photography by Jason Critchell

Anniversaries (from the Latin anno, or year) are celebrated in different ways. The first, second, 25th, 50th, whichever, harkens back to an event, whether it is a birthday, a wedding (Sue and I celebrated our 20th this year), a battle…or the creation of a new motorcycle model. An anniversary is not a re-creation of that day, but a recognition of the event, and to this end Triumph has built 650 (for the 650cc of the original) 50th anniversary models, of which fewer than 200 will come to this country.

I had the good fortune to be asked to go to the Triumph factory in Hinckley, England, to do this exclusive on the 50th. The downside is that it requires some 10 hours in a noisy, cramped airplane to get from Los Angeles to London, but British Airways fed me well…and seemed to have an unlimited number of those little bottles of red wine to keep me pleasantly sedated.

I got to Hinckley that evening, where my hotel had the Triumph pub, with a Sprint mounted over the bar, and lots of Triumph parts decorating the place. The next day I had a sit-down with Simon Warburton, the product manager, who told me that Triumph now has two factories in Hinckley, with three more in Thailand. In today’s global economy this is the efficient way of doing business, making the best product possible at the lowest price. The Bonneville engines are built in Hinckley and then shipped off to the Far East.

In the 2008 model year Triumph built more than 48,000 motorcycles, and the number grows every year. As a point of reference, the best year that the old Triumph company had was 1969, building 47,000 machines. Warburton said that the North American market takes the biggest share of Triumphs, over 27 percent, followed by the United Kingdom with 15 percent. That will soon be overtaken by the French and Swiss motorcyclists which now take 14 percent, and whose markets are growing. Triumph has 740 dealers all over the world, from Japan to South Africa to Argentina.

After giving me a computerized presentation for the 50th model, Warburton passed me along to Trevor Barton, officially listed as the product coordinator, the man who makes sure that all the minor details that make up the big picture are successfully worked out. He took me into the working part of the factory, which in this modern day and age is quite a sight. I was at the old Meriden Works twice, in 1960 and 1978, with oil-soaked wood floors and workers actually heating up the tubes and bending them manually into the frame. Here the concrete floors were swept clean, and sophisticated machines did the final touches on swingarms and cylinder heads. In the warehouse big boxes of all the hundreds of bits and pieces required to build a motorcycle were neatly stacked on shelves running to the roof more than 40 feet high, and forklift operators brought down what was needed to put on the two assembly lines.

Employee satisfaction is important to Triumph’s owner John Bloor, as that means low turn-over. The vetting process to get a job is involved, but the end result means that workers tend to stay around a long time. The company provides work shirts with each employee’s name on the pocket, which is good for morale. I watched Sprints and Tigers getting put together, and each work station had a little more than two minutes to get its job done. Anybody who has ever worked in a factory with an assembly line can appreciate the skill the workers need to have to get the job done on time.

At the end the bike was put on a pallet and surrounded by a thick cardboard box, with a small sticker having a description, a number and a bar code. I looked at a box on which the sticky was numbered 360136, and the contents listed as a Sprint ST ABS Tornado Red. Barton told me that was the sequential number to show how many Triumphs had been produced since 1991. Three hundred and sixty thousand! That’s a lot of Hinckley Trumpets.

Next morning I showed up in my riding gear and Jason Critchell, the shooter, was there. We discussed what would be needed for the magazine–horizontals, verticals, static, riding, all mixed up with some traditional English scenery. But mostly we needed to make this anniversary bike look good, which would not be very difficult. We went outside to have a look at my day’s ride, the first time either of us had seen it.

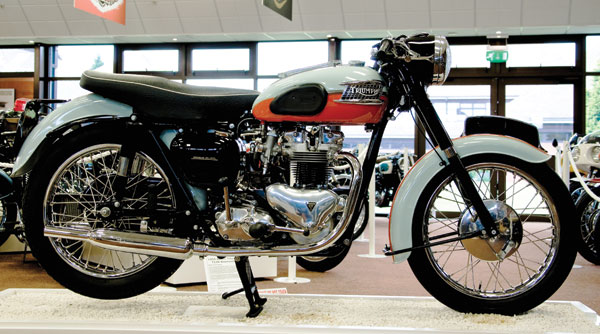

This anniversary edition is based on the T100 model, and is both attractive and subtle in its connection to the past. The paint is the key, and that had been one of Barton’s accomplishments. The original ’59 Bonnie used a bluish Pearl Gray and Tangerine, with gold lines separating the colors. Edward Turner knew that a bit of chrome to glitz things up was always appreciated, and the Triumph gas tanks at that time had a chromed strip covering the seam that ran down the middle of the tank, and the infamous chromed package grid mounted on the tank as well as chromed badges on the sides. The anniversary model has kept true to the colors, though with different names, Meriden Blue and Exotic Orange, and gold dividing lines. No chrome strip runs down the middle of the tank, and the package grid is long gone, but the chromed badges are still there. The cam covers on the engine are chromed to help provide that essential glitz.

