story and photography by Clement Salvadori

A new motorcycle sits in the garage, and I want to take a short motorcycle ride through Kern County before the owner calls for its return. The owner is Victory Motorcycles, the bike is a Kingpin Deluxe that has been loaned to Rider for an evaluation. The road test has been done (2006 Victory Kingpin Deluxe Motorcycle Review), but I want to see what the real-life aspects of the Kingpin are, what it’s like to live with for a couple of weeks, get the groceries and such. The Deluxe indicates that windscreen and saddlebags come standard on the Kingpin, making it my preferred kind of ride.

This little bit of heavy thinking is going on while I am frying up eggs and bacon, buttering up my toasted sourdough bread, and pouring my second cup of dark-roasted coffee. A man’s gotta eat. And a Victory has to drink…gasoline, that is. Maybe I should head out to where some of the Victory’s food/fuel comes from.

Eighty miles due east of me are the Elk Hills and an oil field of the same name, which was at the heart of one of the more notorious scandals that ever rocked the government of this country, the Teapot Dome affair. That was 80 years ago, but politicians still wince when the subject comes up. It was the way political business was done back then, just a little matter of making a profitable deal, with a goodly amount of cash being discreetly transferred from the account of a well-connected businessman to a member of the President’s cabinet. More on that in a bit.

Today is a cool late-winter morning, with the forecaster promising a high of no more than 60 degrees. All you

Minnesotans will laugh at this, since the temperature in Minneapolis won’t reach 30 degrees on this day, but that is why I have chosen to live in California, so I can go riding in the middle of January. At 60 degrees, though, warm clothes are in order. I roll the ’Pin out, clean a few bugs off the windscreen, put a tubeless-tire fix-it kit in one saddlebag, my camera in the other, and we’re away.

The Kingpin is low-slung, with a seat height of 27 inches, but I fit it well, boots firmly planted on the footboards, wide tiller bar making it easy to keep this 700-pounder on line. We stop at the Victory’s favorite fast-food spot, where I top off the 4.5-gallon gas tank with expensive high-test. I can almost hear a burp of pleasure.

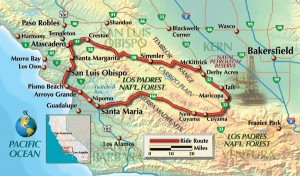

Our direction out of town is pretty much due east, navigating along twisty roads, and soon we are rolling through ranching country, everything from Herefords to Texas Longhorns providing America and the world with beef. Medium-rare, please. There’s even a small herd of buffalo down at the Camatta Ranch. Route 58 is a two-lane road with minimal traffic and lots of curves, and I only knick the transmission into sixth gear on the long straights, that top gear being very much an overdrive. We cross over the Carrizo Plain with the Temblor Range of hills straight ahead.

That’s geology for you. A big earthquake fault, the San Andreas, runs right through the Carrizo Plain, and out here on the plains there is naught but grazing land. Hard to get rich on that. Cross over the Temblors and drop into McKittrick Valley, and we’re on top of one of the richest oil fields in North America. I should add that the drop down from the Temblor ridge into the valley is as fine a piece of riding as one can hope for, and the ’Pin enjoys a good deal of cornering clearance considering its cruiser status. The fork springing is a bit on the soft side, intended more for comfort than handling. I would have liked to fiddle with the preload on the single shock a little, but it really is difficult to get to, so I didn’t. A minor drawback, though it is the only adjustment in the suspension system.

That engine, however, is a work of art. I’ve put many miles on Victory’s Touring Cruiser with the original 92ci/1,507cc engine, but haven’t many hours on this newer 100ci/1,634cc version. And it is fun. Whack that throttle in third, and we’re at 90-plus mph in a long heartbeat. The OHC 50-degree V-twin is a happy revver, and will garner respect wherever it goes; the counterbalanced engine is quite smooth, and vibration was never a problem. With intelligent abuse of the gearbox, this baby will fly.

The Elk Hills are in the western part of a large California county called Kern, named after one Edward Kern, a mapmaker who came into California in 1845. But that is all ancient history, and the Kingpin and I are rolling through the western section of the county in 2006. To give an idea of size, this one county covers some 8,000 square miles, bigger than my home state of Massachusetts. It is also reputed to be the richest county in California, though the money is not readily visible, as the wealth comes from oil and agriculture. The old boy with bib dungarees and a straw hat in the beat-up pickup just may own 10,000 acres of well-irrigated farmland, the land that feeds a lot of America. Or have a long-term lease from an oil company, and a few thousand shares of Exxon/Mobil stock in the safe-deposit box.

While we mortals nosh on a steak and salad, my Kingpin sips the oil that lies beneath the surface. And that is the real story here. We used to take oil, and its distillate, gasoline, pretty much for granted, until the price of crude went over $60 a barrel. Now all that petroleum figures large in the way the world does business; in truth, it drives the world’s economy.

