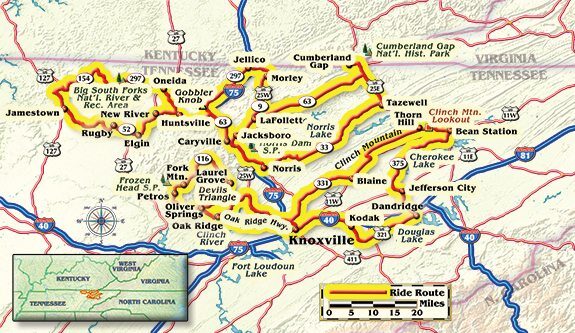

A sweeping 180-degree turn curved upward into the hills of Frozen Head State Park, and our guides, from the local Harley shop, were quite understanding. “I think yu’all ride a lil’ bit faster than us, so yu’all go on ahead and we’ll catch up at the next stop sign.” And off we went, three experienced motorcyclists chasing each other up to Armes Gap, a steep wall on one side, steep drop on the other, fog lines on the sides of the narrow road, two Harleys and a Triumph Thunderbird. Then we dropped swiftly down to the vanished mining town of Fork Mountain and the New River. This was the beginning of the Devil’s Triangle, and Satan could not have designed a more devious byway.

One good thing was having very little traffic on Tennessee Route 116 for the next 45 miles. Most of the little coal mines along the way closed long ago, and the pavement was pretty free of dirt from the few side roads. Some roughly patched sections could bring a little nervousness, with some bouncing over the bumpy bits, and a few truly gnarly switchbacks were evident, uphill and down. In the first section, I was leading on a new Harley Ultra Limited and kept hearing scraping sounds—but it wasn’t me, just the T-bird behind. This is the kind of ride that a curvy-road enthusiast will delight in, and can be ridden with abandon or conservatism. But should be ridden. And here is some advice: the bottom third of the triangle, from Laurel Grove to Petros, is not very exciting, so I would just turn around at Laurel Grove and go back those 45 miles.

All this joy was compliments of the Tennessee Department of Tourist Development, which had invited three moto-journalists to participate in this four-day affair. One March evening I flew into Knoxville, where I had been a couple of times before—Honda held its Hoot rally there for several years. I like the place, and despite the inevitable urban sprawl, if you can get a hotel downtown your feet can take you to interesting places. Our lodging was across the road from Market Square, the city’s center for evening activity, including Scruffy City Hall, with 40 beers on tap and entertainment every night. The Scruffy name came from 1982 when Knoxville hosted a World’s Fair and some misguided journalist called the city a bit “scruffy.”

This is on the western edge of the Appalachian Mountains, the Cumberland Highlands, which offer superb highway venues for any motorcyclist. The names of towns and villages are a pleasure in themselves, like Stinking Creek and Greasy Hollow, Frost Bottom and Lickskillett.

This used to be hardscrabble country, where a living was made with hard work, growing a couple of acres of tobacco or going into the coal mines. Not much money in tobacco anymore, and most mines have closed, with light industry and clerking in a mall taking over.

The real charm of riding in these parts is the nature of the terrain, the valleys, ridges and many rivers, with roads following the contours of the land. In 1933, the Roosevelt administration saw that this area had been hard hit by the Depression, and went on a job-making spree. Everybody wanted electricity, and hydro-electrics were a good way to go, so the Tennessee Valley Authority was created and dams began to go up. The first to be completed was the Norris Dam, blocking the Clinch River, which began sending out electricity in 1936.

Take a run over Clinch Mountain on U.S. Route 25E and at the top you’ll see the Lookout Restaurant…stop in for a piece of vinegar pie. Back when someone wanted to bake a lemon pie and lemons were scarce, apple cider vinegar would be substituted. This place still makes them fresh every day, and while the taste is interesting I’d have to say I prefer the lemon variety.

Anyone touring in the Knoxville area should go to the “Secret City,” as Oak Ridge has been called; it did not even appear on any map until 1946. This is where the Manhattan Project to build the atomic bomb began in 1942 and ended with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. In the space of a few months, the U.S. government appropriated 60,000 wooded and farmland acres and built homes and laboratories for 75,000 people, including scientists and their families. The place still researches nuclear energy, and restrictions are still in effect, so we had to leave the bikes and take a van around the place to see how the Atomic Age has progressed in the last 70 years.

