story and photography by Clement Salvadori

[This Triumph Bonneville T100 Cross Country Motorcycle Tour was originally published in the December 2006 issue of Rider magazine]

“How come you’re in Post?” he asks. Sensible question, as Post is not really on the main road to anywhere, and I am obviously an out-of-towner. Riding from Georgia to California, I tell him, mainly on two-lane roads, and crossing Texas on U.S. 380 seemed like a good choice. Which it is.

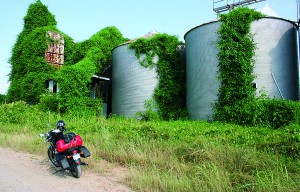

For a traveling rider like myself, the less traffic, the less congestion, the fewer people, the happier I am. And there is not much clutter along 380. Unless you count tens of thousands of acres of sagebrush, a good deal of dry farming, and a sprinkle of jack-pumps bringing crude oil out of the ground. Mostly it is just me and the two lanes of asphalt, where I can see 10 miles down the road, with nary a car in sight.

These are the Great Plains, part of that huge expanse of land that slopes gently down from the Rocky Mountains to the Mississippi River. No obstructions here; the highway engineers could just run a compass setting and go straight. On 380 the compass pointed due west. I like this sort of riding. Sure, given my druthers I would opt for curving roads through hilly country, but the reality of this great nation is that much of it is flat, and in traversing it a couple of dozen times over the years, I have come to enjoy this feature.

I am riding a new Triumph Bonneville, T100 variety, a bike which reminds me of my first long-distance treks 40-odd years ago when I was riding the old Triumph Bonnevilles and other British iron. Back then, in the 1960s, few interstate highways had been built, and riding from ocean to ocean meant a lot of two-lane roads. Those motorcycles were what we now call “naked” bikes, and doing a 3,000-mile run meant a lot of wind in your face.

Riding two-laners for long distances is very different from riding freeways and interstates. Load up your fully faired touring bike, hit the superslab, and you can run all day at 85, 90 mph in the fast lane—which seems to be the average speed in rural sections of these limited-access roads. But take U.S. 380 from Decatur, Texas, to Roswell, New Mexico, and you will get a real appreciation for America at its best. I thought, in my own mildly bizarre reckoning, that it would be an entertainment to repeat a two-lane trip, 40 years on. And what better bike to ride than on what Triumph calls one of its Modern Classics.

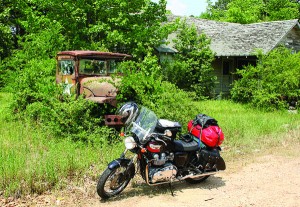

I flew into Atlanta late one evening, found my way to a motel in the suburb of Newnan where the corporate headquarters of Triumph USA are located, and in the morning the marketing manager, Monika Boutwell, picked me up. I had asked that a couple of accessories be mounted, like a pair of saddlebags and a tankbag. I also asked the Rifle company (which makes windscreens, not firearms) to send Boutwell a small ’screen (see What We Carried sidebar on page 50). Sign a few papers, and there is the black-and-red Bonnie, with 508 miles on the odometer, break-in maintenance done and ready to go.

I angle northwest from Newnan on two-laners, crossing into Alabama, heading for Birmingham and the Barber Motorcycle Museum, a mile or so off U.S. 78. After too few hours in the museum I must continue my trip. On the west side of the city this highway is four lanes of recklessly fast traffic, and after getting overtaken by a high-sided dump truck moving at 90 mph, I want to be gone from there. I head off onto AL 118, due west, which merges into U.S. 278 and crosses into Mississippi.

My paper map (if we’re going to do this ’60s-style, no GPS for us) indicates that MS 8, a two-laner, goes clear across the state, so I turn on that. Dusk is coming, and I am looking for a bed, which is to be found in Aberdeen at a Best Western. The B.W. also houses the only evening restaurant in town, which does leave something to be desired. Either my waitperson or the cook is not clear on the concept of medium-rare beef, confusing it with well-done, but since this has already taken the better part of an hour I let it slide. The manager does come over to apologize, explaining that she is coping with new staff. That was the only really flawed bit of cookery I encountered.

