Oh give me land, lots of land,

under starry skies above,

don’t fence me in.

Let me ride through the wide open country that I love,

don’t fence me in.

Cole Porter

Oh yes, but not on a slow nag. I’ll take that new Honda, the silver one with that gorgeous 103-horsepower flat-six engine that gives me the Porsche heebie-jeebies, and oh absolutely, the comparison is apt because what we have here is the potential for true spiritual recklessness, a luxotourer that thinks it’s a crotch rocket. Forget everything you’ve heard and read about Honda’s new GLl800 Gold Wing. Trust me, it’s better than that. And this sweet seamless machine is exactly what I needed at this tender moment in my life.

I wanted space, lots of it, preferably space in which I had never ridden before and so central Nevada was calling me like Circe herself. U.S. Highway 50 particularly, because its nickname is “The Loneliest Highway in America,” its storied history that of an old Pony Express and Overland Stage route, and 300 miles east of Reno at the Utah border it ends up in a place the name of which alone reduces my blood pressure, Great Basin National Park. I figured it was a good start.

Being without a girlfriend at the time I was planning this tour, I wondered if I would require female companionship. Moments later I called Melissa, my ex-girlfriend, with whom, miracles of miracles, friendship still exists. She agreed to go. Over a tuna sandwich at a coffee shop in Fallon, east of which begins a long ride on a long road where the next dot on the map, Austin, is a hundred miles away, I ask our young waitress about it.

“Oh, it’s just an old silver mining town, not much there. You want to see something special, try Virginia City.”

I say a polite thanks but think, oh yeah, Virginia City, wonderful Virginia City, real special, right in the heart of all that hideous megalopoloid gridlock that now extends south from Reno all the way down to the once bucolic little burgs of Minden and Gardnerville where strip malls and cluster housing and interminable traffic lights and hordes of SUVs have turned the pastures of heaven astride the Eastern Sierras into a shocking metastasis of suburban LA.

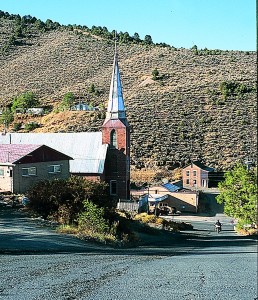

YEAH, LAND, give me lots of land, and it happens fast east of Fallon. The world opens up into a gigantic amphitheatre of sun and wind and sky, a vast oceanic expanse of land the scale of which is only accentuated by the clean line of Highway 50 disappearing ahead into a broad, two-mile high mural of the Clan Alpine and Desatoya Mountains. At the International Hotel (since 1863) in Austin, Heather, our waitress, implores us to order her grandmother’s walleye perch. “Skip the liver,” she says, “it makes me sick to cook it.” Walleye it is and, wow, it’s superb. So is this old town lost in time in a niche of the Toiyabe Range. It wasn’t so quiet when the mines were booming 140 years ago and 10,000 people showed up for their share of the $50,000,000 in silver.

But now, what a relief to wake up on a brilliant, 30-degree, sage-scented October morning at 6,600 feet with maybe a single rooster crowing. Nope, “not much there” except three of the finest pioneerera churches preserved in the west, and in fact an entire community that’s a rich and remote tableau of colorful history unfettered by a single sign of commercial overload.

I dislike making reservations. It has cost me a few times, but not many times, and in fact the no-plan method of motorcycle touring has more often led me to memorable discovery than any disappointment. But on this part of the map where the dots are few and far between, I deem it wise while we’re having lunch at the Silver State restaurant in Ely to call a motel in Baker, a very tiny dot 70 miles away on the edge of Great Basin National Park.

“Do you have a pay phone?” I ask our waitress.

“Where do you need to call?”

“Baker. I figure we better book a bed.”

“Oh, it’s OK to use our phone. It’s right over there by the register.”

Little things mean a lot, even though a good heart is no little thing.

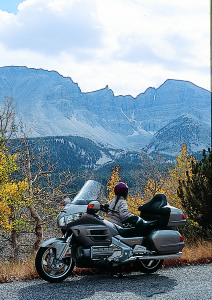

Great Basin National Park. For years I’ve wanted to ride here because (1) it’s the newest national park, having been so designated in 1986, (2) it’s the least visited, being remote as the moon, and (3) something attracted me about a place that represents the dominant physical feature of the western United States, I concluded weaving the Wing up the road in the park to 10,000 feet on an afternoon when a fresh 37-degree wind and a tumultuous sky carried the promise, the fragrance of an October storm. We parked the machine at an overlook and the desert floor, the dry bed of an ancient inland sea, an Ice Age lake of which the Great Salt Lake is just a remnant rain puddle, stretched so far into Utah that the horizon seemed to suggest the curvature of the earth.

