(This story was published in the July 2012 issue of Rider magazine.)

Story and photos by Clement Salvadori

My duties at Americade, up in Lake George, New York, were finished by noon—I could have been in Buffalo by nightfall, had I chosen to hustle along the Interstates. But that’s not much fun; might was well take a plane or a train. Two wheels are happiest on two lanes, and I was in no hurry. I wanted small towns, green fields, red barns, white farmhouses, cows and horses. Maybe an occasional chromed diner out of the 1950s with a feisty waitress and a thick cheeseburger on a properly toasted bun.

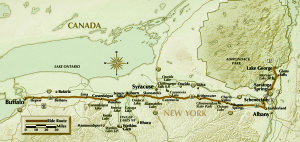

Get on US 20 in Albany and it’s a 300-mile doddle west to Buffalo. When this road was just a wagon-track connecting farming communities it was called the Great Western Highway, but designated US 20 in 1924 after the feds realized that motorcycles and cars were taking over the transportation in this country, and numbering the roads would make signage much easier.

After loading the Tour Glide that Harley had loaned me, I headed south toward Albany, about 50 miles. Looking at my map I saw that there was a short-cut to get from Lake George to US 20—turn at Saratoga Springs and take State Route 50 down to Schenectady, then a few miles of superslab and you’re on the US route.

Eventually I found myself joining US 20 in a town called Guilderland. This prompted a little 12th grade recall about U.S. history, remembering that the Dutch were here a long time before the English, and guilders were Dutch currency. With shopping malls and rows of suburban houses, there is not much in Guilderland to remind one of the fact that it was settled in 1629; now it’s part of Greater Albany. Finally I headed westward…on the Great Western Highway.

Back before our Revolutionary War, the British were not too happy about having the colonials spread too far afield…because it was too hard to collect taxes, some have written. Out west of Albany was all this good unused land, and a hardy few did go forth to clear the trees and plough the fields. But making any sort of cash living was difficult, as these farmers still needed to get their produce to market, and no wagon roads were being built.

After we declared independence from Great Britain, a lot of those brand new Americans wanted a plot of land to call their own, a house, and a family, and heading west was the answer. More farms meant more crops, cities like Albany and New York needed food, which meant building roads.

Like the Cherry Valley Turnpike, which was begun in 1799. Upon it I crossed the Schoharie River and went on to a valley where fruit trees flourished. Cherry Valley had actually been settled 60 years before, but the 50 miles to get the cherries to market in Albany had been mainly a one-horse trail. With this turnpike, which meant enough trees had been cut to allow wagons to get through, economics improved. Of course it was a toll road, because that’s how private enterprise worked: Build the road, and the folks who traveled on it paid a nominal fee. It stayed a toll road until 1857, but now that 200-year-old road is part of US 20.

The Harley and I cruised along a nice two-laner, when all of a sudden it turned into a four-laner with a very wide grass median strip. It had an old-fashioned look about it, rolling over the hills, dead straight. I slipped the Glide into 6th gear. This was the brief post-World War II expansion. War ended, gas rationing ended, new cars were available, America wanted to go traveling. And New York decided that U.S. 20, the main east-west route, would be enlarged. Then somebody pointed out that this old Great Western Highway was built in rural times, and did not go near any of the big cities like Utica and Syracuse and Rochester. “Let’s build a new one,” said the politicians, “the state and federal government will provide the money, and the road will pay for itself with tolls.” Just like olden days.

The New York Thruway was opened as a toll road in 1954, and traffic on U.S. 20 dropped by over 80 percent. In 1957, the Thruway was numbered as Interstate 90—and kept the tolls, unusual for most Interstates. Getting from A to B will cost about 15 bucks. If time is of the essence, money well spent; if you are on a motorcycle, take U.S. 20.

I took a little jog off the road to get to Sharon Springs, where hot water flowed out of the ground permeated with sulfur and magnesium. The local Indians had known about the healing and soothing properties of this place for generations, and in the late 18th century the new Americans knew all about the place. Following the recession of the early 1840s—yes, Virginia, there have been recessions in the past—New Yorkers were in a mind to spend some money. Big hotels were built, and visitors could come by steamboat and stagecoach, later by train, and the place flourished. Especially after the Civil War.

