by Sherry Jones and Todd Mowbray

photography by Sherry Jones

Rubbernecking with the rest of the crowd at a pair of bald eagles glaring imperiously down from their nest, we were taken aback by the guy who rushed over with camcorder in hand and a face flashing excitement. “Did you see that wolf cross the road carrying a fox?” he gushed. We blinked at him, wondering what the Yellowstone National Park staff had slipped into his cornflakes that morning.

“Right here,” he insisted, pointing to a spot just behind the place where we’d stood, gawking at birds that suddenly seemed common, trivial even. “He just crossed right here with a fox in his mouth.” He shook his head. “I can’t believe you missed it.”

We couldn’t believe it, either. That’s Yellowstone, though: a veritable three-ring safari and special-effects razzle-dazzle where, no matter what you’re taking in, there’s something else you’re missing. Glacier National Park, on the north end of Montana, is the same way. Winding along the Going-to-the-Sun Road, a traveler’s head bobs from side to side like that of a spectator at a Wimbledon match, ogling mountain goats grazing on this hillside, then Bird Woman Falls tumbling graciously down that cliff, then the parade of snowcapped peaks constantly vying to eclipse one another.

Fortunately, we of the TV generation are trained from birth to process this kind of visual bombardment (although three-ring circuses still make me uneasy). On a road trip to Glacier from Yellowstone, at Montana’s southern border, the ability to juggle an array of stimuli comes in particularly handy, because Highway 89—which links the two parks—is a veritable cornucopia of geographic, cultural, visual and social contrasts. If variety is the spice of life, then Highway 89 is a habanero chili.

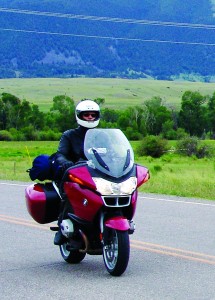

We started our ride, on our brand-spanking-new BMW R12000RT, in West Yellowstone, Montana, a wild-west-style tourist town replete with motels. Arriving at dinnertime, we enjoyed a hearty “Bad Dog” sandwich—smoked sausage smothered with shredded beef brisket—at Beartooth Barbecue. We then cozied up in the sheepherder’s wagon we’d rented for $40 at the Wagon Wheel Inn—a tent, RV and cabin park run by the friendly and very animated Ken Herman.

In the morning we headed into the park, and almost immediately stopped for the aforementioned eagle picture. A few yards later, we stopped again to photograph bison at a distance— these guys have sharp horns and they know how to use them. Then we dodged potholes and gaper blocks on the sometimes rough road while craning our necks at colorful hot pots and steaming fumaroles.

At the Norris Geyser Basin we stopped in hopes of seeing Steamboat Geyser shoot 300-foot jets of hot water, a random event that eluded us. We did, however, see several smaller eruptions during our 10-minute visit. We also strolled to Porcelain Basin, where steam shoots hither and yon from an expanse of mineral-crusted terrain as stark and pale as the moon. Near the park exit we waited out a traffic jam caused by the sighting of a black bear in a tree, and we stopped again at Mammoth Hot Springs, one of Yellowstone Park’s most beautiful features, where about 50 hot springs bubble and drip in pastel terraces of calcium carbonate and limestone.

Gardiner, outside the park’s north entrance, was our lunch stop. This tiny town has an even more touristy feel than West Yellowstone, but we did enjoy the very best pizza ever to grace our lips at the Sawtooth Deli. You don’t have to die to go to paradise in this country. Highway 89 leads out of the park via a huge stone archway built in 1903, then follows the Yellowstone River a few miles north to the 45th Parallel. Park here and follow the trail about half a mile to the hot springs-fed Boiling River, a popular soaking spot where bathing suits are required, but the pools, at least, are au naturel. Imagine our disappointment to find the river closed due to high spring runoff!

There is paradise, however, and there’s Paradise. We urged our bike northward on a mostly straight path with a few wide sweepers to the Paradise Valley, where the massive Absaroka Mountains loom over sagebrush foothills and Chico Hot Springs Resort, about two miles off 89. Popular landscape artist Russell Chatham makes his home here, painting the river bottom as opposed to the big, purple mountains because, he once said, he could never see himself in them. They’re that imposing.

Not everyone is intimidated. Emigrant Peak, looming over the valley at 10,921 feet, is a popular hike with lodgers at Chico wanting to work off some of the calories they consumed in the acclaimed gourmet restaurant. Apres hike, a soak in the lodge’s hot pool or a swim in its Olympic-sized warm pool is de rigueur.

With its horseback rides, day spa, and winter sled-dog rides, Chico caters to a fairly upscale crowd (although rooms can be had for as little as $49), as does the Paradise Valley as a whole, where dude ranches and movie stars have lent a “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” atmosphere to the area. Fly-fishing shops, art galleries and western boutiques adorned with cowboy silhouettes dot the highway all the way into Livingston, not too long ago a windy little cow-town full of hard-drinking working-class characters but now a windy little arts community full of latte-sipping literati.

