We had experienced a little of Wyoming by riding through it on our way to and from Sturgis, South Dakota, one summer. We were struck by the beauty of Wyoming’s barren landscape, red rock and endless desert. It remains relatively undeveloped, which allows you to see the Old Wild West in its original form.

Traditionally Wyoming is a state people cross but don’t usually stay in. This has been true since America’s earliest days. The state’s total population is less than a half million, yet the four major pioneer trails—the Oregon, California, Mormon and Pony Express—all traverse its unforgiving landscape. In many places the trails join, and you can see the wagon ruts and landmarks that told the pioneers they were heading west.

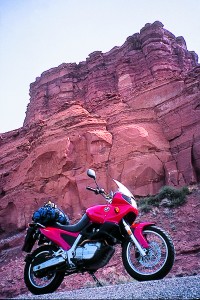

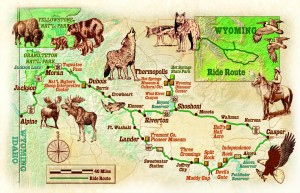

To get to know the Equality State better and to learn some of its history, we made a loop between Jackson and Casper. We took our time. In fact, we took two years to do the entire round trip of about 600 miles. One year we made a northern run to Thermopolis while riding identical Honda Transalps from Idaho to the East Coast. The following year, we made a more southerly crossing. That time I was riding a 1997 candy-apple red BMW F650 I’d just picked up in Omaha with 700 miles on it. My riding partner took his Yamaha TDM and met me at the border between Wyoming and Nebraska.

Two cautions: First, if you’re planning a spring journey, be sure to time it right. Go too soon and the high mountain passes will be snowed in. Leave too late and the desert heat and winds will parch your lips and scorch your bike’s tires. Depending on the temperature and late snowmelt, mid-May to mid-June is a good window for seeing the state on two wheels. Second, gas-up whenever you can. As they like to say, you know you’re in Wyoming when wide-open spaces mean 120 miles between gas stops.

Magnificent Mountains

We started at a friend’s house near Alpine, Wyoming. From there, it’s about 60 miles northeast along the Snake River to Jackson, which is nestled at the base of the Grand Tetons. I’m always glad to see the Tetons; their craggy magnificence lifts my spirits. But even though Jackson has a Western flair and is filled with cute shops and restaurants, it’s touristy and Wyoming natives tend to avoid it. They say that Jackson is about as much like Wyoming as Disneyland.

The town’s many hotels and motels tend to book up on weekends, so we usually stop for a meal at Bubba’s (great barbecue) and to watch the daily gun fights held for tourists in and around the town square. Then we saddle up and head north and east on Highways 191 and 26/287 to Dubois, where you can find real cowboys competing for big money on the rodeo circuit during the summer. You know you’re in Wyoming when the rodeo is the social event of the year.

Buffalo and deer graze along the highway as it climbs to 9,600 feet over the Continental Divide at Togwatee Pass. If you’re lucky, you might spy a moose or two. There’s lots of snow at the summit, even in mid-June. You know you’re in Wyoming when you keep your snow tires on until June. Hotels in Dubois also get booked up in summer. We’ve found that Pinnacle Peak, a motel to the west of Dubois owned by the family that developed Jardine exhaust systems, is a good option. If it’s full, you can pitch a tent in the campground to the rear, as we did. As I nodded off to sleep, I heard coyotes howling—or were they wolves?

Good food can be had at Bernie’s Café or The Really Wild Bunch Grill & Barn in Dubois. Another stop might be to see Tom Rose, a Royal Enfield dealer on the east side of town. The scenery changes to desert and it gets hot on the way to Thermopolis, our next stop. Fortunately, a local sheriff told us about a shortcut that skirts Riverton and continues into Shoshoni, the last town you’ll encounter before Highway 20 veers north into the scenic Wind River canyon.

High Winds

A few words about Wyoming winds: No matter which direction you’re headed in this state, you always seem to encounter strong head- or sidewinds. Stiff breezes buffeted us as we passed Boysen Reservoir and descended into the 10-mile-long Wind River canyon. And we encountered ferocious winds that blew us from side to side between Muddy Gap and Lander on Highway 287 West during our return to Jackson.

The Wind River canyon can make travelers feel insignificant. The river has cut 2,500 feet into the canyon, exposing a billion years of geology—Paleozoic, Precambrian and Cambrian rock. You’ll pass through three tunnels carved into the rock before the canyon ends with a stretch of red Triassic beds just south of Thermopolis.

Thermopolis’ claim to fame is the Big Spring, supposedly the largest mineral hot spring in the world. The spring was located on Shoshone and Arapaho land, but naturally, the U.S. government wanted to buy it. Fortunately, when signing over the land, Chief Washakie of the Shoshones and Chief Sharp Nose of the Arapahos insisted that a portion of what they called Bah-gue-wana or “Smoking Water” should remain free to all people. In other words, it was because of the foresight of these two chiefs that we could soak for free in the Wyoming State Bathhouse in Hot Springs State Park.