Baker, Nevada. Population 75 but it seems more like 5. My kind of town. You can have Chicago, Frank, I like a town that’s no more than 50 yards long, a place, like the brochure says, “back of beyond where cell phones don’t work and the newspaper is a day late.” The Silver Jack Motel, tucked in a copse of trees ablaze with autumn, has seven rooms and when we check in six are vacant. Bill Rountree and his wife Katherine run the place.

Up the street at The Running Iron, a favored local watering hole, newly re-opened after being shuttered for a while, Arla, the bartender, says, “Have a beer. It’s on the house. We’re celebrating.”

Later, after the earlier promise of rain is being delivered, I see that Bill has considerately covered our motorcycle with a tarp.

Oh yeah, this is my kind of town all right, and my kind of people, too.

Veteran Rider contributor Dick Blom used to have a rule on the road, a rule besides the one that dictated he never met a speed limit he liked: Ahundred miles before breakfast. It’s a good rule, particularly when a fall morning breaks on the high desert with astonishing clarity after an overnight gale and the near-freezing air is as redolent as wild mint. Only problem is Melissa, despite my repeated instructions to come prepared for wind chill on this ride, doesn’t. By the time we pause back in Ely to refuel the Honda and our stomachs, she is not a happy camper (“I’m going to rent a car”). But being experienced in these matters, I solve the problem in time-honored fashion. We go shopping. Afiberfill vest and a few other assorted undergarments do the trick.

EGAN CANYON Pony Express Station.

Schellbourne, Nevada. July 16, 1860. An ad in a California newspaper at the time read: “Wanted. Young, skinny, wiry fellows. Not over 18. Must be expert riders. Willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred.” As we sip coffee here in October 2001, there’s a story written in the wind and we can read the words, these abridged from the journal of William F. “Billy” Fisher, whose first job at 20 was delivering the mail for a hundred bucks a month: “The only men at Egan Canyon Station were Mike Holten, station keeper and Wilson, a rider. The soldiers had left as we all supposed the Indian war was over. But about 80 of the renegade reds, who had fought under Leatherhead, in all their war paint, rode up to the station and demanded of the boys flour, bacon and sugar. The boys handed out the provisions knowing it would not do to refuse. Mike then started to gather the Express horses and put them in the stockade corral but one big Indian who could talk some English told him to go into the house, that the Indians would take care of the horses and them, too. Holten and Wilson were brave men, well armed, and expecting to be massacred, closed up the only door and window with grain sacks, leaving a few chink holes to shoot through, determined to sell their lives as dearly as possible.” Of course there’s more, an ending right out of a Hollywood script, but you want to ride out here and read it yourself, do you not? Of course you do.

While seated in a coffee shop in Elko on a late afternoon. I ask a couple of local men seated in an adjacent booth about Highway 225 which juts north of here for a couple of hundred miles through some country.

“Anywhere to stay in Mountain City?” I inquire.

“Maybe, if the hunters haven’t booked it up. And I wouldn’t be riding up there after dusk. Lots of deer, cows, too.”

We continue our northward trek. The low rolling hills and the ravines of the plains awash in gilded light and lengthening shadows, the immense sprawl of the natural world, seems to offer solace that all is not what we would like it to be all the time, and that perfection, at least our idea of it, isn’t even in the cards. An hour or so later, at Wild Horse Crossing, the temperature is hovering near freezing and despite the fact I’m wearing everything I own under my Hondaline riding suit, I begin to pray silently in my helmet: God up in heaven, please let there be a vacancy at the Mountain City Motel. Ah, 20 miles later just south of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation, answered prayers in what is quite literally the middle of nowhere, a place of pure nirvana. A toasty room, a hot meal. If Melissa is as happy as I am, she’s awfully quiet, which is hardly ever a good sign.

Mountain City, Nevada. Time, 7:55 a.m. Temperature, 16 degrees. A hundred miles before breakfast? I don’t think so. We linger two hours or so until ice crystals on the motorcycle melt, and then it’s off to Idaho, through the extreme southwest corner of the state where you can tell just by glancing at the map, that Highway 51 between the Nevada border and the small ranching community of Bruneau is “The Loneliest Highway in Idaho.” It seems that way until I miss a turn and end up in Mountain Home, a town going nuts with road construction, and there is brisk activity at the Air Force base since 9/11. After spending the better part of a week in the big empty, the traffic, the mall, the Wal-Mart, the tension, the reality in Mountain Home is overload. I can’t get out of there fast enough.

