(This article A State of MIND: A Lap of Jefferson on a Honda GL1800, was published in the May 2003 issue of Rider magazine.)

It’s sort of Stephen King-ish, really, to wake up one morning and find out the place you’ve been living for years is actually someplace else. A couple of years ago I found out that, in addition to being a resident of southern Oregon, I am also a resident of the mythical state of Jefferson. So I figured I better get out and see what Jefferson is like before I woke up again and found myself living in, say, Oz, or Duluth. I also took the opportunity to get acquainted with a bright yellow GL1800 that Rider had on long-term loan.

Southern Oregon and northern California have always considered themselves separate and distinct, both geographically and culturally, from the rest of their respective states. What began about 150 years ago as simmering resentment over the federal government’s refusal to acknowledge the uniqueness of the area, and to keep the roads in good repair, came to a head in the 1940s, when residents put up roadblocks and toll booths on the major highways passing through Jefferson and threatened to secede from the United States. A couple of days later the Japanese Imperial Navy attacked Pearl Harbor, and Jeffersonians put aside their grievances to throw their energies into the war effort. But World War II only postponed the day of reckoning. Even today, you’ll find not a few people in Jefferson who think severing ties with California and Oregon is a perfectly reasonable idea.

Coos Bay, where I live, would be the only deep-water port in Jefferson, and as such would likely have been the center of Jefferson’s commerce with the Pacific rim. In addition to logs and wood products going out, there would likely be cars, motorcycles, and other goods coming in. It was a slow day at the port the morning I slid the GL1800 out of its moorings and headed south on Highway 101 toward the first stop on my Jefferson tour, a chili cook-off/campout/memorial service in Westport, just north of Fort Bragg.

The first thing I learned about the Wing is its dislike for crosswinds. The near-constant wind howling in off the Pacific is one reason the Oregon—sorry, Jefferson coast is littered with shipwrecks. The stern of the most recent, the New Carissa, remains half-buried in the surf just north of the Coos Bay bar. Efforts to remove it have been foiled not only by nature, but by as tangled a web of bureaucratic red tape as you’ll find anywhere outside the Washington beltway. These days the locals are just about resigned to it becoming a permanent feature of the landscape.

I’ve done the first part of this trip many times, and used it to accustom myself to the Wing’s controls, which quickly became second nature to operate. One that gave me trouble from the start was the indicator on the dash that tells when the trunk lid or a saddlebag lid isn’t secured. The indicator must have been telling me about the lids on some other bike, because each time I checked the ones on mine, they were latched. It took a stout thump on the offending lid with the heel of my hand to make the indicator go out, and after a while I learned not to get on the bike before consulting it.

The Westport event came and went, and I headed back north on 101 to Arcata to catch Highway 299 east. I’d been told 299 was a wonderful road, but in all honesty it isn’t one of Jefferson’s more entertaining thoroughfares. It’s nicely paved—I guess some of that Jeffersonian griping about roads paid off after all—but it left me unimpressed. The most fun I had was bending the Wing onto the long, sweeping turns and marveling at its dead-stable feel. I began to believe that if you peeled off enough of the plastic you’d find a VFR800 under there somewhere. At the very least the big Wing has the soul of a sportbike, though you’d best respect its heft.

At Weaverville I stopped for lunch and to refill my water cooler. The temperature was 101, and I shucked out of the layers I’d put on to ward off the coastal chill. Down to my Darien shell and pants, I stowed the coldweather stuff in the trunk and shut it—and the indicator on the dash said it was open. It kept on saying that as I stood there in the broiling sun, slamming the lid again and again and wracking my brain for ever more colorful profanities. I was on the verge of putting tape over the indicator when it went out. Backing away from the trunk carefully, I got on and rode north on Highway 3, which winds up and through the Trinity Alps and would take me to my night’s rest in Yreka.

The Wings’ wide fairing, a blessing in cold weather, was a curse as the temperature rose with the road. No help at all were the long lines of slow-moving RVs, lumbering along at 35 mph in the no-passing zones and flooring it in the few places where passing was legal. The slower I went the hotter I got, and after a while I decided it was a matter of survival, and pulled the trigger on the Wing’s silky six the next chance I got, double-yellow or no. I felt like a true Jeffersonian as I sailed past the clotted Winnebagos. Ride free or fry!