Equally important for the anniversary version is the black handlebar clamp which has a small plaque reading LIMITED EDITION with the serialized number in the 650 written below. I would be riding Number 1, which, if I did not crash it, should eventually go to John Bloor.

Other anniversary tidbits are the white piping on the seat, and the Triumph logo at the end of the saddle being written in gold–for the golden anniversary. Both side panels have 50th anniversary decals. The instrument panel is finished in black, and the Triumph name is now molded into the rubber footrests. Fork gaiters are standard; these are not only very retro but also very practical, as they do protect the fork seals.

Being an overcast morning, which Critchell said would improve with time, we chose to go 30 miles west to the refurbished National Motorcycle Museum on the outskirts of the city of Birmingham and take some photos of a genuine ’59 Bonnie. He would take the big roads with his van, while Barton would lead me via the small roads–and they can get delightfully small and narrow in the English Midlands.

All ’09 Bonnies will have Keihin fuel injection, cleverly disguised to look like the carburetors we have seen for the past eight years. There is no choke, just the fast-idle pull-out, and it started up instantly and within a mile I had pushed the knob back in. I only put a hundred miles on Number 1, but in that brief period I could detect no glitches with the injection system, and it ran as smoothly as my carbureted ’06 T100 which has 10,000 miles on the odometer.

This T100 is an easy motorcycle to ride well. The ergos are right, the drivetrain has smooth power delivery, and the chassis handles the curves very well. Of course, if you want to get a knee down, you buy something like a 675 Street Triple and take it out on a track day, but for the pure pleasure of riding, it’s hard to beat a Bonnie. It is the real essence of motorcycling.

The short-stroke 865cc vertical twin engine, 90mm bore, 68mm stroke, is a happy little revver, generating about 60 horsepower at 7,000 rpm, 50 lb-ft of torque at 6,000 rpm. Five speeds in the transmission kept the fancily dressed T100 moving smoothly along the back roads, following Barton on his Scrambler model. The engine sits in an old-fashioned double-cradle frame, with 41mm fork legs on the front, dual shocks with adjustable preload at the back. There is a single disc brake at both ends, and the front tire is 100/90-19, the rear, 130/80-17. The Bonneville is really a wonderfully comfortable machine, with a 30.5-inch seat height, and a nice flat saddle that a long-legged person such as myself can move around on. Weight is a little over 500 pounds, with 4.4 gallons filling the gas tank.

I will say that the suspension components on this ’09 Bonnie are more reminiscent of the old Meriden Triumphs than the new Hinckley triples; I realize this is all part of building down to a price. The shocks and fork work, and I had no qualms about bending this 50th down into a corner, but there is a lot of room for improvement. The only scuff marks I left on the bike were on the footpeg feelers, and I trust Mr. Bloor will forgive me my sins.

The museum was a delight, as was the freshly painted ’59 T120 and all the hundred other Triumphs on display. Most of the place burned to the ground a few years ago, but restoration artists all over the world have done great work, and the museum is again packed with bikes.

Museum shoot over, sun coming out, we headed off to more bucolic settings to shoot the 50th. We ended up photographing mostly around the historic Bosworth Battlefield, which was a bloody squabble that took place in 1485. This was where King Richard III was killed after he was thrown from his mount and supposedly cried out, “A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!”, that line made famous by Shakespeare in his play Richard III. Henry Tudor was the victor, and he declared himself Henry VII. That may be a much more sensible way to determine leadership rather than through this endless election process…I joke.

We spent the rest of the day shooting the 50th, having bangers and mashed for lunch at the local pub in Sheepy Parva, going down to the Ashby Canal with its riverboats for some scenic shots, and generally having a very nice day. As the light was fading, we had a look in Critchell’s computer to view his day’s work and saw we had some good pictures.

I imagine that many of these anniversary Bonnies will become instant collectibles, bought and stashed away in the hope that they will increase in value. A shame, really, as they should be ridden… that’s what the Bonneville was built for, half a century ago, as well as today. Buy yours, if you are lucky enough to find a dealer who has one, and put lots of miles on it. When you park it, passersby will stop to gawk and say, “What a good-looking motorcycle; I remember my uncle had one just like it.”