About 50 million years ago, Africa, which was probably glancing down at its iPhone, crashed headfirst into Europe, which was just sitting in plate-tectonic traffic, minding its own business.

Like the hood of a crash-test Mercedes, neither Europe nor Africa were ever the same. A big chunk of Africa wound up on the top of the Matterhorn. Which is great for bargain-hunting climbers who want to conquer two continents for the price of one. But for us riders, the important thing is that this global fender-bender created the Alps. For people who prefer riding in curved lines, there is no better place on earth.

I am not the first to realize this. My friend Werner Wachter, the father of Edelweiss Bike Travel and my personal choice for Most Interesting Man in the World, Non-Fiction Division, started his empire based on a simple thought experiment.

Riding is great.

The Alps are great.

Why are you still sitting there?

When you are flying, the ground is usually below you—unless you are flying into Innsbruck. I found myself looking up at the white, broken-glass peak of the Hafelekarspitze as we dive-bombed into the airport. Herr Wachter is officially retired from day-to-day duties at Edelweiss, which gives him time to do silly things like pick me up at the airport.

I met our touring group that evening at the Hotel Kayser, just up the road from Edelweiss headquarters. We would have three guides: the legendary Christian Preining, who raced the Isle of Man on a CBR1000RR; Andreas Fetzer, a young German supermoto rider; and the lovely Angela de Haan, who could probably have given Christian a good race on the Isle herself.

Not a race

Christian briefed the group. We would be free to go wherever we wanted—just show up at the designated hotel each night or call one of the guides. Or just bring your bike back in 10 days. There would be two guided riding groups most days—a shorter route and a longer one.

“Remember,” said Christian, looking at the throttle hands twitching all around him. “This is not a race.”

At 9 a.m. the next morning we headed southwest toward St. Moritz. I had a new BMW F 800 GS Adventure test bike, which seemed about perfect: tall, well-damped suspension, strong brakes, smooth power, a comfortable seat and a proper sit-up riding stance.

As we sliced over the Stelvio Pass, my fear of being stuck in the middle of a slower group evaporated. Andreas, pursued by young Texan Scott Jansen, was going like Stinkenblitzen over fast, bumpy asphalt, with granite posts for guardrails and thousand-foot drops. Why did I insist on keeping up? For the same reason I rode a bicycle through our garage door in 1965, I imagine.

Not far behind me were Scott’s father, Joe, 73, and their buddy, Soup Campbell, 72. “Jeez”, I thought. “Am I supposed to be going this fast when I’m 73?”

That night, at dinner in Pontresina, Switzerland, Christian reviewed the day. “Remember when you said this was not a race?” I asked. He nodded. “You were right,” I said. “It’s not a race. It’s qualifying.”

Germatalian? Italideutsch?

On Day 2 we wiggled to the west, through an outcrop of Italy and back into Switzerland. When I take my final trip through here—hopefully a long time from now—I may still be able to ride. But I will probably have no idea what country I’m in. The Swiss/Italian border looks like one of those black firework snakes I used to light in our backyard. The official language of Switzerland is that there is no official language. Italians in Italy’s Sudtirol speak German. Even the place names are problematic. Are we on the Passo dello Stelvio? No, this is the Stilfserjoch. Which are the same thing.

We veered south toward Lake Como, then back up the Splügenpass, a road that winds up the face of a sheer granite cliff. Left onto the treeless Passo del San Bernardino, where the houses look the same as they did 5,000 years ago, rugged piles of stone with people inside. We trolled through Andermatt, Switzerland, where four passes—the Furka, the St. Gotthard, the Oberalp and the Susten—run into each other.

This far from nothing

After all these switchbacks, I was starting to learn to ride. I figured we were going through a new corner about every four seconds. That’s 7,200 corners in an eight-hour day. Even if you cut that in half to account for stops and straights, in seven riding days we would go through about 25,000 corners.

Christian, who is also a BMW Riding Academy instructor, advised staying to the far right on the narrow passes. He held his hands about eight inches apart. “You should be this far from the cliff or the guardrail. Or—if it’s just a drop-off—this far from nothing.”