One of the joys of the two-laners is that there are few Denny’s at which to eat, and a whole lot of Mom & Pop diners. The coffee tends to be a bit weak, which is what happens when people drink coffee all day long, but the hashed browns come from real potatoes and the sausage is made locally. I ride into a little town and see half-a-dozen dirty pickups in front of a café, and that is where I eat. I can eavesdrop on the gossip, or more probably answer questions from old fellows in bib overalls who would like to know what it’s like to ride a motorcycle cross-country. “Easy as driving a pickup,” I say, “only it gets better mileage.”

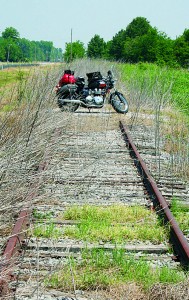

I’m riding through delta country, compliments of the Mississippi River, fertile soil, easily irrigated. Or, in the case of Katrina, sometimes over-irrigated. MS 8 takes me all the way to the Big Muddy, where I head south on MS 1, also known as the Great River Road. Along here the Mighty Miss is certainly not the sort of river that flows straight and true, but makes dozens of little loops, creating all sorts of navigational problems. The road, though, is straight and flat, right alongside an abandoned railway track.

I stop at the Winterville Mounds north of Greenville, a religious center that is the Mississippian Indian version of St. Peter’s Basilica. On this flat delta these mounds of earth stand out, which brings to mind the current religiousness of this part of the US of A, often called the Bible Belt. Every 10th building appears to be a Christian house of worship, Mount Carmel, Mount Zion, Bethel, Calvary, the Magnolia Baptist Church, the Blackjack Missionary Baptist Church—some solid, some shabby, all apparently standing empty six days of the week.

I cross the Mississippi River on a perfectly good two-lane bridge, aka U.S. 82, and I can see where a new bridge is being built half a mile downriver. Highway construction is big business in this big country of ours, and improvements are always in order. Zipping across Arkansas on U.S. 82, a two-lane road, running a comfortable 65-70 mph, Bonnie and I end up in Texarkana—a city that is way too big for our liking. A local directs us a few miles west to New Boston, where the Tex-Inn Motel welcomes us. I ask the proprietress where I might find a cold beer on this hot evening, and she announces mournfully that Bowie County is dry, which I am sure makes the whiskey-loving frontiersman Jim Bowie spin in his grave. However, as a gift to her thirsty client, she will be happy to give me a couple of chilled brewskis; very gracious.

I have all of Texas to cross, and a look at the map indicates we should continue on U.S. 82 to Gainesville, then angle southwest on Farm Road 51 to Decatur and pick up U.S. 380—which heads straight to Post. I plot my gas stops, as the T100 is a thirsty beast, getting about 35 miles to the gallon on a 4.4-gallon tank. I never quite trust the last 10 percent of a tank’s rated volume until I do a run-it-out test, which I have not done. I’m happy at 120 miles on the odometer, and use that as my fill-up mark. I do find that these grocery-store gas pumps do have one problem: nobody ever bothers to clean the top, where I like to put my helmet. AAA should rate gas stations on the basis of clean pump tops.

That night, 460 miles later, we end up in Post. Next morning we roll across open countryside, a formidable stretch for a lone horseman or ox-drawn wagon; the Spanish called this the Llano Estacado, or staked plain, due to the serrated mesa cliffs that can sometimes be seen in the distance. This uncluttered space would be a natural for any alien spacecraft looking for a landing zone, which may have already happened. At Roswell I take a leisurely look in the UFO Museum, and at the map. A U.S.-designated two-laner is fun, but I like to deviate onto even less-traveled roads, and NM 246 is 75 miles of untrafficked bliss, going around the north side of the Capitan Mountains, reconnecting with U.S. 380 in the little town of Capitan. That is the fun of the ride, heading where I need to go on the smallest roads. I see maybe 10 vehicles in those 75 miles.

After Capitan the road descends, passes the Malpais (Badlands) with its tumult of volcanic detritus, skirts the north edge of the White Sands Missile Range (where the first atomic bomb was tested) and then T-bones into Interstate 25 at San Antonio. Interstating north for 9 miles, we turn off at Socorro to connect with U.S. 60, another old two-laner heading west. Good road, climbing out of the Rio Grande River valley and crossing the Plains of Saint Augustine, flat, flat, flat for 20 miles. Which is where the National Radio Astronomy Observatory has set up its 27 giant dish antennas to eavesdrop on any aliens chattering in space.

