Loss of cell phone signal along the way for some riders may equal stepping off the end of the earth, which they can physically do when they reach the end of this road. For others, reaching Deadhorse can equate to blissful hours of two-wheel solitude.

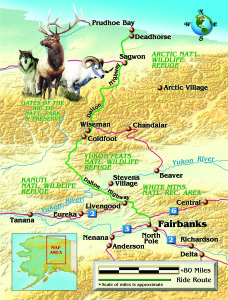

To intrepid motorcycle adventure-seekers and long-distance riders, tagging the farthest point north on the North American continent means a run up the Dalton Highway to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. Long known as one of America’s most remote and challenging roads, these 414 miles can humble those who think they, and their motorcycle’s manufacturer, know something about hard rides. For others, surviving extreme weather conditions, treacherous road surfaces, wild animals and “No Services” is the mental satisfaction with which they are rewarded for their preparedness.

The Dalton Highway was built to haul supplies to and from Prudhoe Bay after oil was discovered there in 1969. Constructed in 1974, its completion in five months was an engineering feat that balanced that of the parallel construction of the Alyeska Pipeline along which the road runs. The main wells and pumping station at Prudhoe Bay needed everything from people to pipe in a rush to solve an energy crisis and move the black gold from the Arctic Slope to the Alaska port of Valdez, 800 miles south.

Building the major section between the Yukon River, 140 miles from Fairbanks, and Prudhoe Bay, meant crossing not only the Arctic Circle, but also hundreds of miles of tundra that became a mud bog in summer and one of the coldest places in North America during the winter. Then there was having to traverse the Brooks Mountain Range and the Continental Divide while meeting rigid environmental requirements, compounded by the long distance from the security of an urban supply center.

The road was first known as the North Slope Haul Road because it was used to haul supplies to Prudhoe Bay, itself a pseudonym for what developed as a small town with the name Deadhorse. It now supports a population of 25 permanent residents and 3,500-5,000 part-timers, depending on oil pumping and construction. In 1981 the supply road was officially named the James W. Dalton Highway by the state of Alaska after an expert engineer in arctic construction. Deadhorse remained Deadhorse, but is often called Prudhoe Bay.

The highway was constructed by the Alyeska Pipeline contractor as a 28-foot-wide gravel road suitable for trucks. In places the base was built with 3-6 feet of gravel on top of plastic foam insulation over the frozen tundra to ensure a solid foundation that did not melt and sink when summer temperatures reach the high 80s south of the Brooks Range. Some grades of 10-12 percent were nightmares when icy or wet, more so in the winter when -80 degrees F was not unknown.

The highway was opened by the state in 1981 for public access only as far as Disaster Creek, 211 miles north from its start at the junction with the Elliott Highway. The road officially opened all the way to Deadhorse in 1995.

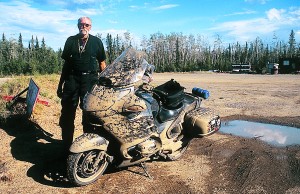

Today the Dalton Highway is 75 percent gravel and 25 percent paved, with an enforced speed limit of 50 mph. One published tourist guide recommends that drivers plan on two days each direction. On a good day an experienced motorcyclist can make the run one way in eight to nine hours. On a bad day the same motorcyclist can be found in a helicopter flying back to Fairbanks with broken body parts and his or her motorcycle behind a tow truck costing $1,200-$1,500, a too-often-heard-of experience.

In June of 2004 one group of motorcyclists each pitched in $150 to hire two trucks and a flatbed trailer to follow them up and back, then proceeded to fill each with crashed and broken bikes, and sent one rider home on an airplane. During one organized long-distance rally that awarded bonus points for tagging Deadhorse, a truck driver called over his CB to one entrant that “you guys been falling down all over up here.” The rider later said, “It can be really nasty when raining, and we were told we should take guns for protection from the bears.”

