Traveling along the Usal Road, somewhere on Jackass Ridge, I half expected to meet a stagecoach pulled by four horses. Which was the basic conveyance 90 years ago, when this was the main route down the California coast. Much of my little trip was like experiencing a small movement in the fourth dimension, back in time.

Few people know about this unfrequented dirt road. Rolling north on Highway 1, Fort Bragg far behind, I stopped briefly at the Westport-Union Landing State Beach, and off in the slightly misty distance I could see Cape Vizcaino, and beyond that, Mistake Point. Then Highway 1 left the shore, wound through some low hills and into a small valley. Two hundred yards after a bridge crossing over Cottoneva Creek, a small dirt road, half-hidden by overgrown brambles, went off to the left. Many passers-by, flashing along at 60 mph or more, do not even know it is there.

A green CalTrans marker denoted this as Mendocino County Road 431, and another sign informed the reader that six miles ahead the road was not maintained in the winter months. This was November, at the southern entrance to the Lost Coast, which provides superb dual-purpose riding. The BMW R1150GS (“Gus”) and I began to scrabble up the slope.

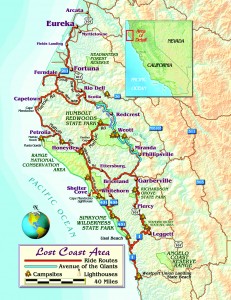

On California’s northern coast a 100-mile section is deservedly called the “Lost Coast” because it has few inhabitants, few roads, and, best of all, few tourists. The Sinkyone and Mattole Indians lived there quite happily for generations, hunting, fishing, gathering, and then came the Americans about 150 years ago, looking to farm and cut timber.

There is more than a touch of the romantic when the notion of a “lost coast” comes to mind, with images of great four-masted schooners wrecked on remote beaches, Victorian-era farmhouses tucked away in hidden valleys, bear scuttling and deer bounding away as the motorcycle approaches. All the many ships that were wrecked on this coast have been destroyed by time and weather, but the rest remains.

Usal Road climbed steadily uphill, and within a quarter-mile the ocean was visible down below. Those first six miles were in reasonably good shape, leading over the hills and down to the mouth of the Usal Creek, where lies a rustic state camping ground; one vehicle was in sight. Beyond the creek the road’s condition deteriorated as it skirted the Sinkyone Wilderness. It climbed up and down, with steep, sharp turns, underneath heavy forest cover, the surface of the road dappled with light and shade, making it hard to detect the subtle ruts.

Gus and I were averaging maybe 10 mph, the ocean only glimpsed through the trees; it was not easy going. After 27 miles we arrived at a small crossroads, with Bear Harbor Road (dirt) descending quickly to my left down 1,300 feet to Needle Rock and the old harbor, Chemise Mountain Road (dirt) going straight ahead to wind over the mountain and join up with Shelter Cove Road. A single lane of thin asphalt went off to my right, through the small community of Whitethorn and on to Garberville and U.S. 101. Darkness was descending; I went right to Garberville and a motel.

In the morning we headed back west toward Shelter Cove. The Lost Coast can be divided into three parts: To the south is the Sinkyone Wilderness State Park, in the middle is the King Range National Conservation Area, and to the north is Cape Mendocino. The eastern boundary is U.S. 101 and the parallel Avenue of the Giants (old 101) as they sweep along the Eel River, through the Humboldt Redwoods State Park, from Leggett north to Scotia. That road was not completed until 1920, and until then all wheeled traffic had to go via Usal Creek.

Most riders will skip the difficult Usal Road, as from Garberville a good 25-mile road, with a lot of twists and turns, runs west to Shelter Cove, the only community of size on the Lost Coast—which means roughly 250 full-time residents. Crossing over the last ridge on that road, I saw the ocean about three miles ahead and 2,000 feet down, an impressive drop. The sheltering cove itself is at the south end of the flat bluff-tops where the majority of the houses are, and for years was safe haven to a small fishing fleet that would come here in season…until federal regulations put paid to the commercial fishing business. A short landing strip was built back in the 1960s, hoping to attract wealthy sport fishermen, but that notion foundered. Now the place has several hundred vacation homes, a store, a few inns and restaurants, and the old Cape Mendocino lighthouse has been relocated here as a tourist attraction.

