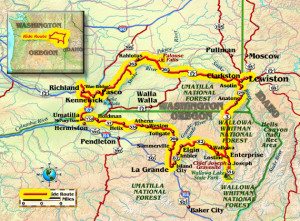

Whenever possible, I like to take a longer, more scenic route between La Grande, Oregon, and Richland, Washington, than my regular Interstate commute. Two of these routes make a nice 2-day, 500-mile motorcycle odyssey through the tri-state region of Oregon, Washington and Idaho. By April 25, it is finally warm enough to cross the passes without much risk of a sudden snowstorm.

Leaving La Grande, I ride northward on Hunter Road and eastward on McKenzie Lane, at the foot of still-snow-crested Mount Emily, to the small town of Summerville. The sight of hundreds of migrating birds slows my pace as I continue northward on Summerville Road, past pastures, ponds and snowmelt-swollen streams.

The road tees just west of Elgin, onto State Route 204, and I turn here toward Tollgate. Rising terrain soon presents deep snow on either side of the highway—no side trips onto back roads today! Reaching the Blue Mountains summit at an elevation of 5,158 feet, I ride to Spout Springs Ski Area, which is closed for summer, but still has plenty of snow for cross-country skiers. A couple of miles later there’s the still-frozen Langdon Lake and snowbound cabins near Tollgate, a tiny town named for its toll collections from wagon traffic.

The terrain now drops toward the fertile Palouse, a vast dry-land agricultural region in northeastern Oregon, eastern Washington and western Idaho, where a local phenomenon creates a geologic wonder of the world. The landscape is young, as flowing lava inundated the area only a few million years ago. Glaciers later pulverized much of the new hardpan and warm winds drifted the new soil, called loess, into dunes as large as those of the Sahara. The hills now produce bumper crops of grain, but much of the Palouse was washed away more than 10,000 years ago by the epic Missoula Floods. The high ground remained untouched, but much of the flood zone is now called the Channeled Scablands.

Descending the Blue Mountains onto the Palouse, I skirt past Weston (a town of significance to the Lamb Weston potato company) and ride through the farming community of Athena, known for its annual Scottish Highlands Festival in July. Next comes Helix, a town smack in the middle of the Palouse, surrounded by loess hills and farm equipment hard at work. Roads are never straight or level in the Palouse, a fact appreciated mostly by riders who enjoy the curves. The hills are a couple-hundred feet high, on average, or several times that height where streams cut through. Many tractors and combines have rolled over; in fact, the town of Palouse, Washington, is at least semi-famous for developing farm equipment that keeps the cab level and the center of gravity low.

Turning onto Oregon Route 37, I reach Holdman, a town at the junction of two narrow hollows now consisting of a handful of houses, a grain elevator and an abandoned schoolhouse. Approaching the Columbia River, the landscape becomes a transition zone—some Palouse, some Channeled Scablands—it all depends on how high the waters came during the great floods. Some floods came higher than others, and some hills remain rounded on one side and ripped vertically into bedrock on the other. But by the time I descend into the Columbia River Valley proper, it’s all rip-and-gouge. That’s what Lewis and Clark saw where I turn onto U. S. Route 730; in fact, their journals note a significant rapid just downstream from Wallula Gap, a bottleneck in the river that backed up water to a depth of several hundred feet during the floods.

Continuing to McNary Dam, the fourth of 11 U.S. dams on the Columbia River, the lake behind it extends to Richland, Washington, above which lies the 40-mile Hanford Reach. This stretch, plus the 90-mile, mostly estuary, section below Bonneville Dam, comprise the only remaining free-flowing parts of the river within the U.S.

Turning onto Interstate 82 at Umatilla, I cross the Columbia River into Washington just below McNary Dam. The nearby Umatilla Army Depot became a safer place in 2011, when the incineration of an arsenal of nerve gas was completed, but hundreds of pimple-like storage bunkers still dot the landscape. On I-82, I pass another clean-energy development: wind. The region receives a steady and brisk wind, and wind turbines rise like needles from an urchin.

Arriving in Richland, there’s just enough daylight remaining to perform some overdue spring yard work. Richland is headquarters to the Hanford Site (formerly Hanford Nuclear Reservation), where plutonium was long produced for nuclear weapons, including the infamous bomb dropped on Nagasaki. The site no longer produces weapons, and management has passed from the Department of Defense to the Department of Energy for cleanup and for development of clean energy and energy-conservation technologies.

Next morning, I depart on a somewhat-longer route back to La Grande. I ride through Kennewick to take care of some business and then cross the “Blue Bridge” (officially the Pioneer Memorial Bridge) on U.S. Route 395 into Pasco. Just upstream of this bridge, the Columbia River hosts annual hydroplane races, where boats reach speeds of more than 200 mph.

