Whoever said a straight line was the best way to get from Point A to Point B didn’t ride a motorcycle. Is there anyone among us who uses a freeway rather than backroads as their main source for motorcycling entertainment? Not many, I dare guess.

When President Eisenhower came up with the notion that the United States needed an Interstate Highway System, was there anyone on his staff who insisted that a few bends in the road might be a good idea? If that conversation ever took place, can there be any doubt that the person rode a motorcycle? The unnamed guy who liked the Point A to Point B straight line seems to have gotten the final word.

Check out some of Rider‘s Favorite Rides

Back during the advent of the motorcycle and the automobile, the earth set the agenda for where roads were constructed. Pick any of the older highways, and there’s every probability that it wound around a hill or paralleled a river. Over time, with more potent explosives and bigger and better earth-moving equipment, the scales were altered, and it became easier to make the good earth bend to every highway engineer’s wishes.

Over millennia, glaciers and the earth’s upheaval created the glorious hills and majestic mountains we all enjoy. Over a few decades, the big Ukes (that’s what we called the Euclid earthmovers when I was a kid) scraped up tons of hillside to fill in deep valleys, creating what the highway people knew we needed – a quicker way to get from here to there. Okay, I admit, some of it worked.

When you step down a rung or two from the freeways and turnpikes to the more basic highways, you quickly find where they have been remade for a more effortless trip to get us to grandma’s house or church in the next city. Filter down even further to where the true old highways are, to where there’s a rawer feel, more of the essence of when the old roads were created, many have an ebb and flow where what’s around the next turn is still a mystery to be enjoyed. That’s where I aim my motorcycle, where there is still an unknown, where those bends in the highway invite me back again and again.

Certainly, there are exceptions. Straight-as-an-arrow U.S. Route 2 across the northern U.S. is an exceptional ride, so much so that I once saw it on a Top 10 Highways list. Even so, it was better 40 years ago when it was only two lanes. There are stretches of I-70 in Colorado and Utah where it’s a wonderful ride, a rarity when one considers how interstate highways are traditionally perceived.

Given a choice, we all know where to aim our motorcycles – somewhere in the spirit that William Least Heat-Moon wrote of in Blue Highways and Jack Kerouac in his epic On the Road, where the roadway has a soul, a vibrancy, a purpose beyond being a simple means to get to somewhere distant.

The original National Road, U.S. Route 40, called the Main Street of America, still has a romantic ring to it, at least to me. That highway actually is Main Street in my hometown of Zanesville, Ohio, home of the famous (at least to those of us who know it well) Y-Bridge, a part of that highway’s mystique.

Riding Ohio’s Triple Nickel: State Route 555

But that title – Main Street of America – is also claimed by U.S. Route 66, the almost mythical highway known by other famous names, such as the Will Rogers Highway and the Mother Road. To those of a generation long ago, Route 66 represented a way to leave behind pain and despair, the highway itself a lifeline to a place where life would have purpose. At its inception in1926, it was called the Great Diagonal Way, but that same year the U.S. set forth the numbering system for federal highways that’s still used today.

From that original numerical foundation there have been other designations for our well-known and lesser-known highways. U.S. Route 6, which stretches from Massachusetts to California, is called the Grand Army of the Republic Highway; part of U.S. 20 through Nebraska is known as the Bridges to Buttes Scenic Byway; U.S. 12 across Montana is the Lewis and Clark Highway. The Buffalo Bill Cody Scenic Byway is in Wyoming, the Schoodic National Scenic Byway is a part of U.S. 1 in Maine, and the Catskill Mountains Scenic Byway is in New York State.

U.S. Route 23 in Kentucky is called the Country Music Highway, claiming to be the home of many country music icons, including Loretta Lynn, The Judds, Billy Ray Cyrus, Dwight Yoakam, and Tom T. Hall. A six-mile stretch of U.S. 129 near Robbinsville, North Carolina, is known for its favorite son – the Ronnie Milsap Highway.

The list goes on and on. At the time of this writing, there are 184 nationally designated scenic byways. If you travel almost anywhere, you’ll find our nation’s history in the names assigned to our highways.

Then there are other highways offering a different experience: the highway itself. When the letters PCH come up, is there any doubt what they refer to? For those of us who travel on motorcycles, there are blacktopped magnets we are attracted to. We’re drawn to special places by what the pavement has come to represent. The Tail of the Dragon and the Cherohala Skyway, both winding through the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee. The Million Dollar Highway in the Colorado Rockies. The Great River Road along the Mississippi River. The old Lincoln Highway, where some stretches can still be found. And for many, the Natchez Trace and Blue Ridge Parkway. Or maybe not. Sorry, beautiful or not, a 45-mph speed limit is not for me.

