It was a tolerable day, Kurt and I agreed, as we sat in the shade of a palapa on the sand at Bahia Concepción (Conception Bay). Air temp was in the low 90s, water temp at 84 degrees, a couple of puffy cumulus clouds in the light blue sky. Not a soul was to be seen, although a couple of motorhomes were parked a mile or so away on the curving beach, and a solitary sloop-rigged sailing boat lay quietly on the water.

A week before we had rolled across the border at Tijuana with the intent of finding out the limits of the two VStroms that Suzuki had been kind enough to let us borrow for a very pleasant 10 days.

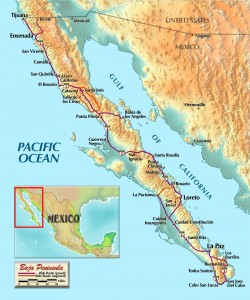

Neither of us had any interest in the northern tourist trapezoid, so we motored down past Ensenada, continuing on through the agricultural community of San Quintín, and then dropped off the bluffs down into the little town of El Rosario; we were approaching the real Baja, the old Baja.

Baja is a place of landscape and atmosphere. Away from the sea the scenery is starkly magnificent, rocks and cacti backdropped by harsh mountains, created, so the geologists say, some 70 million years ago. If you want to gaze on soft grassy meadows carpeted with spring flowers, birch and aspen trees, gentle rivers with fish jumping, welcoming motels and frequent gas stations, stay away from Baja. If, on the other hand, you like to avoid crowds, admire the more rugged aspects of Mama Natura, and revel in a remote campsite where the boojums dance under a full moon, then head south.

Away from the tourist zones, the atmosphere is sublime and the locals live each day to the fullest, worrying little about mañana. Tomorrow will come, no matter what, and if this silly American is hung up on a schedule, that is his problem, not ours.

We gassed up in El Rosario; one thing about the 225 miles between El Rosario and Guerrero Negro, is that gas stations might be closed, having no gas. That’s no real worry, as a number of Bajaneos earn a good living selling gasoline out of drums in the back of a pickup; and it is good gas, since locals buy it even more frequently than do tourists. I pack 5 feet of clear plastic tubing, just in case, which makes any passing vehicle a possible source of fuel.

The road crossed the wide, dry river on a long bridge and climbed up on a narrow ridge snaking south. The V-Stroms are great highway bikes, with superbly smooth power curves, excellent handling and comfortable ergonomics. Soon we were in the Valle de los Cirios, or Boojum Valley, as some call it. Lovely! The cirio cactus, reminiscent of the tapered candles (cirios) used by the Catholic church, can reach 40 feet in height and is found only in this 100-mile valley.

Coming into Cataviña we decided to try the dirt-roading capabilities of the V-Stroms. We immediately found the limits due to minimal ground clearance, as the 650, negotiating a very slow nadgery bit, came to an unexpectedly abrupt halt when the header pipe grounded. Then we got into soft sand, and found the front end to be too heavy in such going. Plowing through 50 feet of loose sand is doable, but long stretches can be quite unpleasant.

That night we were down at the Bahia de los Angeles (Bay of Los Angeles), and over a dinner of fresh fish done in garlic sauce we contemplated our possible routes. Kurt and I have traveled most roads in Baja, and they are loosely divided between good and bad. It has been noted that all good roads are more or less the same, while every bad road is different, which is very true of Baja. Also, you can ride a hundred miles of rough road, and then come to a 100-yard stretch that is impassable, which means you go back.

So we, being sensible fellows, decided to forgo the long stretches of bad roads, though every day we rode at least a few miles on dirt roads. We would stick mainly to the good roads, which all focus on that ribbon of asphalt that unwinds from Tijuana to Cabo. About 35 years ago the Mexican government decided that Baja could be a great destination for American tourists, if only there was a decent road. So they built one, with elaborate tourist services every hundred miles or so, offering clean gas stations, good food and a chain of hotels. The full 1,060 miles of Mex 1 was completed in 1973, and the Bajaneos waited for the inevitable flow of thousands of Americans who would leave dollars behind as they passed.

Unfortunately, or fortunately, depending on your point of view, this did not happen. The increase in traffic was small, and after 10 years a number of these tourist paradores were closed, the hotels sold to a private company, and life went back to its normal Mexican pace. The southern tip of Baja has become a major tourist resort, but 99 percent of the Americans who visit prefer to fly in two hours rather than drive in four days. Kurt and I felt we should sally south on the asphalt to see what progress had wrought.

