of CR 20 lead to Locust Creek Covered Bridge. Just off 219 we quickly toured author Pearl Buck’s birthplace, then turned down County Road 27 into 11,000-acre Watoga State Park. I was admiring Civilian Conservation Corps stonework and bridges accenting the roadside stream when a black bear crashed down the hill, loped past my face shield and jumped into the water. The bear and I stared wide-eyed at each other. I’ll clean my seat later.

In Marlinton we checked into the Old Clark Inn, a downtown Victorian mansion transformed into what owners Nelson and Andrea call a “Traditional American Inn.” The motorcycle magazines all over the parlor, covered motorcycle parking/ washing area, air compressor and helmet and gear hangers look pretty traditional, all right.

In the morning our innkeepers stuffed us with breakfast before we headed north for WV 66 and Snowshoe Mountain, West Virginia’s premier ski resort. Off 66, little County Road 3 climbs up to Snowshoe Village through some tight switchbacks and sports 180-degree views of surrounding peaks. “The village,” an instant community full of upscale condos and townhomes, makes me feel like Scotty beamed me to Vail or Aspen. We quietly slipped down the other side of the mountain back to WV 66.

Thick hardwood trees shade narrow 66’s drops, climbs and wiggles all the way to the old lumber and railroad town of Cass. Now a state park, you can ride an old locomotive, shop in the general store and stay in one of the restored railroad employee cabins lining the main drag.

North of Cass on WV 28/92 is an attraction from a completely different time, The Greenbank National Radio Astronomy Observatory. The Robert C. Byrd (him again) Green Bank Telescope is the world’s largest steerable radio telescope. The day’s tours were all booked so we pushed on.

WV 28 sways gently through a trough bordered on both sides by 3,000-4,000-foot forested ridges. Occasionally it threw a tight squiggle or two at us but in this area north/south routes are tame, east/west ones are wild. U.S. 33 is just such an east/west wonder as we climbed frantically up then down North Fork Mountain.

From U.S. 33, U.S. 220 scooted us along the bottom of another crease until we turned off onto one of the state’s great roads, CR 2, Smokehole Road. Only recently paved, this “layover road” hugs clear streams wedged between steep rock walls, then climbs and darts in and out of the rumpled side of North Fork Mountain. Feeble-looking guardrails separated us from painful drops. Through holes in the canopy we were treated to wide-angle shots of tight clusters of peaks blanketed with thick forest.

Too soon the road dead-ended and we veered west on WV 28/55. It was past our lunchtime when we saw Yokum’s Vacationland. Mom and Dad Yokum started the place in the ’40s with a couple of cabins on the river. Now there is a lodge, pool, horseback riding and Yokum Burgers, a big lean patty with plenty of “fixin’s.”

The highway slants southwest and soon craggy rock formations jutted straight up above the tree canopy. The rocks are part of a backbone formation of Tuscarora quartzite exposed over millions of years of erosion. The most imposing of them is Seneca Rocks, rising nearly 900 feet above the North Fork River below. We stopped at the National Park Service visitor center, caught the video and watched some climbers scale the rock faces.

From the visitor center we jumped on U.S. 33 West for another intense session of corner carving, this time over West Virginia’s tallest mountains, sometimes called the Allegheny Front or the Eastern Continental Divide.

Our final road, WV 32 took us through the broad, grassy Canaan Valley and on to Davis, the highest incorporated town in West Virginia and the size of a good sneeze. Another old coal/lumber town it, too, fell on hard times, but young outdoor enthusiasts and big-city refugees resurrected it and turned it and sister city Thomas into hip base camps for anything from skiing to mountain biking.

We set up camp at nearby Blackwater Falls State Park, then rode back to Susan Moore’s Bright Morning Inn. Talented Curtis Heishman prepares innovative masterpieces every weekend evening. For this evening he had collected five different kinds of wild mushrooms and artfully combined them into an exquisite pasta dish.

Then the fiends corrupted our wills with nasty desserts. What the heck, it’s the end of the ride—gimme the organic strawberry rhubarb pie!

|

|

Wonderful Job. Reading your article I’m stoked and ready to follow your trail. Really covered the great points that make the ride even more enjoyable. Thank you for taking the time.