But by the turn of the 20th century, fortunes were waning, and Sharon Springs was becoming a backwater, the hotels and baths unmaintained and falling apart. Recently there has been a revival, and the old American Hotel, originally built in 1847 and now thoroughly refurbished, is a sparkling example of what can be done. It was a little early in the afternoon for me to be thinking about a bed for the night, and a place as nice as that deserves the attention of my wife.

Pushing on, I enjoyed wonderful miles of uncluttered roads. Even a little covered bridge that went off toward farms in the south. The locals have figured out a nice way to make a little extra money. For a hundred miles it seems that every village and town has a couple of antique stores, a lot of them looking like ordinary houses, most of which were closed on this mid-week day, usually leaving some of the less valuable “antiques” on the front porch. At a gas station I asked what the deal was. The attendant laughed and said that this is a tourist zone on the weekends, and anybody with an attic full of junk hauls it out and waits for the city slickers to come by and pay outrageous prices for an old cane chair that needs a new seat. Or grandpa’s fiddle that cracked 50 years ago.

Riding through Cazenovia, I knew that I was in the beginning of the Finger Lakes region. These 11 lakes all run north-south as a result of glacial erosion some two million years ago. The land is remarkably fertile, especially with grapes, as the area turns out the best wines in New York State.

Moving on for 30 miles, the road goes by Skaneateles Lake before coming into Seneca Falls, where I made a brief stop at the Women’s Rights National Historical Park. Back in the 1840s, this was a highly industrialized town, with the rushing water of the Seneca River powering the mills, and home to a woman who was tired of men always running the show. Elizabeth Cady Stanton organized the first women’s rights convention in that town back in 1848, when this group declared that all men and all women, colored as well as white, were equal. It took another 71 years for the ladies to get the menfolk to pass a constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote, but it all began here. Seneca Falls has an important place in our history.

The Thruway was only a couple of miles north of here, the closest that the new road and the old road get together, but I had no interest in that. Instead the Harley took me on to Geneva, only 10 miles away at the north end of Seneca Lake, which has a beautiful state park right on the water, with a 200-slip marina. The lake is about 40 miles long, and would be great sailing on a breezy day.

I took a look at my map. I’d come farther than I thought on this long, late-spring day, only 100 miles to Buffalo. It was time to find a motel.

Morning brought clear blue skies and the television weatherperson told me that the temps would be in the seventies. Perfect riding weather. The Harley cranked up with the push of a button, and I trusted that the stock exhaust wouldn’t wake anybody still sleeping. Traffic on the two-lane road was very light, only an occasional local. I was beyond the Finger Lakes tourist zone, and the day promised countryside, small to middling towns, farms, crops and pastures. I didn’t need drama all the time; a pleasant ride with good sights and fresh smells did me fine.

The road connects towns that were formerly a day’s ride apart on horseback, built when horses were the common transportation. I got to Lima, a small town celebrating itself as the Crossroads of Western New York, and found another American Hotel at the crossroads smack in the middle of town. This is a three-story brick edifice dating from about the same time as the Sharon Springs hotel, in the 1840s, and also on the list of historic places. I could imagine the local movers and shakers hanging out at the bar, 150 years ago or today.

The road was straight, crops were growing—take the asphalt away and this could have been a hundred years ago. Except a century ago the town of Bethany was prospering, with the waters of the Little Tonawanda Creek powering gristmills, sawmills and woolen mills. All gone now. Probably most citizens commute to work in the city. That’s life, that is change.

The Harley and I came into the outskirts of Buffalo. As we reached Depew, U.S. 20 took a right turn to the south. In the 1890s, the New York Central Railroad decided Depew would be a useful place for major railroad operations, and factories were set up to refurbish the rolling stock that always wore things out. Industry is pretty slack nowadays.

But I didn’t turn to stay with U.S. 20. I had one stop to make in Buffalo, straight ahead. An enterprising couple set up the English Pork Pie Company and does mail order business all over the country. I wanted to stop in and get a couple of pies and sausage rolls hot out of the oven. Delicious! I was set for the rest of the day.