In early July 2003 a motorcyclist would ride through a raging forest fire the first 50 miles, then rain and swarms of mosquitoes at the Arctic Circle sign (115 miles from the beginning), and blowing snow over Atigun Pass (elevation 4,800 feet). When arriving at Deadhorse, tired, wet, cold and hungry, the rider would be told to keep an eye out for a grizzly bear that had been wandering through town!

In Deadhorse travelers find there are no public outhouses or tent-camping areas, that a private room at one of the two hotels (more like motels) can run $140, a buffet dinner $20 and that the road is closed to the Arctic Ocean. For a fee of $37 they can ride in a mini-van on an escorted tour for the final eight miles to the ocean where the stop is long enough to take a quick dip in the Arctic and join the Polar Bear Club.

On the upside of riding the Dalton Highway are the spectacular views, ranging from blue lakes to snow-capped mountains, sometimes sandwiching green trees or purple flowering fireweed and tundra in between. On June 21 there are 24 hours of sunlight to enjoy riding from the Arctic Circle and farther north, as this is the summer solstice and the sun does not fall below the horizon. Some motorcyclists ride up to Deadhorse from Fairbanks, fill their gas tanks at the 24-hour gas pump (credit cards only), then turn around and ride back down, all in the same day and in sunlight the entire time.

For the first-timer it is better to take a kinder, gentler and safer ride. The first 50 miles of the highway give the rider a pretty good taste of what to expect in road surface conditions, as the pavement stops and gravel starts. When dry, the oncoming 18-wheelers and cars can raise so much dust the road disappears. When wet, the surface can become as slick as ice on glass.

At the Yukon River crossing, 56 miles from the beginning (140 from Fairbanks), there is a gas station, motel, restaurant and visitor center. Four miles farther north is one of the motorcycling secrets of the Dalton Highway, the Hot Spot Café-Motel-Gas Pump (and tire repair shop). The small restaurant serves catcher-mitt size hamburgers, the owners are biker friendly and inside are numerous pictures of crashed cars and trucks on the Dalton.

Many motorcycle crashes here occur because riders find themselves slipping on the mud/loose gravel or weaving at speed in new, deep, soft road base, or dodging baby-head-sized rocks in construction zones. Another common mistake is to get too far on to the shoulder and into its soft gravel, which can suck the bike farther off the road and down the built-up embankment. One over-burdened Harley-Davidson rider remarked after taking four days up and back (and not falling), “I might have picked the wrong bike for this road.” The response was, “You might have picked the wrong road for that bike.” He said the 21-inch front wheel was wandering a foot either direction off-center at any speed above 20 mph, often trying to pull him down the right embankment.

A stop at the Arctic Circle sign where the road crosses the invisible global circle is worth a photo and has a primitive campground behind it. The posted warnings about bears and food should be heeded, and a healthy splash of mosquito repellant is recommended, whether tent-pitching for sleep or digitizing a memory.

At Coldfoot some motorcyclists call it quits to riding any farther north for the day. The town supposedly got its name in 1900 when gold prospectors got “cold feet” and went south before the harsh winter. Today Coldfoot has a modern visitor center, motel ($145 per room), post office, gas, pay phone, tire repair/welding shop and restaurant. Coldfoot also has the last gas/ food/services for the next 242 miles. While some motorcyclists get cold feet here, even in 80-degree summer, others climb off their parked and locked bikes and into a mini-van for a guided tour to the end of the road.

Five miles north of Coldfoot is a public campground (no showers), then nine miles farther the near-ghost town of Wiseman, once populated with over 100 people, now with less than a handful.

For the next 225 miles over the mystical Brooks Range and across the miles of rolling tundra, civilization is left behind. What you will see is the silver pipeline snaking in and out of the green trees (the last tree will be at the 235-mile point), then above and below ground. About the only other signs of humans, besides the road, will be the few pumping stations (closed to public access) and occasional pipeline maintenance vehicle, semi-truck (slow down and pull over, they have the size-right-of-way) or tourist. If you are lucky you may see caribou, muskox, Dall sheep and bears. The gravel road will occasionally change to 30-mile paved sections, and then you ride into Deadhorse.

