My buddies had deserted me to go for a ride in the European Alps, so I decided to visit “America’s Alps” on a trip through the heart of Idaho. Riding alone through the Gem state’s solar plexus for three days and 750 miles, I would set my own pace, stopping when I wanted, answering to no one.

I had bought a BMW F650 in Omaha a few weeks earlier, but the roads home from Nebraska were as straight as bowling alleys. On this getaway, my new motorcycle was going to show me what it could do on mountain roads that switched back on themselves.

By heading into the mountains, I’d also be getting out of the heat in Boise, which had been simmering at 95 degrees or more for days on end. America’s corporate titans were having their annual meeting at the famous Sun Valley Lodge near Ketchum that weekend, too—maybe I’d run into Bill Gates or Warren Buffet and catch a few stock tips.

Wrong on both counts. The heat clung to me like a lost puppy, even while crossing summits of 8,000 feet or more. And I never ran into Warren or Bill—the Sun Valley Lodge was ultra-protective of the big-wigs’ privacy. But the executives made their presence known regardless. When I passed the Hailey airport, which serves the Sun Valley resort area, about 20 or more Gulfstream and other corporate jets waited on the tarmac.

My journey started on Highway 21, a favorite of Boise riders, especially on weekends. Packs of cruisers run the 38 miles to Idaho City, sometimes looping back to Boise through Lowman and Banks. Two-lane stretches allow for easy passing, and the ample curves make everyone feel like they’ve had a good ride.

Unusual sites dot the roadside, including the Boise Diversion Dam, which was completed in 1909 so water from the Boise River could irrigate the fertile land and its famous Idaho potatoes. Next, the highway winds around the 340-foot-high Lucky Peak Dam. After that, things get curvy. I decided to count the turns from Lucky Peak Reservoir to Idaho City. I’d include only those curves that required a lean; “S” curves counted as one, unless each part of the “S” was really extreme. I reached 45 before hitting the outskirts of Idaho City.

This is a town well worth exploring. Gold was discovered near here in 1862, causing the biggest gold rush since the ’49ers raced to California. Idaho City grew to 6,200 residents, becoming the largest city in the Northwest—larger even than Portland, Oregon. The miners lived in an atmosphere of lawlessness—supposedly, only 28 of the 200 people buried in the town’s first cemetery died of natural causes.

Although Idaho City burned down four times, its historic buildings, including several that housed Chinese businesses, are some of the most well-preserved 1800s structures in the United States. If you’re coming by here early, stop for breakfast at Trudy’s Kitchen, which serves large portions and has great antiques lining the walls.

The best of Idaho 21, also called the Ponderosa Pine Scenic Byway, was yet to come. Between Idaho City and Lowman, the road makes dozens of hairpins and switchbacks as it ascends and descends Mores Creek Summit (6,118 feet) and Banner Ridge (7,056 feet). Again, I decided to count the curves. I may have lost count, but I tallied 66 between Idaho City and Lowman, for a total of more than 100 in the 78 miles I’d ridden since leaving Boise.

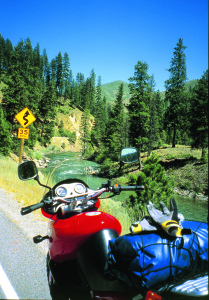

I stopped for a soda at the Sourdough Lodge, and then at a scenic overview for my first glimpse of “America’s Alps”—actually, Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains. This range is a miniature version of the Grand Tetons, but my view from the south was a meager preview of what was to come. Still, Idaho was wearing her best clothes for me. Highway 21 follows the South Fork of the Payette River, and it was flowing turquoise from the snowmelt. Yes, snow remained on the Sawtooths, even in July.

Eagles, hawks, fox, elk and deer are common along this stretch. Certainly, there’s more wildlife than cars. The mountains loomed larger as I approached Stanley, a crossroads where every building seems to consist of logs and antlers. It’s known as the gateway to the largest roadless wilderness in the lower 48. Here tourists leave for raft trips on the Salmon River—the “River of No Return.”

Stanley is the only place in the United States where three National Scenic Byways converge: The Ponderosa Pine, the Sawtooth and the Salmon River. My trip would take me on all three. I turned onto Highway 75—the Sawtooth Scenic Byway. Each mile brought a new view of these great mountains as I headed south to Ketchum for the night.

I crossed the 8,200-foot Galena Summit and descended into town, a Mecca for the rich and famous and home of the Sun Valley Resort. Good places to eat include The Pioneer Saloon, where the wealthy folk go and everything is prepared on a grill, like the less expensive Ketchum Burrito (a burrito the size of your forearm for $7.75).

The next morning, the sun lit up the runs on Bald Mountain, Sun Valley’s premier ski mountain. It was considered too steep for U.S. skiers and the resort builders didn’t develop it initially, preferring some smaller hills nearby.

