It’s late May, a week before Memorial Day, and a new Honda Gold Wing is in the garage. There is perfect spring weather, the whole of California being cool and clear. I read a one-paragraph report in the paper that Tioga Pass, at 9,945 feet in the Sierra Nevada Range, has opened a week before expected. Shoot some passes, I say to myself—get out on the byways before the vacationing hordes clutter the roads.

Mountain roads are my idea of heaven on earth, the steeper and twistier the better. California’s highway engineers have been kind enough to put four of the best within a day’s ride of my house. The Wing is often thought of as strictly a highway machine, but it is equally competent on the byways. Despite its heft, it makes a pretty good pass-bagger, and is very comfortable on narrow roads that climb and turn sharply. Riding solo, with the rear suspension pumped up near max, nothing is going to scrape. If it does, just dial in a little more preload by pushing a button on the fairing.

I pack a few clothes for a couple of days, a tire repair kit, a rainsuit (never can tell), and the Wing and I are off. In the comparison test on page 34, the bike’s wet weight comes in at 905 pounds. Yet on an open road, nobody notices weight, and we sail across the San Joaquin Valley like a great land-yacht. I raise the windshield two notches to reduce the high-speed wind noise, set the cruise-control at 80 mph, and we are still getting overtaken on the interstate.

This is not a Gold-colored Wing, but what Honda calls “metallic magenta,” which can best be compared to ripe pinot-noir grapes. Since there is a great deal of bodywork on the bike, that means there is a great deal of color. But Honda has figured that the Wing nuts like bright, almost tropical hues, and flocks of yellow and orange and candy-red Wings can be seen at any rally.

I stop for lunch just as we enter the Sierra foothills, where the pavement goes from flat and straight to two-lane curves, and I drop the windshield back to its lowest position. With a wheelbase of 66.6 inches, the Wing steers more slowly than sport tourers in the sub-60-inch range, but that is no never-mind. On this bike we’re touring riders, not sporting types, and we just set up our corners in a more leisurely fashion. Most of us don’t even think about such things, as cornering has become such a natural way of life. When a wiggly piece of pavement stretches out in front, with half a dozen lefts and rights in quick succession, we do note that it takes just a bit of time to lean the GL from side to side. But I promise, the GL will go around any corner that a CBR600RR with its very short 54.7-inch wheelbase can—just a bit slower.

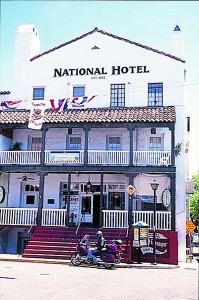

The California fields are already turning to gold as we cruise through Copperopolis and on to Mokelumne Hill and Jackson. Jackson was once a hell-raising mining town, with gambling and loose women even into the Eisenhower years, but it has since cleaned up its act in an effort to attract the family tourist. A 19th-century hotel, the National, is on Main Street, where I have a sarsaparilla at the bar and think about the men and women who came out to strike it rich. Some did, most didn’t.

Jackson sits 1,200 feet above the Pacific Ocean, and we get on Route 88 for an easy run up to the 8,573-foot Carson Pass—named for the frontier scout, Kit Carson, who came this way in the 1840s. Good views with lakes and forests and mountain vistas. Then we drop 3,000 feet down to Markleeville, which lies along the Carson River’s east fork. Out of Markleeville, Route 4 going west toward Ebbetts Pass is the most dramatic climb on these Sierra passes, and a commendation should be given to the workers who had the difficult job of laying that asphalt.

The Wing’s 100 lb-ft of torque shines on such a road. First gear is very low indeed, obviously designed to make an uphill start while hauling 500 pounds of rider, passenger and gear, as well as tow a trailer. I find second gear to be sufficient for most of these turns going up Ebbetts, since the torque curve starts at less than 2,000 rpm with 90 lb-ft of axle-turning power. That slightly oversquare flat six is an entirely impressive puller. Route 4 is getting very steep as it leaves Silver Creek and heads up to the pass at 8,730 feet. If you are Kansas born and bred, you might find the road intimidating, but as long as you remember that the throttle is your friend, you will have a marvelous time. Once over the pass the road goes through a mountain-top bowl, dropping down though Hermit Valley, past Mosquito Lake (lovely name), and back over the Pacific Grade Summit at a mere 8,050 feet.

The Grape Wing and I roll downhill for the next 35 miles to the resort town of Arnold, where friends have offered us a bed. Motorcyclists themselves, they have never seen a purple Wing (“… and never hope to see one, but from all that they have heard, they know that there must be one.” With apologies to Ogden Nash.) As the host opens a bottle of Wild Horse Merlot, I tune the sophisticated sound system to an FM station playing a Bach toccata and fugue, and we compare the subtle tints of the wine in crystal glasses to the evening sun refracting off the Wing’s paint. I have become accustomed to the color, and am rather enjoying it and its visibility; I think my friends are envious as they only have a dusty black Harley FXR.

