Reprinted with permission from Honda’s Red Rider magazine

People today often complain the age of adventure is dead, that there are no more frontiers left to explore. Emilio Scotto proved them wrong … by riding his Gold Wing (the Black Princess) 485,000 miles in 10 years, visiting 232 countries, islands, colonies, atolls and non-independent countries, which represents close to 99 percent of the land mass in the world.

Scotto, a native of Buenos Aires, Argentina, had dreamed of traveling around the world since his childhood. He bought his first motorcycle, a new 1,100cc Honda Gold Wing Interstate, in 1980, and logged about 30,000 miles on the bike over the next four years. In 1984 he quit his job and sold all his belongings to fund his travels. This netted him all of $306. He had no sponsors, no credit cards, no contacts. He had never even traveled outside Argentina. But one way or another, he was going to ride around the world.

The trip began on a discouraging note. In January of 1985, as Scotto arrived at his first border crossing—from the eastern border of Argentina into Uruguay—the Uruguayan border official laughed out loud at the sight of his heavily laden GL1100. “Going around the world, are you?” the official said. “With all that you’re carrying, you look like you have enough gear to ride around the universe.”

Scotto rode through Uruguay and on to Brazil and the glamorous city of Rio de Janeiro—where he was promptly robbed. He had just enough resources left to travel 600 miles north to Salvador Bahia, where he landed, flat broke. By chance, he struck up a friendship with a young man who happened to be from a wealthy family, and Scotto was soon headed northward once again.

North and east he rode, battling through huge storms until he arrived at the Amazon, the world’s densest jungle. There, he was told the jungle was impassable by vehicle, and that he must return to Argentina and begin his journey up South America along the Pan-American Highway, on the west coast—a detour of 8,000 miles. Undeterred, Scotto located an ancient river-going vessel to carry him and his Gold Wing up the Amazon River to Manaus, Brazil.

“Besides my Gold Wing and myself, the boat carried maybe three dozen rough-looking characters,” Scotto recalls. “As I watched and listened to them, it became clear that these people were outlaws, people living on the fringe of society.” Many were bandits or criminals who the authorities would not bother as long as they remained in the jungle. One night some of them started a card game. A man who Scotto took to be their leader warned him not to play, but when a seat opened up at the table, Scotto was invited rather forcefully to take it. “On the table was money and gold as currency, plus weapons—guns and knives. This was not a social game,” he says.

To his amazement Scotto won five straight hands. The other players grumbled that he must be cheating, and a gun was drawn. Scotto offered to return his winnings, which infuriated the others even more. “So, now you insult us, too?” one player shouted. “You might not live long enough to step on shore again.” Scotto spent a sleepless night, and was relieved when at sunrise the boat docked at Manaus. His companions of the previous night disembarked, winking and grinning at him, then their leader handed Scotto a crumpled scrap of paper. On it were written messages wishing him well in his journey.

“Do you understand now?” the leader asked. “They let you win so they could help finance your trip. These men are animals, but they wanted to help you continue your journeys—and also have a little fun with you. All of us wish you well. You see, by helping you, if you make it all the way around the world, we go around with you—even though we can never leave the jungle.”

In Nicaragua, torn by civil war, Scotto rode past a bullet-riddled sign that said “Sleeping Policeman, 500 Yards.” Sleeping policeman turned out to be the local term for speed bumps, two of which sent Scotto and his speeding Gold Wing airborne. As he slowed to a halt to catch his breath, gunfire erupted and bullets sprayed the pavement all around him. Soldiers emerged from the brush and accused him of being a CIA agent spying for the Contras. He convinced them he was simply an Argentine tourist, and eventually they let him go.

The kindness of strangers often amazed Scotto. In Honduras he got a flat rear tire in the middle of nowhere. He removed the wheel by the fading daylight and was settling in for a long night when two peasants appeared out of the gloom. They offered to take the wheel to their village to have it repaired. Some time after midnight they returned with the wheel and the repaired tire, asked if he needed anything else, and refused payment for their trouble. “It was a favor. You don’t pay for favors,” one said, and directed him to a guest house where he could get some sleep.

Crossing the border between Mexico and Arizona, Scotto was immediately struck by the friendliness of the border guards, the cleanliness of America, the marvelous condition of the highways—and the low speed limits. In California he got eight speeding tickets, seven more than he gotin 400,000-plus miles of riding outside the USA. He went to San Francisco, Las Vegas, the Grand Canyon, New Orleans and Disney World, dodging tornadoes and lightning storms. He pulled into New York City flat broke, and took a job in a deli. A local TV station did a segment on his around-the-world quest, and the host made an appeal for donations to help him on his way. Enough people sent him money that he was soon on his way to Europe.

In 1987, after visiting the countries of Western Europe, Scotto penetrated the Iron Curtain. In contrast to the wealth of the United States and Europe, the poverty of communist nations shocked him.“Romania was by far the worst, most pathetic country I had ever visited,” he says. “It was an extremely poor country, but even worse, there was nothing to buy and nowhere to make purchases—no food markets, no restaurants, no markets at all. There were no hotels, so by sheer luck I met an embassy official from Cameroon who took me to a place in Romania’s capital, Bucharest, where I could rent a room for a few days.”

