by Perri Capell; photography by the author and Lynn Brown

It was twilight when we pulled into Cao Bang, and traffic was picking up. Digby, our guide, motioned to us to park the Minsks at a nondescript building on a street corner about halfway into town. There a grinning man approached carrying a small compressor, a spray wand and a hose.

It was northern Vietnam’s version of a car wash and a welcome sight indeed. It had rained all day, and the dirt roads we were riding in the highlands of northern Vietnam along the Chinese border had turned into streams—nay, rivers—of mud. Not only were the bikes coated with a thick goo, but all our gear and clothing were as well.

The seven of us riders needed washing as much as the bikes. In between spraying the motorcycles, the proprietor amiably sprayed us down as well. Muddy water poured off our rain ponchos, pants and boots. In all our combined years of riding, we had never been as muddy as we were on this trip.

The personal wash job ensured us a stay that night at the hotel in Cao Bang. This city of 45,500 is a provincial capital and the largest we visited during our eight-day ride. But its relatively luxurious Bang Giang Hotel, run by the local government as are all the hotels we stopped at in northern Vietnam, didn’t like muddy Western motorcyclists tramping through its lobby. We were also told to not use the white bath towels to clean our boots because the hotel laundry couldn’t get the mud out.

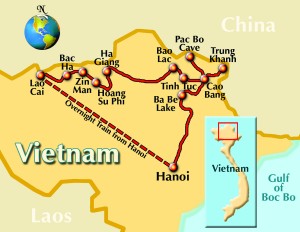

Far dryer and cleaner, we had started out three days earlier in Hanoi. There we met Digby and Thuan, our Australian and Vietnamese guides respectively, with Explore Indochina, a Hanoi company offering adventure motorcycling tours in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. Our plane to Hanoi had been delayed, so we had arrived later than expected. The plan was to take an overnight train to Lao Cai, near the Chinese border. The guides whisked us to the train station just in time to load the bikes and take occupancy of two four-berth compartments.

The best strategy for overnighting on a Vietnamese train is to drink a few beers and take a sleeping pill. Not knowing this, I thrashed around in an upper bunk and held off as long as possible before using the moving-target, hole-in-the-floor toilet at the end of the train. I was the only woman on the trip, and I got to know the squat toilets in Vietnam pretty well.

Believe it or not, this was our honeymoon. Lynn and I had married the previous summer but hadn’t gone anywhere relaxing or exotic after the wedding. Somehow he persuaded me that riding Russian Minsks in what the French had called the Tonkinese Alps of northern Vietnam would be the perfect belated honeymoon trip. Having done a bit of dirt riding in other countries, I warmed to the idea. It was only after I returned to the United States, sore and black and blue, that I read the company’s brochure about the trip. “This route is very remote, like a ‘black’ ski run, and conditions can be basic,” it said. “Degree of difficulty: Difficult.”

So it was not your typical honeymoon. Little did I expect to be reverting to childhood and filling my days, face shield and boots with mud. If January, when we were there, is the dry season, I would hate to see what the roads are like during the rainy season.

Every day we experienced new challenges: new textures of mud, deep stream crossings and steep embankments. I wasn’t a mud rider before I left, but I sure was when I returned. But while northern Vietnam in January was cool, damp, muddy and primitive, it was also breathtaking and extraordinary.

The Chinese have long made scroll paintings of conical limestone mountains covered with moss and decorated with waterfalls and streams. These mountains are called karst. The part of northern Vietnam we were in looks like that. We traveled 100-150 miles daily along high mountain roads that skirted terraced farms and took us through rural villages.

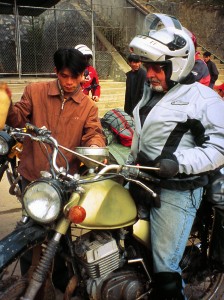

Our steeds for the trip were rented Russian Minsk motorcycles, 125cc workhorses that kept on going and going. Northern Vietnam doesn’t allow bikes with larger engines, and the Minsks are ideal for the terrain we encountered. They are seemingly indestructible and able to get through the toughest conditions. No two are alike. One might be missing first gear, another might lack seat padding and a third might not have a working clutch.

Still, I was as impressed with the kickstart Minsks as I was with the country. They always got the job done, plowing up hills of mud or through deep streams in low gear. Fuel was a mixture of gas and oil poured directly into the tank. When (not if) we dropped the bikes, Digby and Thuan carried spare parts to quickly fix a broken clutch lever.

For more complicated jobs, local mechanics were terrific—and cheap! When the transmission on Lynn’s Minsk had to be rebuilt, the mechanic in Cao Bang who fixed it only charged $12.

After the train ride to Lao Cai, we unloaded the bikes and started riding, excited to be underway—if a bit bleary eyed. Our first stop was by the Red River separating Vietnam and China. It seemed astounding to me to be on China’s border and see the traffic bustling back and forth over a wide bridge separating the two countries.

As we rode out of town toward the remote highlands, it quickly became apparent that most of northern Vietnam’s roads in this region are under construction. When building roads, Vietnamese heavy-equipment operators don’t create detours for vehicles around the construction. You ride through the construction in a general free-for-all with backhoes, cars, buses, motorcycles, scooters and bicycles in either direction choosing the best option. If a bridge is being constructed over a stream, you’re routed through the stream. Besides becoming a mud rider in northern Vietnam, I became a stream rider as well.

