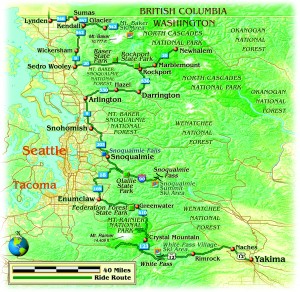

What do foreigners see when they look at America? If they’re headed east out of Vancouver on the TransCanada Highway around sunset, they see the shimmering dome of Mt. Baker, rising 10,777 feet above amber waves of grain. Awesome.

Ah, to see America—that’s one thing. To know it one really must visit Lynden, Washington, so Norman Rockwell perfect—as its citizens bicycle to and fro in the magic light—that I thought I’d slipped through the front cover of a Saturday Evening Post. But Lynden is real. Its pristine streets are walkable, but its buses are free, and so are its bicycles. You just register at the library. But alas there are no rooms for the night, and I’m tired. Maybe I did imagine it.

What I know of the Pacific Northwest is too little, having visited only once before, but I remember the Western Washington fair. It was in Puyallup, and I stumbled through its gates flat broke in 1979, riding a Ducati 750GT in sore need of repairs. I left the fair with a job no one else wanted—laboring in the scrap mill of Mr. Weyerhaeuser’s forest—which kept me off the streets for five weeks until I had enough money to move on. Back then there was no Pearl Jam, no Microsoft, no Starbucks. Who’d heard of latte?

But I remember Rainier Beer. rrrr (a little speck on the horizon) rrrAAAIeee (a dot growing visibly larger on the TV screen), nnnIEEEerrr (a quick, clean upshift to fourth) bEEE-errr. Was the bike in that commercial streaking toward the mountain or away from it? The image is foggy but the sound remains clear. Funny, that mountain was my daily companion for five weeks, yet I never once ascended her in that time.

Back across the Canadian border, not an hour’s ride from Lynden, I met a lad on a Kawasaki KZ400. I’d guess both he and his bike had passed 21-22 summers. He rode well, easily sluicing the underpowered twin past dozens of cars and a new 600 sportbike…despite the weight of his camping gear and a race-ready mountain bike which he carried on his back! Like me, he didn’t know where he was spending the night, but seemed much more buoyed by its possibilities. Never caught his name, but I vowed to be more like him.

If only I had the time. Mt. Rainier—Tahoma to the Nisqually and Puyallup Indians who first lived there—is the goal, but how can you just ride past Mt. Baker? You can’t. Not when the rest of the West is charbroiling in the August heat and an army of nine-year-olds is just itching for a snowball battle.

Gotcha!

Back down the mountain. Route 542 is a twisty bugger. Route 9 south is fast and swoopy. The guy on the new Honda CBR954RR seems surprised that he can’t shake the 700-pound ST1300. But that’s another story. Gotta get to Tahoma.

North Cascades National Park isn’t the most efficient way to get there, but lord, it’s a pretty ride along the swiftly flowing Skagit River. It’s late afternoon now. Through the arrow-straight conifers pass slender shafts of sunlight, like frames of a silent-movie reel. It’s a soothing syncopation—until the light crashes through where loggers have fractured the forest. But instead of crying out, the forest whispers back with new saplings and precious wildflowers. I’m reminded of Jonas Stamper, the failed homesteader in Sometimes a Great Notion, Ken Kesey’s epic tale of logging in the Pacific Northwest:

In between Washington’s prodigious National Forests (Mt. Baker, Snoqualmie, Okanogan, Wenatchee, Gifford Pinchot) and the commercial ports of Puget Sound lies a verdant but ephemeral farm belt. Southbound navigation is tricky here. Keep a steady rudder and you’ll glide through orchards and sunflower fields, past meadows where thoroughbred ponies romp beneath snowcapped peaks. Drift to the west and the urban tentacles of Interstate 5 will squeeze you into their smoggy clutches.

A sunset photo of Mt. Rainier was my goal, but now metro Seattle traffic (among the nation’s worst) is my reality. Still, my one memory of Rainier is that it is big. So I head west on Route 2, toward Stevens Pass, in hopes of sighting the great Tahoma. I did this road in reverse 23 years ago following a sleepless night along the railroad tracks in Wenatchee where the Ducati threw its chain. In the morning, after replacing the chain I discovered I only had two gears, enough to power me on one of the sweetest in a lifetime of memorable rides.

Alas, Route 2 between Snohomish and Monroe now quivers from the noise and fumes of metropolitan motion. Yet past the mall and the expressway, there it is—still 40 miles off as the crow flies but looking as if it’s on just the other side of the field.

“You must get a lot of people who stop to take photos here,” I comment to the owner of the fruit stand.

“No, not really,” she replies, surprised that I find her busy highway spot of interest. There’ll be a motel room down the road, I’m sure. I call it a ride and wait there in her field for the sun to cast its rays lower…lower. Right…there.