Not too far down the highway, cowboys come in all three dimensions under a jumble of jagged peaks so haphazard they could only be called “crazy.” The Crazy Mountains tear into the sky a thousand ways as you ride through the Shields River Valley, a lush farming and ranching area fed by a plentitude of creeks and streams, sprinkled with tiny towns and framed by the Crazies to the east and the rugged Bridger Range on the west. While in the Shields, look for posters advertising a concert by the Ringling Five, a popular country band comprising area ranchers singing original songs with silly lyrics such as, “I wear my pantyhose when I’m ridin’.” The mystery of what real cowboys wear under their chaps is thusly solved in a single song.

The highway continues straight north about 75 miles through open farm and range land, with the mountain ranges changing as you near the town of White Sulphur Springs. The Big Belts to the west and the Castle Mountains on the east are older ranges, less feisty but still full of character.

With the weather turning nasty and cold, the dark clouds and blowing rain made for a dramatic ride along the winding, narrow Kings Hill Scenic Byway portion of Highway 89, swooping through numerous tight sweepers climbing and descending through small mountain valleys studded with rock formations—sort of like Monument Valley with vegetation. The highway reaches its pinnacle at 7,400 feet, crossing the Little Belt Mountains before descending in more tight sweepers along Belt Creek.

After cruising on fumes into Belt—wishing we’d gassed up in White Sulphur—we enjoyed a great meal at Indigo in the city of Great Falls, then hopped back onto the bike and drove into the sunset toward the gorgeous Rocky Mountain Front. For about 20 miles Highway 89 takes up four lanes through open, rolling country with a few sweepers to circumnavigate the larger gullies.

At the tiny burg of Fairfield we took a detour to travel Highway 287, a bit closer to the Front and the location of the Viewforth, a bed-and-breakfast inn with a view from the porch of the rocky peaks and cliffs jutting upward from the Plains like so many exclamation points. Built by hand by owners Therese and Keith Blanding, the Viewforth offers a veritable gallery’s worth of contemporary artworks, delectable cooked breakfasts and, for added ambience, a bit of “western music” courtesy of the bleating sheep pastured outside.

Highway 287 continues for 18 more miles alongside the glorious Front, hugging the contours of the land in short, straight sections interspersed with short twisties that climb up and over the numerous hills—up and down and around and around! We converged again with Highway 89 at the tidy, tree-lined ranching town of Choteau. From here the Rockies, ever-present on the west horizon, change from a wall of cliffs to a parade of peaks as you approach the crown jewel of the continent that is Glacier National Park.

This is not an area teeming with Hollywood types, although comedian David Letterman owns property along the Rocky Mountain Front, not far from Choteau. For the most part, this section of the state is much less affluent, and declines into outright poverty in the town of Browning, the administrative center for the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. In Browning, the Museum of the Plains Indian is worth checking out for its display of Indian dress, said to be one of the best in the West.

As beautiful as the scenery has been up to this point, it all falls away like so many cardboard cutouts amid the splendor of Glacier Park. The highway winds among snowcapped alpine peaks so close you feel almost as if you can reach out and touch them, but you don’t dare: You might cut yourself on these cold, sharp edges.

At this point, you’ll find yourself facing a pleasant dilemma: Which to watch, the scenery or the road? For, as the stunning vistas command your attention, so do the almost constant twists as the narrow, two-lane highway ascends into alpine heaven through stand after stand of quaking aspen trees, with their delicate, trembling leaves. Aspen groves, incidentally, are actually a single organism—each tree is a shoot off a single plant, making the species one of the largest single living organisms on the planet.

Stop for lunch at the Park Café, the worst-kept secret in the little gateway town of St. Mary. The café is almost always full, but it’s well worth the wait, if only for the 16 varieties of delicious homemade pie. Then head into the park for a ride on the fittingly named Going-to-the-Sun Road, an engineering marvel carved into the sides of huge, glacier-scoured mountains often compared, and rightly so, to the Swiss Alps.

On the Going-to-the-Sun, you’ll twist and sweep the entire way, but slowly, behind a line of cars and trucks and trailers and, yes, motorcycles steered by folks like you, people who love this planet enough to venture out and place themselves in it. So forget the thrill of the perfectly executed curve for now, and let yourself focus instead on the breath-taking peaks, waterfalls, the wildflowers, the bighorn sheep and, if you’re really lucky, the grizzly bears foraging huckleberries in the alpine meadows of brilliant green.

As in Yellowstone, there’s too much here to see to take it all in at once, even at 25 mph. So relax. Enjoy the sights. There are, after all, no clocks in Paradise. No speedometers, either.

[This article was published in the April 2006 issue of Rider magazine]