story and photography by Jerry Smith

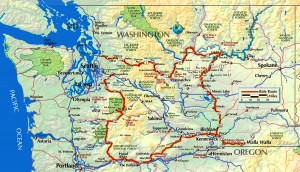

The state of Washington’s tourism board had this idea. Invite a group of motojournalists to ride around and report back to their readers about what a beautiful place Washington is to ride. They invited me, representing Rider, Buzz Buzzelli, editor of American Rider, and four others, one of whom never showed up. That guy should be kicking himself around the block right about now.

We gathered east of Seattle to pick up rented bikes. I scored a Honda Gold Wing, as black as sin and just as much fun. Buzz got a Harley-Davidson Road King, Andy from Motorcycle Escape a BMW, Niek from the Dutch magazine Promotor a Yamaha FJR1300, and Jim, a freelancer of no fixed affiliation, drew the low card, a Honda Magna with its best days barely visible in the mirrors. Tom, our guide, rode his own Yamaha FZ6. We saddled up at oh-dark-thirty and headed east.

We rode in a pack past fields and houses shrouded in a wet, late-September fog. Those who hadn’t started out in wet-weather gear wished they had. We followed Highway 2 toward Stevens Pass, past towns with names like Sultan, Startup and Index. The fog cleared as we rode higher, and the sun shone down on rugged mountains clad in fiery fall colors. Construction zones were marked with signs that said “Motorcyclists Use Extreme Caution.” Well, of course we do.

Group-think bit the dust early on. At Coles Corner Buzz, who prefers to ride alone and shun the beaten path for the road less traveled, went straight when the rest of us went left. Stops for photography soon splintered the rest of the group. As the day warmed up I stopped at a small store in Plain to take the liner out of my jacket. A friendly dog visited with two locals relaxing in plastic chairs out front. “Nice dog,” said one.

“Her mother was a beauty,” said the other. “Bob felt real bad when he dropped that tree on ’er.” “Last year on my birthday I hit a dog with my truck.” Plain’s a tough town

for dogs.

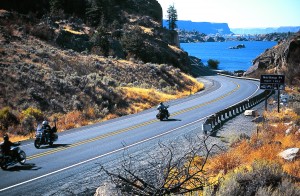

I missed the lunch rendezvous in Leavenworth. This was concurrent with discovering I’d lost the route map Tom had given out at breakfast. I rode on a bit farther to Wenatchee where I got a sandwich at a supermarket deli and ate it in the shade of a canopy covering stacks of cases of soda pop. From there I steered the Wing north along the west bank of the Columbia. On my side of the river, sheer rocky cliffs came almost to the shoulder of the road and shot straight up. Across the river the bank was wider, with crops planted right up to the base of the cliffs on that side. Where it wasn’t irrigated the land had the look of high desert. Take away the water and that’s what it would have been—and had been, not that long ago.

Our first night’s lodging was in Chelan, at the south end of the long, narrow lake by the same name. Even this late in the year the resort town was hopping. I sat on the balcony of my room making notes and enjoying the cool breeze off the lake as a speedboat scraped a white wake across the water in the distance.

Day two was a long one, with Walla Walla, just six miles from the Oregon border, at the other end. The group did the tourist bit at an overlook above Grand Coulee Dam and then, exhausted by the effort, Buzz, Andy, Niek and I stopped a few miles later in Electric City for a coffee break. At Pepper Jack’s we debated weighty issues like “Working hard, or hardly working?” in the way that only a group of writers on an expense account can, which is to say over several cups of coffee and slices of pie. It wasn’t entirely our fault. The waitress was so much fun we hated to leave.

Our first sight of Banks Lake banished any regrets. Start with the towering mesas of Utah’s Monument Valley, then fetch a river from Alaska with its deep blue-green water, and lay it at their feet. Niek, from low, flat Holland, was stunned by the stark beauty. “I could spend two weeks here just taking pictures,” he said. For the next 50 miles we spent as much time gripping cameras as we did turning throttles. At that rate we really would have been there for two weeks.

We found Tom and Jim waiting for us at the appointed lunch spot in Moses Lake. From our lakeside table we watched jet airliners and huge military transport planes landing and taking off from an airfield in the distance. As experienced motojournalists, all of us were used to clomping into fancy restaurants in our riding gear and covering empty tables with sweaty, bug-stained helmets. The same could not be said for the locals, who eyed us warily. It was here I decided to go on an all-salmon diet for the rest of the trip. These people might be a long way from the ocean, but they knew how to cook fish.