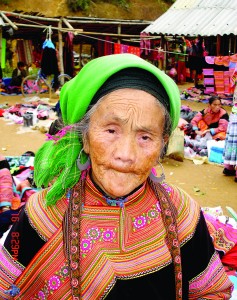

We traveled north and east toward Xin Man, soon spotting members of some of Vietnam’s many hill tribes, such as the Flower, Green, Red, Black and White Hmong people. They are among the 50 minority groups in Vietnam who stay mostly to themselves, avoiding national conflicts or politics. They live much as they always did on the hillsides, farming their terraces, tending water buffalo and other livestock, making colorful clothing and selling their wares at local markets. Each tribe has a distinctive style of dress usually made with vibrant pinks, greens, yellows and other colors. It was wonderful to encounter them while they are still mostly unaffected by Western culture.

Xin Man and the other small towns we stayed in—Ha Giang and Bao Lac, as well as Cao Bang—typically have one relatively new “Western-style” hotel run by the local Communist party. This means they have bathrooms and plumbing. Quality varies widely. We were grateful when the beds had covers, the bathrooms had hot water and the sinks were plumbed. I looked forward to the insulated canisters of boiling water and tea placed outside the room when we arrived, and refreshed in the mornings.

Little English is spoken in the northern highlands, and at mealtimes we would not have known what to eat—or what we were eating—if Digby and Thuan hadn’t ordered for us (and insisted that we never ate dog, cat or snake during the journey). Often our meals were cooked over fires in humble storefronts. Typical dishes included omelets, tofu with tomato, spring rolls, stir-fried vegetables and stir-fried meats. Vietnamese custom is to serve rice and soup at the end of a meal “to fill in the spaces,” Thuan told us.

Breakfast is usually the same noodle soup called pho (pronounced “fir”). But thank goodness for the country’s French heritage and remaining French cuisine. The warm French baguettes and strong coffee in the morning were delicious. For lunch, the guides laid out picnics of meats and cheeses with fresh local lettuce and tomatoes and baguettes. We didn’t go hungry!

Western motorcyclists are quite a sight in the sparsely populated region. We’re much larger than the Vietnamese and our motorcycle clothes and helmets probably made us seem like aliens. Western women are considered “soft” and so the villagers were particularly surprised to see me.

Highlights of the trip included stopping at the local markets, where we could joke and bargain with the hill tribe people, and meeting children in villages along the way. Although giving gifts isn’t encouraged, we brought chalkboards and chalk for the children. Vietnamese children are told that they will be sold to Westerners if they are bad, so they ran away from us when we stopped near their houses. They were less scared of me than the men, and eventually curiosity would get the best of them. Soon I’d have an audience of 20-30 children and villagers watching as I drew pictures to show them how to use the chalkboards.

In one village, I admired a young girl’s tribal earrings made of hammered metal. With smiles and gestures, her mother asked if I wanted to buy them. I said yes, and we agreed on a price of 18,000 dong, the country’s currency. The earrings were mine for just over $1.

The switchbacks up the mountain passes and into the canyons were typically second-gear and sometimes third-gear riding that took us by terraced farms. We rode on dirt, gravel, rock and paved roads, paying attention to oncoming trucks, which took up most of the road. Sheer drop-offs at the berms kept us on our toes, and we frequently reached altitudes of more than 3,000 feet. Water buffalo roamed freely, as did pigs, dogs and chickens (we didn’t see any wild animals and birds, which have been hunted to near extinction except in the national parks). Per Digby’s instructions, we would lay on our horns Vietnamese style, particularly when we wanted to pass another vehicle. If it didn’t move to the right, we kept honking until it did.

Wet and dirty when we arrived in Cao Bang, we stayed two nights to dry out. At Digby’s suggestion, we visited a hair-wash parlor and had our hair washed by a lady with long fingernails. Trust me, it’s an unbelievably sensual experience.

Cao Bang is near where Ho Chi Minh hid from the French. Not far from our hotel, we stopped to see Ho’s statue, probably the largest in the world of anyone holding a cigarette. On a rest day we rode to nearby Pac Bo, where in 1941 Ho re-entered Vietnam from China, where he had been hiding, and lived in a cave while writing key revolutionary tracts. The cave site contains Ho’s bed and desk and is a national shrine.

From Cao Bang, we journeyed to Ba Be Lake in Ba Be National Park, a tropical rain forest area surrounded by high mountains. The boatmen loaded our bikes on two boats and we piled into a third. We then motored along the serene lakes and through a cave to a scenic lodge, where a power outage that night meant eating and retiring to our rooms by candlelight. If we weren’t so tired and dirty, it might have been romantic.

By now, we were nearing Hanoi and the end of our trip. The next day began in the scenic park and ended in mad-dash combat riding into bustling Hanoi, where traffic is insane and shopping is fabulous. You would think we had enough of riding motorcycles in Vietnam, but we’re going back soon on another adventure with Digby and Thuan.

For more information on Explore Indochina, visit www.exploreindochina.com.

[From the October 2006 issue of Rider]

I’ve been exploring for a little for any high-quality articles or weblog posts on this kind of house . Exploring in Yahoo I finally stumbled upon this website. Studying this info So i am glad to convey that I have a very just right uncanny feeling I found out exactly what I needed. I so much indubitably will make certain to do not put out of your mind this web site and provides it a look on a constant basis.

I miss vietnam so much.