Other state highways take on a more specific meaning. Twenty memorials mark the 54-mile Selma to Montgomery March Byway, the route taken by Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights activists, chronicling their march and its results. For those who pursue history of another era, the 180-mile Journey Through Hallowed Ground Byway, spanning Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, is said to contain more historic sites than any other in America. Then there is the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway, which connects Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks. It’s named for the late conservationist and philanthropist who was so disturbed by the condition of the highway, he paid to have it brought up to the standards of the day.

For those with a need to know or who are curious, as of 2019 there were 4.2 million miles of roadway in America, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation. There were approximately 48,482 miles of interstate highways; although such highways account for just 1.2% of roadway miles, they account for nearly a quarter of all vehicular traffic. Of the 4.2 million miles of roadway in this country, 2.9 million miles are rural roadways and 1.2 million miles are unpaved. No matter how you crunch the numbers, there are lots of roads to explore.

Every state does its best to help, identifying scenic routes with signs and official designations, with every road map marking them in a special way so they’re easy to recognize. They are generally where I aim my motorcycle. Let me trust the state to point me to a highway it considers special, the smaller its fame, the better.

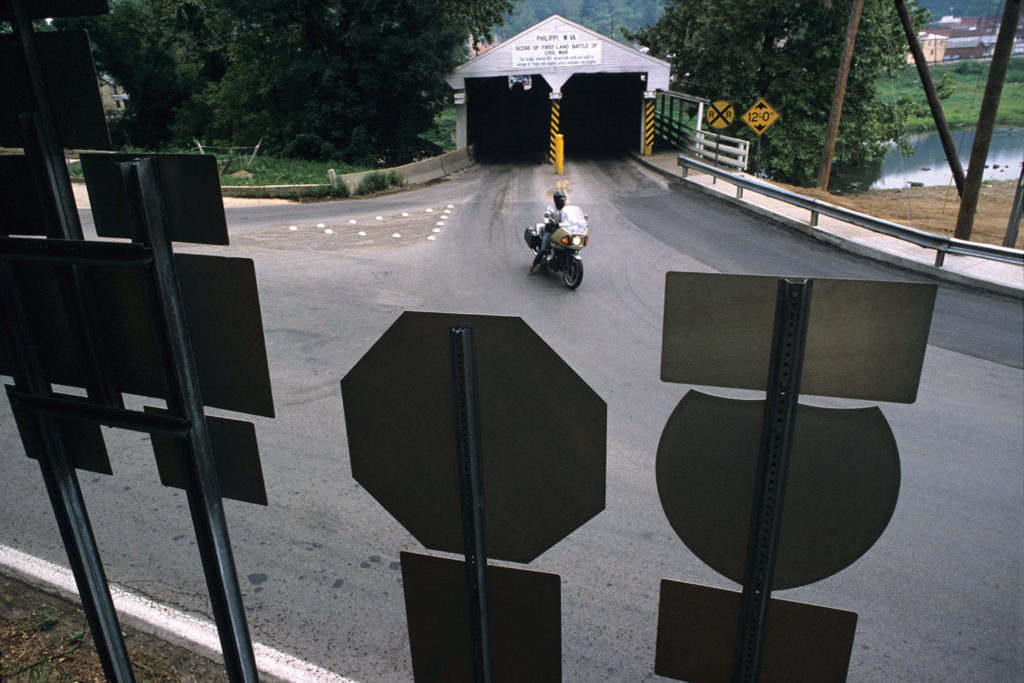

The photographs on these pages represent some of the special places I’ve found. They are a part of my nearly six-decade personal history of riding motorcycles, chronicling the changes in my life, both in terms of the motorcycles I’ve ridden and in how I perceive the wonderful places along my many miles of riding.

Most appeared out of nowhere, a stunning place before me, something that I needed to record for myself, and now share with you. In all but a few places they were surprises, riding around a turn in the highway or over a hilltop and there it was, a special stretch I’d never seen before. Sometimes, in that instant, it was only me; other times unknown people on their motorcycles happened by. I hope some who are in this collection, should they ever see these images, find themselves being transported back to the time our paths crossed.

Some are from so long ago I have only a general idea of where they were found. But, thinking back, their location isn’t what was important. It’s what that stretch of highway represented to me at the time and where it still lingers in my mind. What I knew, then as I do now, is that there is another great memory, another beautiful stretch of highway soon to be enjoyed. Now to go out and find it.

Really enjoyed your article. Also being from SE Ohio (Marietta) I have enjoyed many of the roads you mentioned, in Ohio and West Virginia. I’ve also experienced those special sections of road that harken back to a time when speed and time were’nt the primary reason to travel that route.

Route 2 is still an amazing road. Two years ago I drove it heading home from Glacier NP to Minnesota where I cut south. Right outside the park I passed under a freight train on a bridge and despite periodic rest stops the train and I leap frogged each other for the next 300 miles. Narrow road, endless vistas, no traffic, the way marked by small towns every so far each with their own distinctive water tower. To describe it would be a hard case to convince someone it is worth driving but with the right eyes such a road can take you back in time.