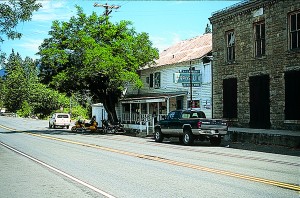

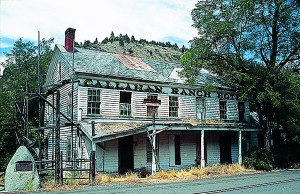

I stopped in Callahan, which was little more than a wide spot in the road with abandoned buildings and one working general store and bar. I asked the woman inside if it was always this hot, and she grinned. “This isn’t hot,” she said. “When it’s really hot, I’ll pin my hair up, and you’ll find me sitting out there—” she pointed to a bench on the porch “—dripping wet with sweat.” I was already sweating like a stevedore, and decided I didn’t need to stick around to see what “really hot” was like.

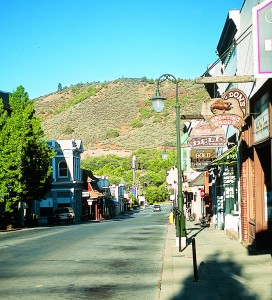

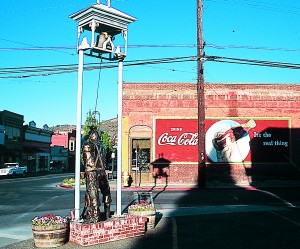

Yreka was at one time nominated to be the capital of Jefferson. I can’t speak for Yrekans, but I think that kind of notoriety would have spoiled a pretty neat little town. Along toward sundown, when the temperature dropped below 80, I took a walk through the center of town along the “15-Minute Drive-In Museum” route that leads past homes built in a dozen different architectural styles, from art deco to Richardsonian Romanesque to classic box. Maybe it’s for the best that Jefferson The Wing was in its element here, almost floating down the wide ribbon of pavement with the cruise control set and the radio tuned to—what else?—Jefferson Public Radio, as the local NPR affiliate calls itself. Shasta loomed ahead, capped in snow despite the rapidly climbing temperatures down at my level. Riding someone else’s big, expensive, astoundingly competent motorcycle straight at a dormant volcano—does it get any better?

At Weed I picked up Highway 97, which cuts through the debris of Shasta’s last snit. The peak loomed in my never got off the ground. A bunch of politicians with capitalbuilding on their minds and the public’s money to spend would only have torn them all down to put up some pompous pile of granite to speechify in.

Although my next day’s destination was Klamath Falls, to the northeast, I got up early enough to beat the heat and rode south on Interstate 5 toward Mount Shasta. mirrors for miles, and I got so used to seeing it there that when it finally disappeared I looked over my shoulder to make sure it was really gone. At a rest stop I met a state worker who remarked how sad it was that I couldn’t have found a more conspicuously colored bike. Against the brick-red background of volcanic rock lining the highway, the Wing was probably visible from space. Agroup of riders on their way to the Concours Owners Group National Rally in Klamath Falls pulled into the rest stop for a breather, and among them was another yellow GL1800. What are the odds of meeting not only another GL1800 out in the middle of nowhere, but another yellow one to boot?

In Klamath Falls I checked into the Red Lion—COG Rally headquarters—and took a shower. I had planned this stop to coincide with the Rally, and arrived on the first day of the five-day event. By the time I came out of my room again there were half a dozen Concours parked nearby. Each time I poked my head out over the next few hours, there were more Connies than before, like a scene from Hitchcock’s The Birds. That night a tent went up and chili was served, roads compared, bikes fixed, and acquaintances renewed.

The next morning began my fifth day on the road, and at breakfast the smell of the barn was stronger than that of the coffee. Earlier I had considered several elaborate routes home, but with the temperatures again predicted to hit triple digits I mapped out the most direct route and hit the road at 7 a.m. The most direct route often disappoints, but not this time. Highway 140 out of Klamath Falls was a delight, first skirting Upper Klamath Lake then diving into thick forests and climbing past broad mountain meadows. The cool, pine-scented air was as good as coffee.

At Medford I picked up I-5. Among motorcyclists, “slabbing it” is a synonym for “boring,” but the stretch of I-5 between Medford and my exit in Winston is one of the most entertaining on the most heavily traveled route through the heart of Jefferson. You can crank it up to 75 and lean back in the deeply bucketed seat only for a few miles before it’s time to bank into a sweeper that rises or dips like a roller coaster laid down through farms and wooded areas. Services are plentiful, but the Wing was feeling more like home than ever, and I didn’t touch a foot to the ground from Klamath Falls to the Winston exit, almost 170 miles.

The final stage of my lap of Jefferson followed a road I know well, Highway 42. I glided through the familiar curves on the now-familiar Wing, and capped off the day with a caffeine stop at the Caboose Lady Coffee Shop, where you can find me most afternoons when I’m not exploring mythical states. No matter if you call it Oregon or Jefferson, home is a good place to be.