We cross over the Continental Divide at 7,796 feet, and to celebrate I stop in Pie Town for a piece of Kathy Knapp’s lemon meringue pie at her Pie-O-Neer Café; her pie-making ability cannot be praised enough. I sleep in Quemado, waking up to a cool May morning at 7,000 feet, which turns to windy and cold as I enter Arizona. For me, a harsh quartering wind is worse than heat, cold, or rain. I turn onto AZ 260 in Show Low, which drops out of the wind as it goes down to Payson, a mainly four-lane road. At a big Circle K gas station, an attendant—cleaning the tops of the pumps, bless his heart—tells me about a motorcycle graveyard 10 miles south in Rye that I must visit (see Museums sidebar).

West out of Payson, AZ 260 reverts to its original two-lane status all the way to Camp Verde, where I visit Montezuma’s Castle, which is not a castle—and Montezuma never came near this place. To find out more, you will have to go yourself. At Cottonwood, Bonnie and I take AZ 89A going toward the old mining town of Jerome; this road eventually merges into AZ 89 north to Ash Fork, on Interstate 40. Five interstate miles west take me to Crookton Road, a part of old U.S. 66, the original two-laner. Great ride, 66, with little traffic and huge vistas, through Seligman and Peach Springs. Then it’s finally a bed at the Hill Top Motel in Kingman, with an excellent medium-rare T-bone at the Dambar Restaurant, right across the road.

Last morning. Old 66 runs crookedly to Oatman, then across the Colorado River to Needles, and I have to stay on I-40 for a few miles until exiting at Mountain Springs Summit and more old 66. The road is good through to Amboy, where the gas station has not operated in a long while, but from Amboy to Ludlow that two-lane pavement is rough and uncared for—because nobody but tourists use it. We skirt Barstow to the north on the old two-lane CA 58, then at Hinkley (remember the movie Erin Brockovich?) we have to get on the new 58 freeway, head across the Mojave Desert, climb up to Tehachapi Pass and drop down to Bakersfield. Crossing the San Joaquin Valley, America’s breadbasket, I come to McKittrick and the driveway to my house.

Except the driveway is 75 miles long, consisting of two-laners CA 58 and then CA 41, which are a delight to ride. For me, it is a relaxing way to end a trip, since I know all the turns and twists even better than the back of my hand. This is where the likes of a T100 shine, an unhurried rush through rolling countryside.

Two-lane America is very alive and very well. And a lot more entertaining than the freeways.

What We Carried

Any trip can be undertaken with nothing more than a credit card in hand, but I usually bring a little extra. I stuffed a few clothes into an Aerostich Dry Bag and asked Triumph to attach a pair of saddlebags and a tankbag from its accessory list, and I was set. Almost.

The last cross-country trip I took without any windscreen at all was in 1980, and since then I have come to appreciate having a small barrier between me and the elements. The Rifle company (www.rifle.com) makes a suitable ’screen called the SoloShield X, with superb hardware for attaching it to the handlebars. What I like about this 15- x 15-inch piece of clear plastic is that I’m not even aware of its being there, while it takes the wind pressure off my torso. It is a very clean and unobtrusive system.

Knowing that the T100’s total toolkit consists of one 5mm Allen wrench concealed behind the left side-cover, enabling one to take off the saddle and get at the owner’s manual, I thought I could use a little backup even though I did not expect anything to go wrong…and nothing did. Cruz Tools (www.cruztools.com) sent me its CruzMetrix kit to ease my fears. To which I added a large Stanley adjustable wrench because…

…I have a minor obsession about flat tires, as a nail can appear on any road, any time. Since the Bonnie has tube-type tires on spoked wheels, I would have to remove a wheel to fix the puncture. The rear axle is secured by a 24mm nut, which the toolkit did not have; hence the Stanley. I called up Stop & Go (www.stopngo.com) and had them send along the Deluxe Tube-Type Motorcycle Tire Repair Kit, which comes with three tire irons; fortunately, I never had the pleasure of using them.

Museums

The motorcycle graveyards.

When elephants get old they go down by a river where the grass is good and water nearby. After they die, the bones and ivory are washed away. Not so with motorcycles.

A lucky few motorcycles end up in museums, and the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum (www.barber museum.org), just east of Birmingham, Alabama, is one of the very best. Some 900 motorcycles and a few dozen cars are on display in this five-floor, 80,000-square-foot building. Pictures do not do the place justice. Technical curator Brian Slark spent three hours taking me around on his nickel tour, and I was impressed from beginning to end. I could go back and spend twice that amount of time admiring the machines, most of which are staged so the viewer gets a very good, very close view. The majority of them are restored, but a number are in as-found condition, with the original paint enhanced by the patina of age.