Back on course on Highway 78 tracing a verdant bank of the Snake River, the mood softens immediately. At least it does until I pause at a historical marker near Murphy citing the proximity of Silver City, a ghost town that was a booming l9th century mining nexus where a nearby diamond discovery turned out to be a hoax and sank a few banks.

Jordan Valley, Oregon. What a shame to only overnight in this remote frontier era outpost, this lonely place where little has changed since the old Star City stage rumbled through town loaded with gold and silver from Idaho mines on its way to a U.S. mint in San Francisco to help fund the Civil War; where Indian wars raged as the Paiute, Bannock and Shoshone tribes did their level best to recover treaty lands lost to white settlers; where Basque sheepherders emigrated in the 19th-century from the Pyrenees—they, too, seeking respite from what they regarded (and many still regard) as unjust hegemony over their ancient homeland; and not the least interesting historical footnote, where Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid camped one night in 1900 after robbing a bank in Winnemucca, Nevada.

For dinner, we choose The Old Basque Inn, a lovely cottage once the home of the local Madariaga family, located across the street from the fronton, a stone court built in 1915 for playing pelota, or Basque handball. The atmosphere inside exudes the warmth of an ancestral family home, but I couldn’t help but immediately notice a racket emanating from a large commercial refrigerator in the dining room, like the compressor was about to lose its shaft. I’m talking about galling and knocking that made conversation in a normal tone impossible. It stuns me to observe other people seated near us who seem oblivious or at least inured to what I regard as absolutely out of the question.

We order our meals. The lamb chops are fine. But I can’t resist querying a woman passing our table on her way to the door.

“Excuse me, were you not bothered by the noise in this room?”

“What noise?…(pauses as she hears the din)…oh yes, I see what you mean. …I guess it would be difficult to have an intimate conversation in here.”

Morning. What a morning. A ferocious high desert gale packing curtains of rain has lashed the area overnight, but it’s breaking up quickly as we arise. I wipe the Honda dry and off we go at 75 mph under a dramatic gunmetal sky breathing air that smells like cold licorice. To ride on such a morning is joy freighted with the notion that sometimes it’s great simply to be alive. I make a right turn at a historical marker posted on Highway 95 commemorating the gravesite of J.B. Charbonneau, Sacagawea’s son, who died of pneumonia in 1866 at the old Inskip Ranch where the fortified rock house still stands. I ride the machine three miles down a gravel road to the memorial where we pause for several minutes by an American flag snapping in a stiff wind on the infinite carpet of the plains under all that sky, as alone with each other as any two people could possibly be.

Little known to most Oregonians, let alone the rest of the world, the Owyhee River flows for more than 400 miles from its headwaters in remote mountain ranges in Nevada and Idaho to its confluence with the Snake River. It passes through only one town, Rome, Oregon (population 50), which looks to be the size of a postage stamp from atop a steep rise as we approach from the north a broad valley the Owyhee drains. While having breakfast here, we are told of the “grandest canyon in Oregon” just upstream, of a series of deep volcanic gorges, of some of the most spectacular riparian scenery in the northwest, and (key for a passionate fly fisherman like yours truly) of trophy small mouth bass. A return in the spring sounds like a fine idea.

IT’S DAY SIX as we ride back into Nevada and stop for fuel in the border town of McDermitt. Given the 6.7-gallon tank in the 1800, and its 32- to 34-mpg thirst quotient, range hasn’t been a problem out in the big empty, which could not be said of earlier models. The only complaints about this wonderful machine I can come up with are the side panels, the right one being necessary to remove for something as basic as checking the oil. Should be a snap, right? Well, it’s not. There’s way too much effort required to remove and replace it without swearing under your breath, but the good news is the motorcycle never used a drop.

Melissa needs to get back to work but there’s time to stall it off one more day. Down we go to Winnemucca for dinner at Ormachea’s, where I know from prior experience the lamb shanks are as good as those I once enjoyed in northern Spain in the old Basque capital of San Sebastian, and then there’s Winners Casino where we can throw the dice for a dollar a pop and either win a little or at least not get hurt too badly and have some fun in either case. Then, we’re homeward bound, northwest toward Bieber on Highway l40, an appropriate finale since the route cuts another swath through some of the most starkly beautiful, wide-open country left in the west. Atop a 6,000-foot summit, I pull the Wing into a viewpoint for another look at the high desert spread below us for as far as the eye can see. Someone once said it’s just damn good to know it’s there. Let’s toast to that.

(This article THE BIG EMPTY; Connecting The Dots was printed in the January 2003 issue of Rider Magazine.)