What a wonderful day. The town of Enumclaw is on my mind, a highway café where we’d meet for mugs of coffee and buckwheat cakes before rending the forest serenity with the acrid smell and angry bark of oversized Husqvarna two-strokes—chainsaws, that is. I used to leave Tacoma and head east on the Ducati in fog as thick and black as gearbox oil. Somehow, every day, on the same spot, climbing the same hill, just when I was convinced the sun would never shine again, Rainier would burst through the clouds, a golden stairway to heaven. I’m headed south this morning through unknown farm towns that could be in rural Illinois or Ohio—or I was, at least, until a construction detour spit me into the Seattle/Redmond/Bellevue morning rush hour. Maybe Interstate 90 is an escape? Perhaps another platinum view of the great one? The interstate is scenic and swoopy, and it’s ever so easy to forget it has a speed limit. By Snoqualmie Pass I’ve racked up 40 fast miles, and it’s clear there’ll be no Rainier sightings. No big deal. I exit and explore a teeny flume of a forest road which spirals downward through the firs to the South Fork of the Snoqualmie River. Descending the curves, I watch the ST’s “outside” thermometer climb 12 degrees.

In Enumclaw, when I stop for gas, nothing looks even vaguely familiar. Has the memory faded or simply been “malled” by the dozers of economic growth? A little saddened, I finish fueling and prepare to ride out of town when suddenly, through the gasoline vapors, wafts the sweet smell of memories I never knew I had. I look up and see the passing logging truck, loaded down with 20 tons of fresh-cut Douglas fir. Then another and another. On the road out of town I pass what looks to be the Old Highway Café. There’s a golf course next to it now. Ah well.

My job was one that no one wanted and only a few transients grudgingly took on, but the money was good. The chainsaws weren’t the puny toys of backyard tool sheds. They were motocross engines with four-foot blades that could kick back and split a man in two. So I kept my distance, content to do the grunt work—piling cut “rounds” of cedar in the sawdust. One Monday, when the Ducati and I finally had the means to hit the road, I just didn’t show up.

That was 23 years ago, but now I recognize the very dirt road where we used to enter the forest…and keep moving. I told you what those chainsaws can do.

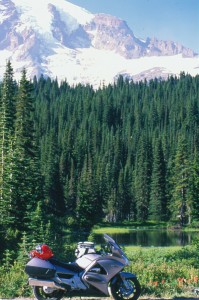

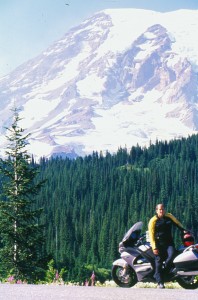

The beauty of Rainier and the Cascade range is that their flanks and forest floors are as magnificent as their summits. You can stop anywhere—anywhere—and marvel over some detail of their physiques, be it a cascading stream, a meadow of wildflowers or even the velvety moss and lichen stockings worn by the forest giants.

The route up to the Sunrise Visitors Center is steep and twisty—a great motorcycle road and not even that crowded on this midweek August day. When I gas it hard and slide on some pea gravel coming out of a hairpin turn, I realize how foolish I’d look tossing away a state-of-the-art touring bike while playing Ricky Racer on one of the nation’s natural treasures. The park speed limit is 35 mph, and there are more than a hundred miles of macadam capable of imparting pleasant riding sensations while showing proper reverence for one’s surroundings.

Among the mountain’s most popular attractions are the high alpine meadows where hardy perennials like Jacobs ladder, pussypaws and golden daisy replace the snowpack for a few short months in summer. In fact, it’s already looking more like fall in the meadows above Sunrise (elevation 6,400 feet). The subalpine or hemlock zone is pleasantly cool and still teeming with color: scarlet and magenta paintbrush, bluebells of Scotland, white mountain-heather. On the lightly beaten trails I enjoy equally the solitude and the occasional human encounter. Among those encounters is a birding guide from the island of Trinidad. He’s about my age, and this is the first time in his life that he’s laid eyes upon snow!

Covering all of the park’s roads is fairly easy. Getting out is another matter. To the south, forest fires are raging. To the north, there’s a madman threatening to shoot any motorist who crosses his path. I choose trial by fire, which turns out to be not so bad. A 10-minute queue enables me to worm my way to the front and enjoy an unmolested 47-mile gallop across White’s Pass. In classic tortoise/ hare fashion, all the vehicles—even the 30-year-old Peterbilt—catch me at the sub-sequent roadblock, in the Tieton River Canyon. The temperature here is 30 degrees higher than at Sunrise, and a roseate sky is settling over basalt cliffs wrapped in sage and cottonwood trees. To my eyes it looks more like Mexico than the Pacific Northwest, but as I said, I know too little of this part of the world.

The firemen give us the signal and one by one we file behind the guide truck. There’s a little sliver of a moon above the canyon, and on both sides the trees are ablaze. The mighty Honda has carried me through fire and ice in the same trip. In all honesty, I don’t think my beloved Duck would have made it.

|

|