I moseyed around the Sun Valley Lodge looking for corporate moguls; alas, all I saw was a Harley owned by one of Idaho Governor Dirk Kempthorne’s bodyguards. After stopping on Sun Valley Road to admire three stately sculptured bulls, part of a set of eight by artist Peter Woytuk, I opted to skip breakfast with the beautiful people in Ketchum in favor of more blue-collar Hailey farther south on Highway 75. Tip: Don’t miss the Hailey Coffee Co. on Main Street for great java and baked goods.

Locals heading east take the Gannett Cutoff at Bellevue to Highway 20 near Picabo, the town that gave ski racer Picabo Street her name. Silver Creek crosses the highway several times. Ernest Hemingway, another famous Idahoan, used to fish for trout in Silver Creek, considered the crème de la crème of Idaho fly-fishing holes.

As I rode eastward, farm fields changed to craggy rocks, an indication Craters of the Moon National Monument was nearing. This 83-square-mile black lava and basalt terrain on the plains of Idaho is so forbidding—and so like the moon’s surface—that NASA tested the Moon Rover here. A ride on the seven-mile loop road through the monument ($5) is worth taking. You can stop and hike around eerie Devil’s Orchard or peer into the Snow Cone, which holds snow year long, despite outside temperatures well above 100 degrees in summer.

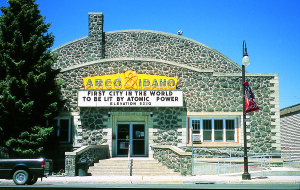

Farther east, Highway 20 runs into Arco, the first U.S. city to be lit with power from an atomic reactor. The BMW ran at top speed as it approached Arco because I was ready for lunch at Grandpa’s Southern Bar-B-Q, a soul-food restaurant serving ribs, turnip greens, pecan pie and “swamp water” (strawberry ice tea).

I didn’t want lunch to end because I knew what awaited: miles of high desert. My route led northeast on Highway 22/33 to Howe and then to the junction with Highway 28. Alone in the desert and no cars in sight, I wished I had stuck to the buddy system. What if I ran out of gas or the bike quit on me? The narrators of those TV nature specials say life is abundant in the desert. No way. I felt certain I was the only living thing out there.

Reaching the T-intersection with Highway 28 was a relief. I let three Harley riders pass, then joined their formation for miles. It was good to see people again. This road is designated the Sacagawea Memorial Highway because the region is the birthplace of Sacagawea, the Shoshone teenager who led Lewis and Clark’s expedition through the mountains to the Columbia River, probably saving their lives.

The Lemhi and Beaverhead mountains flank this road, which leads to old silver and lead ore mining towns. These settlements came and went. Gilmore at milepost 73 is a ghost town, while Leadore, with only 93 people, is at risk of becoming one.

I schmoozed with locals in the Silver Dollar Café in Leadore, then continued north to Tendoy. Next to the Tendoy Store, look for the start of the Lewis and Clark National Back Country Byway and Adventure Road, a single-track 39-mile gravel loop to Lemhi pass, where Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery entered Idaho from Montana. The pass is a National Historic Monument and has been attracting visitors as the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial celebration picks up momentum. Sections of the road are steep, but a dual-sport can handle them easily.

My BMW was up to the job, but I’m saving this journey for another day. Soon I was in Salmon, where a visitor center dedicated to Sacagawea is under construction and expected to open in 2004. The heat pursued me; it was 105 degrees at 6 p.m. and shortly after turning on Highway 93, I took refuge in the air-conditioned Burnt Bun Restaurant.

Highway 93 follows the Salmon River. Twelve miles south, the Greyhouse Inn Bed and Breakfast was a welcome sight. This Victorian building was once a hospital in the town of Salmon and was trucked to its current location in the early 1970s. I was so hot I wanted to jump in the Salmon River; without hesitation, the inn’s owner Sharon Osgood drove me to a local swimming hole where the temperature was just perfect.

I said good-bye to the Osgoods early the next morning. It was wonderfully cool—finally!—as I pulled out onto Highway 93 toward Challis. I was now on the Salmon River Scenic Byway, which follows the Salmon. The view improves at every turn. You’ll pass the caves that mountain man “Dugout Dick” Zimmerman has dug into the hillside. If you see him sitting outside in the sun, give him a wave. If you’re really hardy, you can rent one of his caves for a few bucks and spend the night.

I counted three sandhill cranes flapping above the river as the canyon walls turned colors in the morning light. The byway leads to the “Land of the Yankee Fork.” In 1879, prospectors found gold in this Salmon River tributary, causing another rush of miners and more ghost towns. An interesting museum about the period is located at the intersection of Highway 93 and 75.

It’s hard to decide which way to go at this junction, because both routes are a treat for riders. I chose to continue west on 75 to Stanley. Several hot springs bubble along this stretch, including one near Sunbeam that has a bathhouse. I didn’t stop because I wanted to get to Lower Stanley in time to see the eastern sun on the Sawtooth Mountains. When America’s Alps came into view, I felt like I, too, was riding in Europe.

(This article The Alps of Idaho: Fleeing the heat for some cool curves was published in the March 2004 issue of Rider magazine.)