After lunch—and there’s no way to sugar-coat this so we don’t sound like such a bunch of dopes—we got lost. It was around this time I reminded Buzz to never again kid me about riding with a GPS. A paper map will tell you where you want to go, but it won’t tell you where you are, which is exactly what we needed to know. All the roads looked the same, as did the fields and low hills. The only things that changed were the signs pointing to tiny towns that weren’t on the maps we had. The towns had funny-sounding names that sounded vaguely Indian. For all we knew they translated to “Aren’t we going in circles?” and “We’re all going to die here.”

Then, on a no-name road in the middle of nowhere, by what I can only assume was the dumbest luck possible, we spotted Tom riding toward us. “Follow me,” he said, and we did, like chicks trailing behind a mother hen, all the way to Walla Walla.

The next morning Niek and I had tire issues to deal with. The Weather Channel had been tracking a front moving our way from the northwest that had the potential to make the last two days of our ride soggy ones. I wasn’t confident there was enough tread left on the Gold Wing’s front tire to cope with rain, and Niek felt the same about the rear tire on his FJR. After breakfast I made some calls and found tires for both of us at USA Honda, a 15-minute ride from our hotel. Brian told us to bring our bikes over as soon as we could, and he’d see to it that they were up on lifts right away. He was as good as his word. We were on the road by noon.

Several hours behind the others, Niek and I lost even more time to confusing road signs in Pasco. After a stop for directions we resumed our ride east toward the towns of Prosser, Mabton, and eventually southeast across the brown and rolling Horse Heaven Hills to that day’s scheduled lunch stop in Bickleton. We had already eaten, but stopped there anyway for a rest and some photos. Minutes after we pulled up in front of the Bluebird Café about a dozen bikes, all Triumphs, rolled up behind us.

It was a group on a guided tour out of British Columbia. Niek and I sat and talked with a couple from the Midlands in England as the tiny café filled with the smell of sweat-stained black leather and Cordura nylon, and someone punched up about five dollars’ worth of insanely loud rock music on the jukebox. The tour group was very international, and varied greatly in age and background. They were unanimous on one thing—they were having a blast. They’d left British Columbia several days earlier and were headed for San Francisco. Two of them had put diesel in their Triumphs by mistake, and even they were having a ball riding in the chase truck towing their ailing bikes.

Niek and I reluctantly took our leave and continued southwest toward what was probably the oddest stop on the ride. High atop a bluff on the north bank of the Columbia River near Maryhill is the Stonehenge Memorial, erected by a man named Sam Hill to honor the memory of local soldiers who died in the First World War. It’s not an exact replica of the original in England, but more like what one might have looked like when it was new, right out of the box. The setting is dusty, bare and wind-whipped, and made me think not only about war and its consequences, but how much dirt I’d be coughing up later that evening.

We spent the night in a resort in North Bonneville. In the morning the Weather Channel gave us the bad news. Rain, and lots of it, right where we were headed—the Windy Ridge Viewpoint, which in good weather offers a harrowing close-up view of the aftermath of Mount St. Helens’ most recent tantrum, followed by the Paradise Inn, more than 5,000 feet up the side of Mount Rainier. The low, sullen clouds started leaking an hour into the ride. By lunch in Randle I was soaked from my neck to my knees, but very glad to be on the Wing with its barn-door fairing and wide windscreen. By about halfway up Mount Rainier I’d have traded it for a canoe. It was the first rain on the mountain for months, and it was making up for it all at once. Trees fell, mud slid, streams overflowed their banks. The raindrops sounded like buckshot on my helmet. By the time we floated into the parking lot of the Inn, all the roads on the mountain had been closed.

The road crews worked through the night to re-open them, and in the morning we upped anchor and sloshed down the mountain in a steady, heavy rain that occasionally let up just long enough to fool us into thinking the worst was over before opening up on us again. Rain means no photos, but take my word for it, the volcano region is spectacular. I’d been there years ago and always wanted to come back, just not under these circumstances.

By midday we were all so cold and wet there was no point in worrying about it anymore, and we started enjoying the ride again. We stopped for wonderfully greasy cheeseburgers at a place in Greenwater where Niek, through a slip of the tongue during a conversation about low-light photography, earned himself the unfortunate nickname The Flashing Dutchman. Lucky for him the ride was almost over, or we’d have worn that joke down to the cord. The rain slacked off, then stopped. After a final photo op at Snoqualmie Falls, we returned the rental bikes and were driven to a hotel by the airport from which we’d all depart in the morning.

So, how good an idea was it for the Washington tourism people to invite a bunch of motojournalists to ride around the state? It’s been weeks since I got home, and I still have this mental picture of rolling hills and deep blue water and the wide Columbia that I can’t get out of my head. Sometimes I swear the wind is laden with the scent of golden grasslands, or the murmur of a rocky stream. In the distance I imagine the dim outline of a conical mountain through the fog, or what looks like a farmhouse shrouded in morning mist.

If you ask me, it was a great idea.