A lot of photos of the museum show those wonderful stacks of motorcycles, but those are more for decoration than information. Up close you can see a 100-year-old Belgian FN, an array of Vincent models, all the Honda V-4s grouped together, a great many Harleys and Indians. The displays are very well thought-out and accessible, the visitor being able to admire the instruments, see the drain-plugs. Go spend a day at this place; it is especially fun when motorcycles are racing on the track right outside the windows.

At the other end of the graveyard spectrum are places like All Bikes (928-474-2526), 1,700 miles due west of Birmingham in Rye, Arizona, a salvage yard where upward of 10,000 old motorcycles sit under the sun. These are all potential organ donors, and proprietor Rod Adler can get you that cylinder head for a 250 Adler (no relation), a rear fender for a Suzuki Titan or just about any other part you might conceivably need to fix an aged machine. Organization is admittedly chaotic, but Adler claims to know where everything is…which would qualify him for Mensa status. He is constantly packing off bits and pieces to the four corners of the earth, and as he slowly dismantles the bikes he has, lots more old motorcycles arrive at this resting place. He will never run out of parts.

Why 278?

by Dave Ekins

One of the options for Triumph’s newish Scrambler model, based on the Bonneville platform in the main story, is a pair of number plates inscribed with the digits 278. Why 278? Quite simply, this is the racing number of one of the most famous motorcycles in the world. One of four International Six Day Trials bikes ordered by Bud Ekins Motorcycles of Sherman Oaks, California, early in 1964 was the 1964 Triumph TR6SC in the photo. Bud formed the very first U.S. ISDT Silver Vase Team, which would never have made headlines except that actor Steve McQueen was onboard. Two TR6SCs and two TR5SCs were taken off the assembly line and sent to Triumph’s “Works Shop” for special Six-Day preparation. According to Hughie Hancock, the mechanic assigned to the bikes, Bud’s 500 (No. 278) and Steve’s 650 (No. 281) had some special engine work done while the other two remained standard.

Bud had taught Steve the unique technique of steering with the throttle, which is necessary when racing a 40-incher cross-country. The actor was good. Bud rode a 500 for the first time at this international level of competition and was running third in points when he broke his ankle. Steve also crashed and bent his TR6 too badly to continue, so the team effort was done. Cliff Coleman rode his TR6SC to win a gold medal and finished third among the open-class bikes. Yours truly, Bud’s brother Dave, forced his TR5SC to finish the Trials fifth in class and won another gold.

The following year No. 278 went to the Isle of Man for the 1965 ISDT. This time Ed Kretz Jr. was aboard, and the number changed to 295. The 1965 Six Days was the most difficult ever, and Kretz Jr. didn’t start the second day. Bud, myself and Cliff Coleman timed out at the end of the third day. Just 10 percent of the entries made the whole six days.

The four Triumphs came home to Sherman Oaks the following year, when Bud decided to make the first unassisted, timed race from Tijuana to La Paz. The four Silver Vase Triumphs were used, only this time Bud rode No. 281 and Eddie Mulder rode Bud’s TR5. Three bikes, minus Cliff, made it to La Paz within a few minutes of the time myself and Bill Robertson had set in 1962 riding 250cc Hondas—except Robertson and I were supported by an airplane with gas, food and maintenance.

Late in 1967 the National Off Road Racing Association decided to stage a 1,000-mile race from Tijuana to La Paz. Naturally, Bud and I rode No. 278. Bud had upgraded the fork and fitted a 5-gallon gas tank. During that race the bike demolished its suspension but still finished third.

Bud later sold the bike to Frank Danielson, who fitted No. 278 with a sidecar and won the sidecar class of the 1969 and ’70 NORRA Baja 1000. And threw in a Mint 400 win just for kicks. Danielson kept it in storage for 30 years. Then the Triumph was on display at the Petersen Museum for six months as part of a Steve McQueen feature. The numbers 278 and 295 are scratched into special Six Day paint blotches on the frame, and a third Girling shock was installed by Danielson for sidecar duty.

The bike is tucked away somewhere in a dark corner, but I can’t think of any other motorcycle that has been raced in five countries over a seven-year period by four AMA Hall of Fame members. Thirty-five years later the new Triumph has built a modern version, and No. 278 lives on.