Following U.S. Route 12 for a few miles and exiting onto Pasco-Kahlotus Road, I take a couple of side trips to the Snake River to view the dry washes, carved over eons of gradual erosion, that did not become coulees (box-shaped canyons formed by floods) during the Missoula Floods. I see a tugboat pushing its load toward Portland, gaze at Lower Monumental Dam and Lock, and ascend back to Pasco-Kahlotus Road through Devil’s Canyon, a dry wash that suddenly became a coulee when floodwaters spilled over the banks of Washtucna Coulee at Kahlotus. Washtucna Coulee was the main channel of the Palouse River, which roughly paralleled the Snake River toward its own confluence with the Columbia River, until spillover about 40 miles upstream from Kahlotus ripped a new channel to the nearby Snake River and created Palouse Falls. This beautiful 200-foot waterfall attracts lots of visitors and more than a few motorcycles.

After viewing the falls, I descend to the confluence of the Palouse and Snake rivers, ride under a high railroad trestle, cross the river on a parallel highway bridge, and continue to Starbuck. Turning onto U.S. 12, there’s a group of wind turbines at Dodge, and I ride through historic Pomeroy before reaching the west’s farthest-inland port at Clarkston, Washington and Lewiston, Idaho. Named after William Clark and Meriwether Lewis, who passed through here in 1805 and again in 1806, these cities host a bustling port that loads grain, logs, paper and other freight onto barges bound for Portland.

Following Washington State Highway 129 through Asotin, the highway begins a twisty 2,000-foot climb out of the canyon. I am tempted to stop at the Asotin County Fair, but I press on in order to reach La Grande before dark. Just south of Asotin, the Snake River and its major tributary, the Salmon River (the “River of No Return”), carve out Hells Canyon, the deepest canyon in North America. At a depth of nearly 8,000 feet, it vertically eclipses the Grand Canyon by about 2,000 feet. Road access to Hells Canyon is limited to overlooks and dead-end roads, while today’s through-route skirts the western rim and offers dramatic views of tributary canyons.

Past the Rattlesnake Mountain summit, the road follows a narrow gulch for a short distance before popping out into a breathtaking expanse of switchbacks that drop into the deep Grande Ronde River canyon. Famous for its twisties and fantastic views, this is one of America’s most-publicized motorcycle rides, and for good reason. Several photo stops later, and several-thousand feet lower, I cross the Grande Ronde River at Boggan’s Oasis and begin the long climb out of the canyon. The highway becomes Oregon Route 3 at the state line. A few miles farther south, the Joseph Canyon overlook affords another view into a deep canyon.

The road begins a gradual descent into the lush Wallowa River Valley, with its backdrop of snowcapped peaks. From this valley in 1877, Chief Joseph and his band of Nez Perce fled for Canada while the U.S. Cavalry pursued in a campaign to confine the band onto a reduced-size reservation outside its homeland. The ensuing 5-month, 1,170-mile chase included skirmishes, a diversion to Yellowstone and a dash for Canada that ended in Montana, near the Canadian border. Surrounded, outnumbered, outgunned and with his band greatly reduced by battle and the elements, Chief Joseph tendered his surrender, culminating in his now-famous words, “From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

At Enterprise, I ride toward Joseph on State Route 82, a popular loop route of the annual Hells Canyon Motorcycle Rally, based in Baker City and nicknamed “Sturgis Light.” A few miles later, I ride into the beautiful, artsy, touristy town of Joseph, named in honor of the aforementioned chief, whose bronze likeness now adorns Main Street. The town hosts many annual events, including Hogfest, where motorcyclists gather at places like the Stubborn Mule Saloon & Steakhouse for live music and local microbrews.

Just past town, I pull off adjacent to majestic Wallowa Lake to pay my respects at the gravesite of Old Chief Joseph, father to Chief Joseph of the previous story (the younger Chief Joseph is interred at Nespelem, Washington, near the Grand Coulee Dam). Wallowa Lake backs up into a glacier-carved canyon, where a moraine of rocks and silt dropped from a receding glacier holds it back. After soaking in the view, I begin the final leg of my journey, back through Joseph and Enterprise, then through Lostine and Wallowa, past the confluence of the Wallowa and Minam rivers and through the beautiful towns of Elgin and Imbler.

I’m back on the Oregon Trail as I approach Island City and La Grande, avoiding that old wagon road (a.k.a. Interstate 84) on this outing. As the saying goes, “I took the road less traveled”—a 500-mile loop through fantastic scenery steeped in western history and with abundant twisties. It just doesn’t get any better than this!

Good article on Pacific Northwest Odyssey, Oct issue. What is driving me crazy, is the bike in the article. What is it, a custom? I like the design of the complete bike. —thank you —Ray—

The bike is a Suzuki Intruder 1400——late ’80s, early 90s. We can probably track down the exact year if you’d like.

Suzuki Intruder (Boulevard) VS800 (not 1400) Is the “factory custom” bike.