Soak but No Soap

The public bathhouse offers a choice of indoor or outdoor pools or private tubs in the changing rooms. The Big Spring water bubbles up out of the ground at 127 degrees F and cascades over descending terraces of built-up mineral deposits and cooling ponds before it accumulates at a bearable 104 degrees F in the bathhouse pools and two nearby commercial water parks. The kids can have the slides—we sore and weary riders chose to soak free in the rejuvenating waters for 20 minutes, the maximum time allowed. Soap and shampoo aren’t permitted, even in the showers, which use the hot mineral water as well. Bathing suits and towels are available for rent.

The state park is an interesting jumble of sights, from the Terrace Walks around the descending mineral waters, to the historic Swinging Bridge, first built in 1916 to connect the main spring with the Fremont Spring on the opposite bank of the Big Horn River flowing through town. Traveling here takes you back to a more innocent time when everyone piled into the car for a family vacation. Even the restaurants in town are mostly 1950s-style hamburger and ice cream joints—with low prices as well.

The Fountain of Youth RV Park boasts the second-largest natural hot springs swimming pool in the world. With our tents pitched and sleeping bags waiting, we paddled in the calming warm waters and watched the stars come out, then slept like babies.

There isn’t much to say about Highway 20/26 between Shoshoni and Casper. It’s hot, dry and was under construction when we rode through. You know you’re in Wyoming when Hell’s Half Acre looks like Hell’s Half Acre.

Plucky Pioneers

After Casper, things turned greener, thanks to the rains during the months prior to our trip. “I haven’t seen it this green before without my sunglasses,” a vacationing state resident told us at breakfast. At this point we were ready for some pioneer landmarks, so we set out west on Highway 220. This road serves as living testimony to the courage of the early settlers. As you retrace their steps on the historic trails, you wonder how they managed to get their ox-and-wagon teams over the desert, and quickly realize how motivated they were to become homesteaders.

Fifty-seven miles west of Casper, we came upon Independence Rock, the first landmark the pioneers spotted in the desert. The smooth monolith gets its name from being located halfway between the Oregon Trail’s start at the Missouri River and its finish in Oregon. The plucky pioneers tried to arrive here in time to celebrate Independence Day on July 4. This meant they’d make it to Oregon before it snowed in the Rockies. About 50,000 settlers were believed to have carved their names into the smooth rock (or paid $5 to have their names carved).

A few miles west we spied the second landmark, Devil’s Gate.

The Sweetwater River made this short, narrow can-yon where the Indians thought an evil creature once lurked, hence its name. To the settlers, though, the shade and sandy banks of this waterhole made it a welcome rest stop. The third landmark still further west is Split Rock, a V-shaped notch resembling a rifle sight in one of the Granite Mountains.

Cowboys are alive and well in Wyoming, and it was great to see some of them roping and branding calves in corrals by the side of the highway. Nowadays they sometimes use ATVs and other modern equipment. We even saw a rancher herding horses and cows by helicopter.

You know you’re in Wyoming when antelope outnumber the sheep. These delicate animals are everywhere, and three of them sprinted across the highway just ahead of us. Antelope can’t jump fences, so they found an opening in a fence by the road and scurried under it.

A Modern Ghost Town

We turned on the throttles as we headed west on Highway 287 at Muddy Gap, but trucks still passed us. You know you’re in Wyoming if you get passed while riding 75 mph. We hadn’t gassed up since Casper and had been fighting a headwind, so we began to worry that we’d run dry in the desert. Jeffrey City, the next town we’d pass, seemed a likely place to get a fill, and we were glad when we came to its outskirts and saw a Texaco sign.

But the station was closed, just like everything else in this burg. Jeffrey City is an eerie sight: a modern-day ghost town. The town sprung up to support uranium mining, but its residents appear to have moved out overnight after the mines closed. You know you’re in Wyoming when the boom town boomed yesterday.

A lonely gas pump was a welcome sight up the road at Sweetwater Station Junction and the motorcycles were thirsty. We were, too, so we had a soda in the bar with a few locals. Soon after we arrived in Lander, which is thriving and filled with interesting public art. Our next stop was the Indian Trading Post store at Fort Washakie. Turn south on Trout Creek Road in Fort Washakie, and you’ll come to Sacajawea’s Cemetery. A larger-than-life bronze statue of the Shoshone woman who served as Lewis and Clark’s guide presides over the cemetery. Sacajawea and her son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau have graves in the cemetery. However, Charbonneau is buried in Oregon, where he died during a trip. His grave there is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The BMW had plenty of pep on the way back through Dubois to Jackson. It had been garaged for six years and apparently was rarin’ to go. We had gotten acquainted during the 1,100-mile journey west from Omaha and now it was time to head home. We crossed over the Continental Divide and as the sun was setting, the Grand Tetons came into view and lifted my spirits once again.

(This article Roaming Wyoming was published in the September 2004 issue of Rider magazine.)