The ’Pin and I head down Reward Road and stop to take a look at a drilling rig poking yet another hole in the ground. Within a mile a thousand pump-jacks, those nodding contraptions many of us have seen as we’ve traveled this great land, are already pumping away, but one more means more petroleum will be pumped up to the surface. The Kingpin watches the drilling crew and approves.

A roughneck comes over to ask what I’m doing. Writing a story on this new bike, I say, taking pictures of life’s necessities. Don’t get too close to the rig, he says, things do fall, and when that happens it’s best to just get out of the way. I show him my shortened finger, a product of my not getting out of the way while working on a rig in East Texas some 40 years ago. Yeah, you understand, he says. That’s a real pretty bike, he opines, and he speaks the truth.

People have used petroleum for thousands of years, as a crude tar to waterproof boats, or for medicinal purposes. European cities like Prague were using it for lighting streets as long ago as 1815. Back in the late 19th century the main combustible product distilled from petroleum was kerosene, which lit many lamps. Small change, really, and it was the development of the oil-fired boilers on ships, and then the internal combustion engine, that really prompted the search for oil.

A hundred years ago the U.S. Navy realized that heating the boilers on a steam-powered battleship with oil was a lot more practical than shoveling coal. President Teddy Roosevelt felt that America should secure its own supply, and directed that the 30,000-acre Teapot Dome oil field in Wyoming and the 70,000-acre Elk Hills field become the first U.S. Navy Petroleum Reserve, established in 1910. All well and good, until Warren Harding became President in 1921, a gent often referred to as the worst president this country has ever had. His Secretary of the Interior, a fellow named Fall, convinced Harding that the reserve should be leased to private companies, which could make exceptional profits out of the deal. Fall was later convicted of taking large bribes from the companies that secured the leases, and the reserve was returned to the Navy’s control. Until it was sold off to Occidental Oil in the late 1990s.

It was said by the charitable that Harding died of a broken heart, brought on by the many scandals in his administration, but I prefer to think that his wife poisoned him for his many infidelities.

The Victory Kingpin and I stop off at the McKittrick Hotel for a working-man’s meal. The town of McKittrick claims some 2,000 inhabitants today, and they all live off the oil industry, whether it is working as roughnecks and roustabouts in the oil fields, or serving them up chicken-fried steak for lunch. The owner of the hotel, Mike Moore, has amused himself over the years by gluing over a million pennies to every flat service he could find in what is now known as the Penny Bar. The hotel is a recommended stop for any motorcyclist in that part of the world. Don’t worry about an address, as there are only three buildings left on McKittrick’s main street. Sorry, no rooms available, but lots of high-test food.

The ’Pin and I head south on Route 33, and the next few miles to Derby Acres run through a pretty vacant landscape. The oil around here has developed in big pools, and we’re leaving one pool and heading to another—where the view is quite astounding. Pump-jacks and pipes are absolutely everywhere, as far as the eye can see. Off in the distance I see a steam plant smoking away. Getting oil out of the ground is a complicated art, and after the easy part is over, with all the liquid crude that is easily found pumped up and piped or trucked off to refineries, then the hard part starts. Pump water into the wells, and the remaining fluid oil floats. But the company also wants to get the sticky stuff that is still down there, so the water is pumped out and then steam injected, heating up the underground and liquefying the petroleum tar.

I look at all this equipment, covering thousands of acres, and it seems that the $2.50 I’m paying per gallon is pretty reasonable. (Of course, as this goes to press in May, the price has been upped to $3.50.) Oil geologists estimate that there are more than a trillion barrels of oil under the ground in North America, another 5 or 6 trillion in the rest of the world. We’ll probably use most of it up in the next 40 or 50 years, but we can hope that some bright light will have come up with another source of energy, like hydrogen or rainbow vapors, so that we can keep motoring along.

We get to Taft, where the 7,000 people depend on the oil fields for a living. Nice little town, if you don’t mind the smell of oil in the air. The local college offers all sorts of classes in matters concerning oil. On the south side of town is the West Kern Oil Museum, where a hundred years of oil-field equipment has been preserved. Including a wooden derrick that was built in 1917; it was dismantled about 30 years ago, and set up at the museum in 2005.

For those who have never thought about it, the principle behind those tall derricks is to have a place to store the long pieces of pipe that are used to drill the hole in the ground. Drilling is often a slow, boring job, but when the drill bit gets dull and needs to be changed, that is when the activity occurs. Haul up and stack 15, 30 or 50 pieces of pipe, change the bit, and then put all of it back in the ground. The ’Pin is glad it doesn’t have to do the work; it just enjoys the liquids of the labor. And does not even have to bribe anyone, as I am picking up the tab.

Time to head home. We go west on Route 166, a good cruising road with smooth asphalt (made of petroleum) and languid curves. Getting to the coast, we turn north on U.S. 101 back toward home. A 250-mile day is a piece of cake; the Kingpin Deluxe does provide a good touring ride. As well as daily transport, since I remember to pick up the lamb chops and broccoli for dinner.

[From the August 2006 issue of Rider]