Here’s what I took away from three weeks on the road, from Arkansas to the middle of Baja, California: You really have to want to see the whales.

By the time I logged the 1,500-plus miles between my home and La Mesa, California, to rendezvous with my group in March 2014, I’d been battered by a headwind from hell and frozen nearly solid in Texas. Even being at the starting line of this trip was a victory—the night before departure, my KTM 950 Adventure almost went up in flames due to a melting electrical connector. When I finally did manage to get under way, I only made it to my first gas stop before being turned back by an ignition key broken off in the gas cap.

I persevered because I’d made the trip before, and know Baja is a world-class motorcycle destination, even if you never leave the pavement. The food is fresh and cheap, the roads are good, the spring weather is warm, and there is no other place where you can get up close and personal with a whale without getting wet.

This time we were 11 riders on 10 bikes: five KTM Adventures, two BMW R 1200 GS models, one Triumph Street Triple, one Triumph Tiger and one Kawasaki KLR650. After we met, we took California Route 94, a.k.a. Campo Road, south from La Mesa to the border crossing at Tecate, bypassing the chaos of Tijuana and the storm-damaged Mexican Highway 1, a chunk of which slid into the ocean just north of Ensenada in 2013. Our route, Highway 3 from Tecate to Ensenada, is called the Ruta del Vino, or the Wine Road, because it winds through a scenic region nicknamed the Napa Valley of Mexico. The asphalt is as smooth and flowing as any you’ll find north of the border.

We only covered 80 miles the first day. Les Martin, our leader and owner of the touring organization Motortreks, has been riding on- and off-road in Baja for decades. He knows it’s prudent to take it easy after crossing the border because you need time to get into Mexican riding mode. The rules down there are simple: Do what you want (within reason), but don’t hit anyone. Speed limits are suggestions, but there are hazards here you simply don’t see in gringolandia: cows that blend with the scenery, cars abandoned in mid curve, diesel fuel spills across both lanes, etc. On a previous trip, I passed a guy rolling a dead mule, stiff legs sticking straight in the air, down the road with traffic backing up behind him. You just never know.

We made it to Ensenada early and celebrated our first day in Mexico with plastic cups of street ceviche, a spicy brew of fresh octopus, sea snail, fish and clams straight from the nearby Pacific.

Points South

For day two, our destination was Cataviña, about 235 miles south. After breaking free of the string of small, dusty towns between Ensenada and Lárzaro Cárdenas, Highway 1 follows a lazy hook in the coastline that brings the Pacific back into view. The character of Baja changes here, from industrial/agricultural to wild and scenic. At last a sense of the peninsula’s open spaces and endless coastline appears.

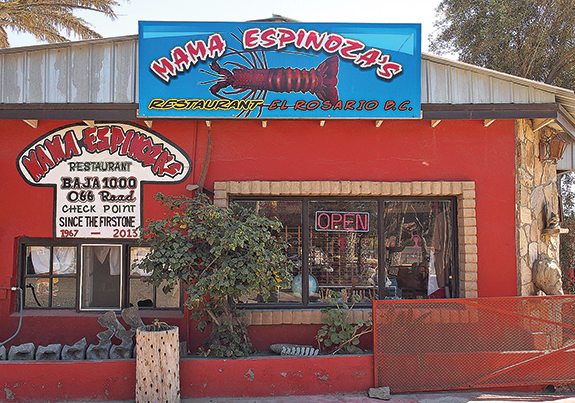

Eventually the highway jogs inland again, passing through El Rosario. We stopped for lunch at Mama Espinoza’s, a Baja landmark since Anna Grosso Pena opened the doors of her home in 1930. Mama’s has been a hangout for Baja racers since 1967 when it was the first checkpoint in the inaugural Baja 1000. It’s an off-road racing museum, and the food ain’t bad either. You can’t go wrong with the caldo de jaiba (crab soup), served with homemade beans and fresh tortillas.

From Mama’s we rode past fields of cilantro and peppers and up the Devil’s Backbone, a two-lane rollercoaster that follows the crest of the mountain range dividing the peninsula. The road is so steep in places that large trucks often stall on the uphill climbs, unable to pull the grade. When that happens, traffic swings around the stalled trucks, meaning riders could be carving through a blind curve with a steep drop off, only to find both lanes blocked. Luckily, all we came across was smooth asphalt. Les coached us on proper apexing the night before, and our group was riding tighter and safer as a result.