Dawn to a perfect day, with the forecaster hinting at possible showers in the evening. I take the cutoff via Sheep Ranch Road down to Murphys, another old mining town changing over to winemaking and tourism. The western slope of the Sierras was dotted with mining camps after the Gold Rush of 1849; some grew into towns and survived, most disappeared after the strike gave out. Taking the Parrotts Ferry Road out of Murphys and across the New Melones Lake leads us to one of the best preserved of these old towns, Columbia. Now a state park, the place tries, rather successfully, to recreate the life of the late 19th century, with blacksmiths, stagecoaches and two old hotels which are still open to guests. A night at the Fallon is a good night, for future reference.

Wanting to avoid the traffic in the town of Sonora, the Wing and I take Big Hill Road out of Columbia, which will run into Route 108 near Twain Harte. When I look at my AAA map, red lines indicate the main roads, while thinner black ones show the interesting ways to get to where I want to go. Which is up to Sonora Pass at 9,624 feet; Columbia lies at 2,143 feet. It is one thing to cover this distance and altitude with a hundred horses on tap, but in 1852 the first wheeled vehicle came over the pass, probably pulled by four gasping mules. Back then, that was what one did; today, I look back and find the feat mind-boggling.

The west slope of the Sierras is generally quite gradual, and the 7,481-foot climb is rather easy. However, on the eastern side are great ramparts, from a distance seeming almost vertical, so getting down does require some good brakes. The GL1800A (for ABS) has right good ones. I can smell burning brake pads as I descend from Sonora, but that comes from a pickup with a camper on the back that was in front, before its driver found a place to pull over and let the stoppers cool off. The GL’s brakes are as good as they come, combining a linked braking system with an anti-lock braking system, providing excellent slowing and stopping ability under virtually all conditions.

After a precipitous drop down from Sonora Pass, Route 108 flattens out as it comes alongside the West Walker River, and terminates where it meets U.S. 395. We turn right and roll through the eastern valleys on toward Bridgeport. Seven miles beyond that little county seat we turn left onto CA 270, a 13-mile run to the ghost town of Bodie. Ten of these miles are easy pavement, the last three are graded but unpaved. The Purple Wing is a handful where the dirt is occasionally rutted or soft, but soldiers on without mishap.

Bodie is a genuine article out of the quasi-mythical Old West, booming in the early 1880s with more than 10,000 inhabitants, then going into decline as the gold played out, entirely abandoned when the Depression arrived. It has become a state park, but sensibly no real effort is being made to preserve the place, only to allow it to expire slow-ly and gracefully. The rangers’ duty is to prevent the tourists from hastening the demise of the town by taking home souvenirs. It is as good a ghost town as you will ever see, quite the opposite of Columbia—the two make a wonderful comparison, in fact.

I get to Lee Vining about 5 p.m., with the sun shining, Mono Lake glimmering in the late afternoon rays. I could run over Tioga—no, I’ll spend the night here, do it in the morning. To wake up at 6:30 a.m. and find it is raining, a serious all-day rain. I pack, pull on the rainsuit, and by 7 o’clock head the 12 miles up Route 120 to Tioga Pass. Lee Vining sits at 6,780 feet, Tioga at 9,945. Less than 3,200 feet straight up—piece of cake.

It is dark and gloomy and very wet as we go past the 7,000-foot sign. Soon I am dodging big rocks littering the road, washed down from the mountains by the rain. At 8,000 feet the rain turns to wet snow. At about 8,500 the snow is starting to accumulate on the road. A half-mile farther on the Wing skids and comes to a stop, upright, across the narrow two-lane road. Time to turn around…but there is no traction at the rear wheel, it just spins. Fortunately there is no traffic, and eventually I get the bike onto a shoulder where I can turn it around on the rough surface and head downhill, very, very slowly. Thick wet snow is on the windshield, the helmet face shield, my glasses. I am feeling rather foolish—I should have known better than to attempt this passage.

Back at Lee Vining the sky is black and wet all around. I figure my best bet is to go 200 miles south through the Owens Valley on U.S. 395, and head over Walker Pass on CA 178. The rain quits 50 miles down the road as we come into Bishop, but the next 100 miles have big winds and dust storms, and I am glad to have the big fairing protecting me.

Walker Pass is only 5,250 feet high. What a relief. Home for a late dinner.

(This article Three Passes, One Snowstorm was published in the October 2004 issue of Rider magazine.)

|

|