The last 225 miles, as far north as you can ride on North America, can give the unprepared motorcyclist physical, mental or mechanical madness. For the seeker of proof they can manage themselves and their motorcycle, a successful ride up the Dalton Highway to Earth’s End is where they find a half-portion of their personal mental medicine. The other portion comes with the completion of the ride back down.

Do’s and Don’ts of the Dalton

• Lighten your load in Fairbanks. Store what you do not need and collect it when you return.

• Instead of purchasing an aftermarket extra-large gas tank, purchase a plastic gas container in Fairbanks ($5-$10) and strap it on the back of your bike. Remember to burn off what is in your tank to the level of what the plastic container holds, then stop and top off your tank leaving your plastic empty and light. Use the container for the long jumps between Coldfoot and Deadhorse, then donate it at the Hot Spot or Coldfoot on the way back down.

• Know how to repair a flat tire in the wild, and have the necessary tools/plugs/patches/tubes and air source to do it. Flat tires are common on the Dalton, as are large cuts in tires.

• Stop and clean your headlight of mud and dirt. Headlights are required to be On at all times and with only one, mud-covered, you might not be seen emerging from a cloud of dust by an oncoming vehicle.

• Slow down, especially approaching curves, crests of hills and any change in color of road composition.

• Slow down and ease to the right when any vehicle approaches you. Not only may they lose control (some are newbies and tourists like you) trying to pull over to make more room for you, but they can also throw rocks, mud and dust up for you to try to ride through.

• Do not stop on bridges, hills or in the middle of the road.

• Calcium chloride is used to keep the dust down on some gravel surfaces. Besides being very slippery when wet, it is extremely corrosive to metal and leather, and should be washed off as soon as possible after leaving the Dalton.

• When the highway is wet, stop and check the radiator as the mud will collect in it and restrict the flow of air and cooling.

• Have a Plan B for getting you or your bike off the Dalton and back down to Fairbanks. One BMW rider with a blown rear drive found that flying his bike by air cargo from Deadhorse to Anchorage was one-third the cost of having a tow truck with a trailer come up from Fairbanks and haul it back.

• Switch tires to knobbies or more aggressive dual-purpose types in Fairbanks or at the Hot Spot Café. Round trip from Fairbanks is about 1,000 miles and if the unpaved sections are wet, road tires can make for long, slow, dangerous days and nights. A few bucks for good traction is far cheaper than a tow or medical evacuation. If you are going to stay with your road tires, lower the air pressure.

• Much of the road is chip seal, which quickly eats up tires. Make sure you have good tread depth before starting, and remember a tire with lowered air pressure will wear faster. There are no motorcycle tires for sale between Fairbanks and the North Pole.

• Everything is expensive, and there is no ATM in Deadhorse. Cash is king, but credit cards work most places.

More Information

The Dalton Highway Visitor Guide, published by the Alaska Bureau of Land Management, (800) 437-7021 or (907) 474-2200; http://aurora.ak.blm.gov/dalton.

The Mile Post, ($25.95) from Morris Communications Corp., (800) 726-4707 or (706) 823-3558; www.themilepost.com.

Alaska By Motorcycle—How To Motorcycle to Alaska, ($19.95 plus $5 S/H MasterCard/ Visa) from Whole Earth Motorcycle Center,

(800) 532-5557 or (303) 733-8625.

Road Conditions-Alaska, Alaska Department of Transportation, (907) 456-7623 or (907) 451-2200; www.511.alaska.gov.

Road construction: (Summer Construction Advisories), Alaska Department of Transportation, Construction Dept., (907) 451-5466; www.dot.state.ak.us.

Author Frazier is a veteran of over 24 trips to and from Alaska and can remember “when we used to sneak up to Deadhorse on motorcycles before the road was open. Today the tour buses are more of a bother than the bears, which we seldom see.”

(This article The Road to Deadhorse was published in the January 2005 issue of Rider magazine.)