Back up on top of that last ridge, King Peak Road (dirt) goes north for a dozen miles to meet with the paved Wilder Ridge Road. I knew that while the first six miles were relatively easy, the second half turned into a corkscrew section requiring a lot of first-gear work on the tight corners. Not recommended after a rain, and 6 inches had recently fallen.

The easier way to get north was to keep going east on Shelter Cove Road, taking the Ettersburg Road turn-off on Telegraph Ridge. This was a rustic single lane of pavement leading down to French Creek and up to Wilder Ridge, where King Peak Road intersected. All well and good, but as Gus and I descended Wilder Ridge to Honeydew Creek, we came upon a short unpaved section in the steepest part, about half a mile long and having some eight sharp downhill bends. No problem on Gus, but I recommend that touring and sportbike riders have steady hands and clear consciences.

Down in the valley the road zipped up to the general store, post office and social center called Honeydew, on the bank of the Mattole River. To the right Mattole Road ran over Panther Gap (2,744 feet) and on through the redwood park to join U.S. 101 near Weott. Riding that curvy, narrow road through those gigantic trees will bring to mind the scene in Star Wars where the little flying craft are dodging through the redwoods; it pays to concentrate.

To the left the road headed for the coast along the Mattole River, where the bottomland makes good grazing for the cattle. Approaching the village of Petrolia a sign pointing to the left announced: Mattole Beach 5 Miles. Nothing there these days but black sand and picnic tables, but it once was a busy little port where the local timber and farm products were sent out. The industrious (not me) could hike down the beach for a few miles to see the old Punta Gorda lighthouse.

From Petrolia came the first California petroleum (!), in 1865. Oil seeps had been found in the area, and the heavy, viscous fluid was put in barrels, taken to the wharf at Mattole Beach and shipped down to San Francisco for use as lamp fuel. The town has a few houses, a post office, two churches for praying, two cafés for eating, drinking and carousing, and not much else.

The real treat was coming, as I rode up to Branstetter Ridge and then down to the ocean. There was the coast, five miles of sea and surf and rock and paved road—and lots of cattle behind fences; the ranchers obviously did not want them wandering into the sea. I really have no idea how this stretch remains lovely and vacant (one small house is at

the north end), but wonderful it is, and to be cherished.

The road ran almost to Cape Mendocino, then turned right and charged steeply uphill to the top of Cape Ridge, and down into the Bear River Valley. This byway is a delight for those who like the curves and twists, because it never goes straight. I came up to the next high point, where a sign indicated Bear River Ridge Road to the right, Ferndale six miles ahead. I went right.

The ridge road ran for about eight miles due east, the first couple being paved, the rest graded dirt. I was on top of the world, almost as good as being in an airplane—on a fine day there could be no better ride. Toward the end I was looking down, way down, onto the Eel River and Scotia, a lumbering town.

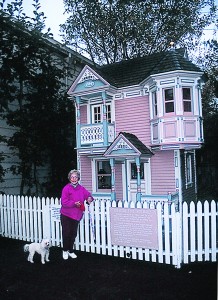

The road surface returned to pavement before descending precipitously down to Rio Dell, where I could skirt the valley of the Eel River and end up in Ferndale, a charmingly Victorian backwater—meant in the most positive of ways. It is a 19th-century agricultural town that slipped out of the developers’ sights in the 1950s, and thus has retained its original gracefulness.

From Ferndale it is less than 20 miles to the small city of Eureka, which offers everything from Cost Plus to many caffeine joints. And the Samoa Cook House, which provides way too much food.

Since I had to go back south I headed down U.S. 101, exiting at Pepperwood to go on the Avenue of the Giants, nearly 40 miles of redwooded bliss—except in summer when it suffers way too many motorhomes.

A real hack writer would say that the Lost Coast is a treasure to be found; I would say it is an excellent place to go ride a motorcycle. Especially a dual-purpose machine.

(This article The Lost Coast: Riding a Small Chunk of Northern California was published in the December 2004 issue of Rider magazine.)