The lone, often broke traveler acutely felt his own freedom in contrast to the peasants gathering wood for fuel and carrying the huge stacks on their backs. “In my whole time there, I never had a single conversation with anyone. They were all afraid to speak.”

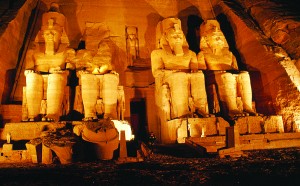

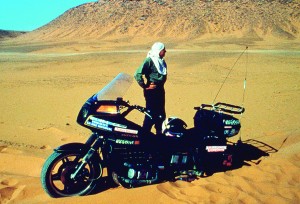

That freedom took Scotto next to Africa, where his goal was to visit all 55 countries. He arrived in North Africa at the port of Tunis to find himself surrounded by an ocean of sand—the Sahara. He pointed his Gold Wing toward the heart of it on a hard, dry, stony track unmarked by signs. The heat was unbearable, the sand kept getting deeper. He thought several times about turning back—and then things got really bad.

A sirocco—the classic desert sandstorm—descended upon him, pelting him with sand like rain from a monsoon. A gust of wind knocked him off the bike and tore the visor off his helmet. He huddled against his bike curled up with his head between his knees and struggled to breathe. Then, as suddenly as it began, the storm was over. His bike was buried, its chrome stripped off by the wind-driven sand, the aluminum polished clean. The storm had lasted only four hours. Some siroccos last for days.

Reaching the Atlantic coast of Africa at last, Scotto was forced to take a road dotted with enormous potholes. “These oval craters were at least 10 feet long and 3 or 4 feet wide. Each was filled with a substance that might have been water at some time, but had been reduced to a supremely smelly, primeval soup, covered with a dry, brownishgreen scum.”

In the jungles he saw “just green —dark green, light green, emerald green, olive green, blackish green, pale green, bluish green, greenish green, every imaginable shade of green. And it was hot, with a heat that never diminished, and a dampness that irritated, exhausted and crushed. Even the ever-furious, ever-hungry mosquitoes had drowned as it rained and rained. I was riding in vegetable soup.”

He almost became people soup during a harrowing encounter in a village where the stench of rotting flesh assaulted his senses. As he was led into a hut and handed a bowl full of some unknown liquid, he recalled the words of a friend in Senegal, who had warned, “Be careful, Emilio. In some parts of Africa they still practice cannibalism. They snare their victims with a drugged drink.” During his struggle to escape, some of the drink splashed into his mouth. He began coughing uncontrollably and ran for his bike, speeding away even as hands clutched at his shirt.

In Africa, Scotto, recalls, “I had encountered a million unexpected things—new lands, deadly situations, new rules, new beliefs, new realities, children starving, armies fighting, human sacrifices, cannibalism and more. I emerged from Africa a bit scarred but definitely battle-hardened, yet I knew something was missing from my life.” That something was love. He had left a girlfriend behind in Argentina, and when he reached the border between Turkey and Iran, he phoned her. Monica joined him in India, and they were married in New Delhi.

Monica brought another pair of eyes to Scotto’s journey, and a new perspective. At rest stops, for example, she sought a degree of privacy that Scotto had long since abandoned. It took her a while to get used to locals gathering around to stare at her as she emerged from the bushes. “They meant no harm,” Scotto says, “but they also had no grasp of a westerner’s sense of privacy. While Monica was mortified, I couldn’t stop laughing.”

The Indian people impressed the newlyweds with their kindness and consideration. “We never had a single confrontation the entire time. In fact, everywhere we stopped, people went out of their way to be kind to this curious pair of motorcycling foreigners.” In stark contrast to the friendliness of the people was the deadliness of the traffic. “There appeared to be no traffic laws, stoplights or crosswalks, no sense of yielding to traffic, no right of way. These drivers didn’t even seem to understand common sense rules. At one point, Monica and I decided to track the odometer, watching to see how long we could go without seeing an accident. Longest distance, two miles.”

In Bangladesh the Gold Wing’s driveshaft gears stripped. A friendly trucker offered to transport the bike and riders to the capital city of Dhaka. After unloading the truck’s cargo of bags of potatoes, it took 20 people to lift the Wing into the truck, after which the potatoes were reloaded. The tower of spuds caused the truck to list 45 degrees to one side, which didn’t deter the driver from maintaining a breakneck pace as Monica rode in the cab with three other men and Scotto clung to the running board.

Eventually Scotto learned why the driver was willing to take him and Monica and the bike along for free. They came upon a seemingly endless line of trucks waiting by the side of the road, and drove to the front of the line, to a river crossing. “In Bangladesh, the law gives foreigners priority travel status,” Scotto says, “so we went right to the head of the line for the ferry. Our driver had saved four or five days of waiting, and we gained a free ride to Dhaka.”

Busted flat in Dhaka, Scotto and Monica were offered a free room in a luxury hotel.Tourists were so scarce at the time in that part of the world that the manager of the hotel called a press conference. Restaurants fed the travelers for free, and people invited them into their homes to stay or visit. Honda of Bangladesh repaired the bike for free, and Scotto and Monica eventually said their farewells and headed for Southeast Asia, Australia and the islands of the South Pacific.