After two nights in Knoxville, we moved to the small town of Caryville alongside U.S. Route 25W and Interstate 75. The owner of our motel, Hack Ayers, told me the story of his pa, John, being shot by revenue agents. Story goes that the police showed up and John wasn’t home, but they found some illegal whiskey in the barn. And while they waited for John, they sampled the stuff. When John got back, everyone was a little too gun-happy and John got shot through the heart; the leather jacket he was wearing, with bullet hole, is on display in the motel. Hack did not seem to hold a grudge.

Making whiskey without paying taxes has been a tradition in this part of the country ever since the government decided that a tax on liquor would be profitable. And making moonshine, or white lightning, was not necessarily a small-time business, as in 1973 when revenuers found a 15,000-gallon still under a barn in nearby Dandridge. The 1957 movie Thunder Road romanticized the notion, and probably most roads in Tennessee have been used by drivers in hotted-up cars, ready to put the pedal to the metal should a police car appear in their rearview mirror. Such cheerful shenanigans led to organized stock-car racing and NASCAR.

Apparently, if you pay the taxes, you can now sell moonshine—sometimes referred to as white whiskey. Moon Pie Moonshine was available in the store, and we took a small bottle back to the motel for a midnight sampling. Part of my cultural research for the story.

We had new guides in Caryville, a couple of local boys, one of them a deputy mayor. And they did know the backroads, as we whisked along narrow pavement instead of along the newer highways. On the first day out of Caryville we rode up to Rugby, a curious exercise in real estate promotions in the late 19th century. An English utopianist, Thomas Hughes, thought he had a solution to the inherent problems in the British nobility’s attachment to primogeniture—in which the eldest son inherits everything, leaving second, third, etc., to look for a career in the army or the church. Hughes bought a lot of wooded land, and in 1880 began advertising it in the British press, getting a few hundred jobless aristocrats to come over. Soon a Victorian town appeared, with some 65 buildings, including an Episcopal church and a large library. However, the notion did not last and by 1900 the place had pretty much disappeared. Some 60 years later the few buildings that remained were restored and the place has become one of the nation’s official historic districts.

We were riding along many, many miles of two-lane road running through endless forests. The area is noted for its trees—mainly pine, hickory and oak—and a minor lumber industry. The establishment of a national recreation area, Big South Fork, just north of Rugby, protects thousands of acres. The park is more receptive to hiking and boating than riding. But one ribbon of asphalt does cut across the middle, Leatherwood Ford Road (State Route 297), very much worth the trip as it drops down to cross the Big South Fork Cumberland River.

On the second day we rode up along State Route 63, part of the White Lightning Trail, to Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, right where Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia come together at Cumberland Mountain. We were at the west end of the trail, known as the Wilderness Road, the first passage across the southern Appalachian Mountains. Around 1775, a property developer hired a competent woodsman, Daniel Boone, to figure out a way to get people and livestock, and eventually wagons, over the mountains and to the fertile lands beyond. In the 30 years after he blazed a way, some 300,000 Americans followed that road, and undoubtedly made that developer rich. An Interstate tunnel now funnels all the traffic under the mountain, and the old Wilderness Road is now for hiking. However, after we had a looksee at the museum, we took the road up to Pinnacle Overlook—this was not many miles, but twistier than a corkscrew, I promise you. Great views.

Then it was time to catch a plane and go home. A couple more days and I could have done the nearby Tail of the Dragon and then gone up to Shady Valley and ridden The Snake, both of which I’ve been on before. Now I have done the Devil’s Triangle and completed the Tennessee Trifecta. And I’m glad that Satan didn’t get me.

PS: Anyone wanting a copy of The Long & Winding Road, the Tennessee touring brochure for motorcyclists complete with maps, can run up easttnvacations.com or call Molly Gilbert at (865) 209-1820.

(This article The Devil, Moonshine and Motorcycles was published in the November 2014 issue of Rider magazine.)