With a few stops along the way, of course—Baja is chock-a-block with interesting places. Back in the mountains are cave paintings dating back 7,000 years or more, when the Baja climate was considerably milder and wetter. The Indians were hunter-gatherers who apparently enjoyed a pleasant life, having much free time on their hands with which to pursue artistic endeavors. I should add that the best rock-painting sites are very remote, requiring multiday trips on foot or burro.

In the late 17th century along came the Spanish, intent on civilizing the heathen. The padres decided that the best way to do this was to build large mission churches, the sheer size of which would impress these simple folk. Between 1697 and 1797, 35 missions and mission stations were constructed along the length of the peninsula, mostly by unpaid Indian labor. Many of these missions are in ruins, while some have been reconstructed.

The first one of real splendor is in the town square at the town of San Ignacio, easy to get to. The very first mission was built in 1697 at Loreto, on the Sea of Cortez, and has suffered fire and earthquake, but has been immaculately restored. In recent years the downtown of Loreto has been made quite pleasant, with pedestrian areas, and several nice hotels along the sea-front. West of Loreto, in the Sierra de la Giganta, is another very fine piece of religious architecture, the mission at San Javier. We had to traverse 25 miles of reasonably good dirt road to get there, and it was well worth the trip. However, a local told us that the back road continuing on to Ciudad Insurgentes and Mex 1 had a lot of sand; so we returned the way we came and took the pavement. Live to fight again another day and all that.

The 150 miles from Insurgentes to La Paz is mostly high and flat, featureless miles in any direction, until it drops down to the Bahia de la Paz (Bay of Peace). The city of La Paz is genuinely Mexican, and a stay is most recommended.

My preferred hotel is La Perla, right on the malecon (seawall), where the restaurant offers superb views of the bay, and of the strolling gentlefolk along the waterfront of a warm evening. The oldest part of the city is right behind the hotel, with the big marketplace and several museums, along with the cathedral.

If economy is in your mind, you might want to stay at the Hosteria del Convento, a block from the market, an old convent now transformed into lodging. For 140 pesos (about $13) you get your own private room, with toilet and shower, in one of the nuns’ cells. It is clean, quiet, and you may park your bike in the courtyard.

From La Paz the road down to Cabo can be done as a loop. We rolled along the east side, past the old mining town of El Triunfo, once the biggest town in Baja, now home to maybe 300 people. The road spins down into San Antonio and the Arroyo Agua Fria, and climbs back up to cruise along high country to the sport-fishing mecca of Los Barriles, and on to San José del Cabo. This city still has some old-world charm remaining along the Boulevard Mujares; it was the major town on the tip, until the developers decided it would be easier to focus on the fishing village of Cabo San Lucas. A string of beachfront resorts now runs 20 miles west from San José to San Lucas, varying in price and pomposity.

If you want to be near the Cabo “action,” the Hotel Hacienda Beach Resort is a good bet, where you can leave the bike safely and wander off to eat a hamburger at McDonald’s, or a taco at Taco Bell. If you need to do shopping, there is a Costco. No, there is not much Mexican about Cabo.

A different view can be seen taking Mex 19 back to La Paz via Todos Santos. All Saints (as it translates) is a small agricultural town a mile or so inland, where the American contingent has worked hard at turning the place into an “artists’ colony,” and the two communities appear to exist contentedly side by side, each profiting from the other. If you prefer not to stay in Cabo, the Hotel California in Todos Santos is a good alternative.

Now we were headed north, retracing much of our route. We trifled away a couple of nights at Bahia Concepción, and then suited up for the ride back to the border. The diligent can do the 640 miles in one long day, but we preferred a more leisurely two. A night in San Quintín, and then back into the USA via the Tecate crossing.

Baja California is really our backyard, easy to get to, easy to travel in. Great beaches, great tacos, great landscapes, great atmosphere. Take a trip there, and don’t rush.

(This article Taking Baja by V-Strom: Riding the length of the Mexican Peninsula on a Suzuki DL1000 and DL650 was published in the July 2005 issue of Rider magazine.)

You may also enjoy the two sidebars to this article:

V-Strom vs. V-Strom: DL1000 vs. DL650

Long-Term ’Strom: 15,000 miles on Suzuki’s adventure tourer (accessories)