In Australia, while speeding through the Simpson Desert near Ayers Rock at 75 mph, an emu appeared seemingly out of nowhere and collided with the bike, tearing off a saddlebag and leaving its beak imbedded in the battery. Later Scotto blazed a route he called Blue Route 1, which he took to visit all the islands scattered around the Pacific Ocean, going from one island to the next on cargo boats, small aircraft, motorboats or whatever was available.

On Nauru, Scotto discovered the world’s smallest republic—only 8.4 square miles in total area, and getting smaller every day thanks to intensive phosphate mining whittling away the island’s core. He was the 69th tourist, and the first Argentinean, ever to visit Tuvalu, and his Gold Wing was the first motorcycle to touch wheels on its soil. Due to the lack of hotels, he rented a room in a private home, and one night was served dinner by the First Lady of Tuvalu.

At the Honda plant in Japan, the staff of HRC rebuilt the Gold Wing, refurbishing the cams, heads, carbs, fork, brakes and the exhaust system, and rewelding the frame. The euphoria he felt upon leaving Japan was quickly squashed when Chinese border officials told him he must pay a total of $70,000 to enter the country. Scotto contacted the Motorcycle Club of Beijing which, in turn, referred him to the president of the Beijing 2000 Olympics committee. “As a sign of goodwill and support for all sports, I was allowed to tour China freely,” he says, “with no restrictions, no supervision, an arrangement simply unheard of. More important, I could change money freely, just as if I were a Chinese citizen instead of a tourist—a privilege that gave me great leverage with the little money I had.”

He became the first outsider to tour Mongolia in 75 years, crossed the Gobi Desert on his way to the capital , Ulan Bator, and rode along the Great Wall for a thousand miles. Arriving at the border with the Soviet Union, Scotto discovered there was no longer any such thing as the Soviet Union—the Iron Curtain had fallen. The newly independent Kazakhstan was not admitting foreigners, and the Chinese told Scotto that if he tried to enter and failed, he could not return to China. Lacking a visa, he was exiled to a halfmile-wide strip of land between the two countries where he remained for two days without food or water until a Chinese TV crew arrived to interview him about his journey. The sympathetic crew pulled some strings, and Scotto was allowed back into China on the condition that he backtrack 4,000 miles to Beijing to0 get a visa from the Russian embassy allowing him to enter Kazakhstan.

Scotto found the former Soviet Union now ruled by thugs and gangsters, with living conditions worse than under the communists. Eventually he made it to Spain, where one of his sponsors, an oil company, asked him to test a special new synthetic oil in severe cold-weather running—in Iceland. There he put knobbies on his Wing and discovered one of the bike’s limitations—it was too heavy to ride in snow.

In Greenland he dined on raw whale meat and what he says was the worst-tasting dish in the world, raw monk seal meat. He roamed the United States and Mexico again, and received the VIP treatment in Cuba. Next, he touched wheels on 27 Caribbean islands and Guyana, where he visited the prison cell occupied by Papillon. After Suriname and the Galapagos Islands, Scotto made his way through Bolivia and Chile, and finally home to Argentina, where he got the last traffic ticket of the trip.

“After 10 years, two months and 19 days, my journey was complete,” Scotto says. “In those 10 years, I had packed in 100 years’ worth of experiences. I turned off the ignition and looked at my faithful motorcycle.We were now truly citizens of the world.”

Many thanks to Honda’s Red Rider magazine for allowing us to condense and reprint this story from its five-part series.

[slideshow auto=”off” thumbs=”on”]EMILIO’S JOURNEY BY THE NUMBERS

Emilio Scotto holds the Guinness World Record for the longest ever journey by a motorcycle, covering over 485,000 miles and 232 countries and territories, from January 17, 1985, to April 2, 1995.

• Two consecutive circumnavigations of the world

• 10 years, two months and 19 days on the road

• Six continents, including 232 countries, in 485,000 miles

• One replacement engine

• 12,500 gallons of gasoline

• 300 gallons of oil

• 11 passports of 64 pages each, when pasted together, stretch more than 6 feet in length

• 86 tires

• 12 batteries

• 9 seats

• Imprisoned six times (once in the USA, five times in Africa)

• 15 traffic fines (13 in California, one in New York and one in Argentina, on the day of his homecoming)

• Robbed five times (Brazil, Mexico City, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya, China)

• Target of gunfire two times

• Two traffic accidents (Yugoslavia, Tanzania)

• Nine collisions (with a man, a taxi, a deer, an eagle, a baboon, a pig, an emu, two dogs and innumerable insects)

• One major earthquake, two tornadoes, four hurricanes

• Three major illnesses, including malaria

• 90,000 photographs

(This article WINGING AROUND THE WORLD: EMILIO SCOTTO’S EPIC JOURNEY was published in the August 2004 issue of Rider magazine.)

This is great!!!!!!

Is there a book written on his ride around the world? How to source an edition?

book The Longest Ride by Emilio Scotto

What happened to Monica?

están juntos hasta el día de hoy