Descending from the Devil’s Backbone, the rolling hills changed from brown to green and then disappear altogether, replaced by a topsy-turvy topography of house-sized boulders stacked at crazy angles and cacti that look as though they were inspired by Dr. Seuss.

Cataviña is just a wide spot in the road, but travelers know it as the only gas stop for 100 miles north or south, and as the home of the Hotel Mision Cataviña, a state-run desert refuge of polished wood and red brick, expansive courtyards, lush landscaping and surprising elegance. The hotel seems out of place in its surroundings, and it’s all powered by a generator the size of a locomotive that thrums through the quiet night like an idling semi truck.

We bought gas from a roadside entrepreneur who hauls it in the back of his pickup in 55-gallon drums, and then settled into our rooms. Night comes slowly out here. Stars winked on—the sky is dark and reliably cloudless—and talk around the pool turned to moto tours past, present and future. After a few cervezas, we filled a table in the hotel’s dining room and enjoyed chicken mole, shrimp cocktails and fish tacos before returning to clean rooms and soft beds.

Day three was our final push south, 245 miles to San Ignacio. This wasn’t the best riding of the trip; the landscape flattens out near Guerro Negro, an industrial clump Les dubbed “the Bakersfield of Baja.” Guerro Negro is known for ospreys that nest on its power poles, as a whale-watching destination, and as the headquarters of the largest evaporative salt mining operation in the world. It’s often foggy and cold, in stark contrast to the desert heat.

San Ignacio, in contrast, comes as a sleepy surprise. It’s a swath of green nestled in a lush valley fed by an underground stream that emerges near town, flows about a mile, and disappears back into the ground. The stream waters acres of date palms planted by Jesuits who built a mission here in 1728. The Jesuits were booted out of Mexico in 1768 and Dominican missionaries built the church that dominates the center of this small town in 1786.

Our home for the next three days was Ignacio Springs Bed & Breakfast, a palm oasis on the banks of Rio San Ignacio. Some of us stayed in cabins, others in spacious canvas yurts. Terry and Gary Marcer, transplanted Canadians who’ve run the B&B since 2001, were our hosts. We enjoyed home-cooked meals served family style and nights on the patio petting local dogs and drinking large, sweaty bottles of Pacifico beer. We fished off the dock, kayaked in the spring and napped in the shade of this unlikely ribbon of green in an otherwise brown landscape.

Whale of a Day

It’s an easy 25-mile ride to San Ignacio Lagoon, where we were issued wristbands and lifejackets and sent down to the water for the first of two two-hour trips aboard 20-foot, outboard-powered boats called pongas.

Eastern Pacific gray whales travel 6,000 miles south, from the waters off Alaska—the longest annual migration of any mammal. On arrival, the males patrol the mouth of the bay for sharks and orcas while the females give birth. Mothers and babies seem to take a keen interest in human visitors, with the mothers often nudging their calves right up next to the boats, allowing people in the boat to rub the baby’s snout. The whales swim from boat-to-boat, rolling over for belly rubs and

spraying us with blasts from their spouts. Whale snot, it turns out, is tough to clean off your camera lens.

Considering the history of interaction between humans and whales, it’s amazing these gentle giants want anything to do with us. Eastern grays were hunted to near extinction in these waters in the mid 1800s. But they’ve been protected since 1949 and have made a comeback. Our guide told us there were about 1,600 whales in San Ignacio Lagoon in 2014, a particularly good year.

Les put an extra day in the schedule in case of bad weather, but we scored on the first try and spent the following day on an easy ride south to Mulege and the crystalline Bahía Concepción, a beloved spot for kayakers, windsurfers and those who simply want to hang out on a deserted white-sand beach. It’s not uncommon for travelers to abandon their plans and simply plant themselves in this part of Baja, but we didn’t have that luxury. We had to turn around and head north. We retraced our route, with an overnight in El Rosario replacing Cataviña. The return trip wasn’t without drama—one of the KTMs blew a head gasket, puked its oil and coolant and had to be loaded on a truck; and one rider overshot a turn and toured a ditch south of Ensenada, rendering his bike unrideable—but we all made it.

After a few riders peeled off in Ensenada, our diminished group crossed back into the United States at Tecate, a process that took all of five minutes. (Bikes get to weave through waiting cars and go right to the front of the line.) Back in the States, I shook hands with my new friends, my mind on the long slog to Arkansas. It was bittersweet to be back in the land of enforced speed limits and mediocre tacos, and I had a whole lot of Interstate to ride to get home. But I didn’t want to hurry. Call it a Baja state of mind.