He also suggested looking exactly where you want your wheels to go. In hairpins that means turning your head around over your shoulder to trace your exit line. “If you are looking where the bike is pointing, you will run wide. Look where you want to go.”

Boy, it works. I started doing all of my turning going in, and exiting on the far inside. This let me predict exactly when I could stand the bike up and blast out with full traction, setting up for a wide entrance to the next corner. It felt faster, safer and much more precise.

I was riding pretty well at the beginning of the trip. I got better every day.

Thanks, Christian.

The Real Disneyland

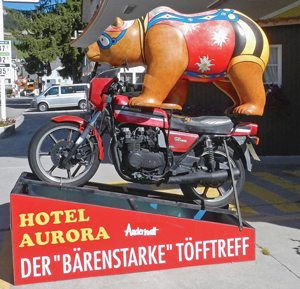

In the morning, we ferried across Lake Luzerne then snaked back to Andermatt. In 2002, my wife Kathy, my daughter TJ and I toured this route in our BMW 325i. I spotted a decomposing 1981 Kawasaki GPz550—just like mine—displayed in front of a bar. Eleven years later, it’s still there. Its seat is torn and the pipes are rusting. But its mirrors are still better than mine.

We stayed in Zermatt, the Disney-land of Switzerland. It’s an electric-vehicle-only village—we had to leave our bikes down the hill in Tesch and take a taxi-van up to our hotel. It was nearly dark. In daylight you can see the Matterhorn rising above the town like a huge Cat In The Hat. At night, not so much.

The Simplon Pass led us down to the lakes of southern Switzerland and northern Italy. We crossed Lago Maggiore—Ernest Hemingway’s escape route from Italy to Switzerland in A Farewell To Arms—to Laveno, and then Angela led us up over a paved goat track toward Lake Lugano, with its startling blue-green water.

Angels and Demons

The next day’s route led down to Lake Como, made famous by George Clooney, Maxfield Parrish and Moto Guzzi. We sailed across to Varenna, its ancient castle rising above the village. Fun medieval fact: Inside the castle tower hangs a bizarre collection of shiny steel chastity belts, designed for unhappy boys and girls alike.

I followed Angela, blazing on her Triumph Tiger 1200, up into the green hills and through one of the most exciting rides of my life. If I had been on my own, I would never have known these routes (SP62, SP25, SP26 and SP27) existed. It’s a paved motocross course, draped over contours that look like crumpled aluminum foil.

At the hotel, a tour mate reported that Angela had been riding “like a demon.”

“There’s a fine line,” I said, “Between angel and demon.”

Alped Out

We had three nights in Bolzano, Italy. I was content to sleep in, tour the town on a rented bicycle, have a pizza caprese and then collapse on my bed, sipping grappa and tonic. Christian led the next day’s circuit of the Dolomites, exploring every secret back road, mountain pass and soaring limestone peak. As usual, it was overwhelming. A trip like this challenges the ability of the human mind—mine, at least—to absorb so much beauty, and motion, and exhilaration. After a few days, I find myself what I call Alped Out. I need to catch up on what just happened, and how great it was, to make room for the next thing.

The weather had been perfect every day: crisp enough to make me appreciate my Aerostich suit, with just a few drops of rain. But on the last day, homing back north to Mieming, I found where the rain had been hiding.

I rode ahead on my own. Which got me into a nice rain squall that the others, passing by a half hour later, managed to dodge. The route took me over the much-touted Timmelsjoch, which I have been over at least three times, but have never seen. The whole pass was stuck in the middle of a cold, wet cloud, with visibility down to seven feet. All I could do was follow a couple of idling Porsche 911s over the top, hoping that if they drove over the edge, I would have time to stop before I followed them down myself.

The clouds parted long enough to make the final approach to Mieming, with its impossible sweep of granite and snow, just as gorgeous as it had been only 10 days before.

Edelweiss Bike Travel offers more than 70 motorcycle tours worldwide. The 10-day Ultimate Alps Tour is offered in June, July, August and September in 2014 and 2015. For more info, visit edelweissbike.com.

(This article This Close to Nothing was published in the February 2014 issue of Rider magazine.)